|

||

|

|

|||||

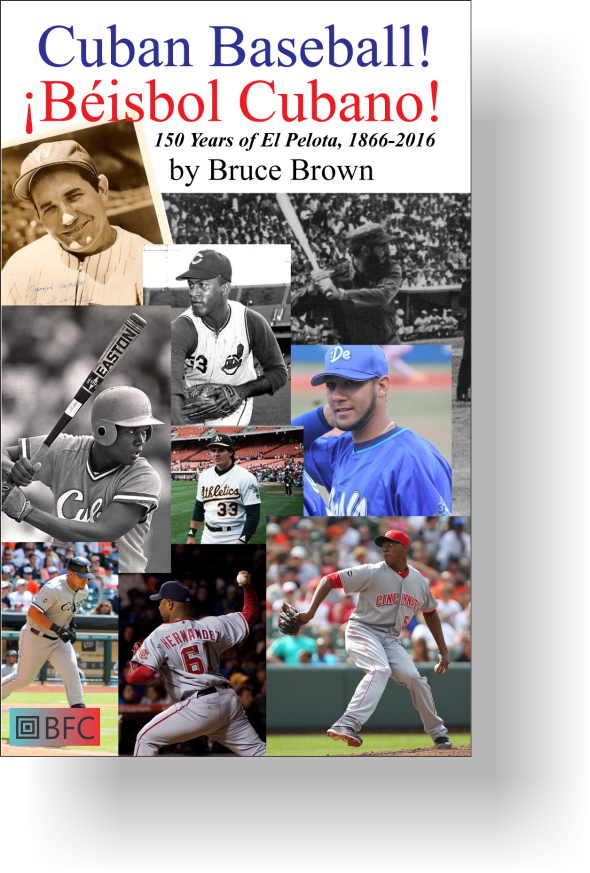

Quick Take -- Ground-breaking Cuban baseball writer Bruce Brown serves up the full sweep of Cuba's glorious baseball tradition, history and achievement in Cuban Baseball! / ¡Béisbol Cubano! -- from the beginning at Palmar del Junco in 1866 to the Communist scouted, trained and nurtured Cuban béisbolistas who are reshaping Major League Baseball in Capitalist American today. Excerpt --¡Béisbol Cubano!THE JOKE that flying baseballs are the greatest pedestrian hazard in Havana is only partly a joke.

Passionate discussion of el pelota (which means simply "the ball") is an afternoon staple of establishments like El Pelota Cafe on Havana's 23rd Street, and in the evening the fanaticos gather at Havana's 55,000-seat Estadio Latinoamericano to drink thimbles of sweet Cuban coffee and watch the game. Here, on a well-kept natural-grass field with brick-red base paths, Cuban players compete in the top two levels of Cuba's rigorous competition year round, with the National Series scheduled during the prime winter months and the less successful Selective Series scheduled during the climatologically challenged summer months. Out of these competitions comes the Cuban National Team, the apex of Cuban baseball and one of the most successful athletic organizations in modern history. For decades, Cuba has dominated world amateur baseball in somewhat the way Taiwan has dominated world Little League baseball and the United States has dominated world professional baseball. The Cuban National Team has won 50 Gold Medals for baseball in international competition since 1961, including 25 in the World Cup of Baseball, 12 in the Pan American Games and three in the Olympics. These triumphs have been particularly gratifying for the government of Fidel Castro, which has made success in baseball a major priority.

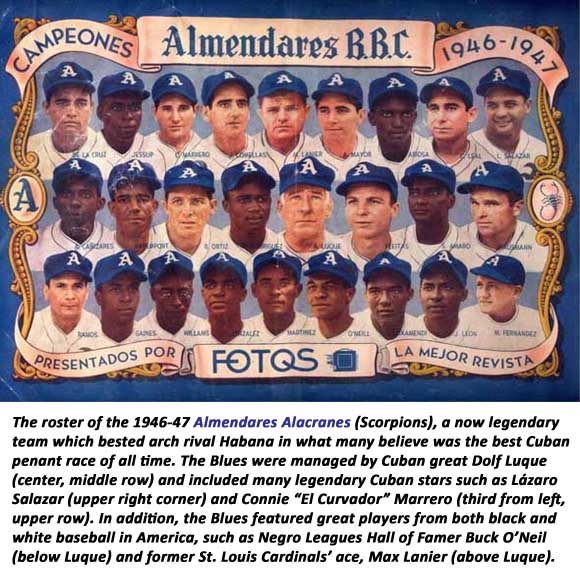

Historically, the biggest difference between Cuban baseball and American baseball has been the racial attitudes of the two. The professional Cuban League was integrated in 1900 -- nearly a half century before professional baseball in America -- with the admission of a team from San Francisco which was all black. When San Francisco easily won the Cuban League pennant that year, most of the remaining teams began bidding for black talent to add to their squads. After that, blacks and whites competed freely in professional baseball in Cuba. So when American baseball was a bastion of racism, the greatest interracial games -- pitting Ty Cobb against John Henry Lloyd, and Carl Hubbell against Luis Tiant, Sr., etc. -- took place in Havana's Almendares Park, not in New York's Yankee Stadium or Boston's Fenway Park. It was the Cubans who proved that the game could be successfully integrated, and it was the Cubans who provided the Brooklyn Dodgers the facilities where they could bring Jackie Robinson to spring training in 1947.

Americans chronically complain that the Cuban National Team is really a professional squad in amateur disguise, but that's because Americans don't understand the differences between Cuban and American culture. Cuba has always had a much stronger non-scholastic amateur sports tradition than the United States, especially in baseball. For instance, "El Curvador" Connie Marrero spent most of his career playing high level amateur ball in Havana, and only turned pro and went to the Washington Senators at the end of his playing days in 1950. In fact, the Cuban Federation of Sport or Federación Cubano de Atletismo, which oversees all Cuban amateur sports, dates to 1924, nearly three decades before the Revolution. Today in Cuba, high level athletes play the sport they love on "sports leave" from their regular jobs, and during the baseball season ballplayers are paid at the same rate they get from their off-season work. Cuban baseball players may receive performance bonuses, but many Cuban stars still make only a few thousand dollars a year. Liván Hernández said he made $6 a month in Cuba pitching for the Villa Clara Naranjas in the Cuban Selective Series (where he led the league in strike outs in 1994). When he came to the United States in 1995, he reportedly signed a $4.6 million dollar deal with the Florida Marlins. |

|

Americans tend to see this arrangement as outrageously exploitive -- perhaps even tantamount to slave labor -- but Pelota Revolucionaria has many virtues that Americans also tend to overlook. First of all, Pelota Revolucionaria produces superior baseball players. On that point, there is no debate. Cuban baseball players are both very well conditioned and very well trained. In fact, some aspects of baseball training in Cuba may be better than anything in the United States. For instance, Cuban-trained pitcher Aroldis Chapman is generally considered the hardest thrower in baseball today, and a kinematic analysis of Cuban pitchers' windups reveals that this may be partly due to the way Cuban pitchers are trained to throw (more on this later). Second, all baseball games in Cuba are free. That bears repeating: all baseball games in Cuba are free. And there aren't any $12 beers and $50 parking fees either! In Cuba, baseball isn't a "privilege" of the privileged classes. It's a basic right. Imagine being able to walk into Yankee Stadium or Chavez Ravine without paying anybody or anything, just because you felt like watching the Yankees or the Dodgers play! In Cuba, this is the reality that accompanies comparatively low player salary levels, and the result is that it enriches the culture as a whole, not just a few profiteering athletes and their corporate overlords. The idea in Communist Cuba is not to create a massive divide between wealth and poverty like in the United States; the idea is to make the wealth of the country available to as many as possible.

Another conscious policy decision since the Revolution by Cuba's Communist government has been to spread high level baseball play all through the island, rather than concentrate it in Havana, Santiago de Cuba and the main municipal areas where the most money can be made from the teams' operation. So today even relatively remote Guantanamo on the far, east end of the island has a Serie Nacional team, the Guantánamo Indios, and a nice stadium in to play in, Nguyen Van Troi Stadium, a 14,000 seat facility named for a Viet Cong hero of the Viet Nam War. In the old days of professional baseball in Cuba before the Revolution, there were at most half a dozen teams in the Cuban League. Today, under Pelota Revolucionaria there are currently 16 teams in the Cuban National Series alone.

In response to some Cuban baseball players' desire to compete against the highest levels of professional play, the Cuban government has allowed a few high-level Cuban peloteros to sign contracts with teams in the Nippon Professional League, the major leagues of Japanese baseball. Cuban superstars Orestes Kindelán, Omar Linares and Antonio Pacheco were among the first to try playing in Japan, and Yulieski Gourriel, a star third baseman for the Sancti Spiritus Gallos in the Cuban Serie Nacional and the son of Pelota Revolucionaria great Lourdes Gourriel, played for the Yokohama DeNA BayStars in the Japan Central League in 2014, when he hit .304 with an .884 OPS in his rookie season in Japan. Arranging for Cuban stars to play in Japanese professional baseball was a shrewd move by both the Cubans and the Japanese, but it hardly addressed the root of the Cubans' problem with American baseball and the Almighty Dollar. In 2014, when Cuban star Yulieski Gourriel played in Japan, there were 25 Cuban stars playing in the major leagues in United States, including American League Rookie of the Year José Abreu. And 2015 is slated to be the biggest year for Cuban baseball defectors to America ever, including some highly touted prospects who are still in their teens like Yoan Moncada.

The difference between a player coming from, say, Japan's Nippon Professional Baseball to Major League Baseball in America is that major league teams have to bid for the right to negotiate with Japanese players, with the bid money going to the team that has the player, as was famously the case in 2011 when the Texas Rangers paid $51.7 million to the Nippon Ham Fighters in Japan's Pacific League for the mere opportunity to negotiate a deal with the Ham Fighters' ace pitcher Yu Darvish. In the case of Cuba, however, American major league teams pay nothing to the foreign league for the highly developed players they sign. That's zero dollars versus $50 million for negotiating rights per premier player. Although you NEVER see it mentioned in the American sports press, part of what makes Cuban ballplayers attractive in America right now is that American baseball teams don't have to pay a posting fee for them! This is the eight hundred pound gorilla sitting unnoticed in the middle of the room when it comes to American major league teams signing Cuban players.

But as my mother used to say, "it's an ill wind that blows no good." The happy result of all this unhappiness is that Cuban baseball talent is fanning out across the world like never before -- so that fanaticos everywhere can see the intelligent, high intensity Latin style that the Cubans have brought to the game from the very beginning of baseball, almost 150 years ago. Cuban fanaticos especial love players who are explosivo, or explosive, and you can see this quality in the Cubans, generation after generation... This is an excerpt from Cuban Baseball! / ¡Béisbol Cubano! by Bruce Brown. Buy Bruce Brown's new book on Amazon! ©Copyright 1984, 2015 by Bruce Brown |

|

© Copyright 1973 - 2020 by Bruce Brown and BF Communications Inc. Astonisher and Astonisher.com are trademarks of BF Communications Inc. BF Communications Inc. Website by Running Dog |

|