|

|||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Charles Windolph's Story of the Battle

SERGEANT CHARLES WINDOLPH'S ACCOUNT Chapter 7 I'LL NEVER FORGET that first glimpse I had of the hilltop. Here were a little group of men in blue, forming a skirmish line, while their beaten comrades, disorganized and terror stricken, were making their way on foot and on horseback up the narrow coulee that led from the river, 150 feet below. We recognized Major Reno and Lieutenant Varnum. I believe both of them had lost their hats and now had handkerchiefs tied around their heads to protect them from the blazing Montana sun. I saw Lieutenant Varnum reach up and shake hands with Lieutenant Godfrey of "K" troop, who was Varnum's regular company commander. And I heard him say something about a hard fight and that they'd got a damn good licking. It's no use pretending that the men here on the hill, from Reno down, were not disorganized and downright frightened. They'd had a lot of men killed, and it had only been the grace of God, and the bad aim of the Indians, that had let them escape across the river with their lives. But it wasn't at all certain that they could keep them now. For there were hundreds of Indians still down there in the valley, maybe a half mile from where we were standing. They were still firing at stragglers trying to cross the river and reach the little command here on the hilltop. Cool, capable Benteen more or less assumed command. Major Reno had just come through a terrible experience, and at the moment was glad to have Benteen, his junior, take over. Quickly Benteen dismounted his own three troops and ordered us to form a skirmish line. Reno's men had expended most of their ammunition so we were told to divide ours with them. We had Benteen's 120 men intact and there were around sixty men who'd been in the valley fight with Reno. And even before we got the kinks out of our legs from our long hours in the saddle, we were asking one another, "Where's Custer?" Officers and men alike were trying to solve the riddle. What had become of Custer and his five troops? We knew from Trumpeter Martini who'd come back with that last message for Benteen to hurry forward with the packs, that Custer had ridden northward over these rolling hills to the east of the Little Big Horn. Some of Reno's men told in excited tones how from the valley below they had seen Captain Yates' white horse troop on a bluff on our side of the river, maybe a mile or so down the river, to the north. Others said they had seen Custer and one or two men looking down from a hilltop. Trumpeter Martini figured it was maybe a mile on farther downstream, to the northward from our hill, to the spot where he'd been ordered to report to Benteen. Apparently Custer was now much farther on to the northward and was this moment hotly engaged. But no one was certain. All we knew was that he had disappeared with almost half the regiment. And luckily for unhappy Reno, we had come up just in time to save him from what might have been complete destruction. We could see the river valley down below from where we were spread out in a circular skirmish line here on Reno Hill. Some of the poor troopers were still being cut down by the swirling mass of Indians. There was shooting, and dust, and savage yells -- then suddenly most of the Indians began galloping downstream. That's to the north, and before long we could hear heavy firing from down that way. Reno and Benteen and two or three of the officers held a little conference, and we saw Lieutenant Hare, who had had charge of Reno's Indian scouts, suddenly mount Godfrey's horse and head back down our trail to the southward. Maybe it was fifteen or twenty minutes, or possibly a half hour, before he came up at a trot with several pack mules, loaded with ammunition boxes. The rest of the dozen ammunition mules slowly dribbled in, and before long the pack train itself came up. We now had 24,000 rounds of rifle ammunition, food and a new force of not less than 130 armed men. Except for an odd hostile shot, fired from a distance, there was no firing near us now. The Indians apparently had left for the north. We could hear the sound of distant firing echoing down through the hills and valleys from that direction. Custer must be down there. -- 2 -- It was now maybe 4:30 and the sun was still fairly high in the sky. We troopers didn't know what was going on, but I remember that Captain Weir suddenly rode off to the north alone, and a minute later, Lieutenant Edgerly, second in command of "D," followed with the whole troop. The pack mules were coming up about this time and there was a lot of speculating going on. As I recall, Reno had seven wounded men, some of them in pretty bad shape. But altogether he now had around 310 effective, which was a little more than half the total number in the regiment. Custer had around 220 men with him. It's pretty hard to estimate time under such circumstances, but as I've tried to reconstruct the situation over the years, I believe it must have been around 5 o'clock when Reno and Benteen ordered the whole outfit to move northward, in the general direction Captain Weir and his troop "D" had taken a good half hour before. The wounded men who could mount were put on horses, but the others were carried in blankets by details of six troopers on foot. It was slow and painful work, and I've always figured that most of the officers thought it was a questionable move. We'd gone less than a mile when we got in sight of Weir's troop. Way off to the north you could see what looked to be groups of mounted Indians. There was plenty of firing going on. Pretty soon it looked as if the Indian masses were coming towards us. It didn't take long to realize that this was true. Here we were stretched out all over the hell's half acre, a troop on this hill knob, another in this little valley and over there a third troop. Behind, at a slow walk, came the pack trains, the wounded men and the rear guard. Reno and Benteen both sensed the danger and ordered a withdrawal. The advance troops were dismounted and fought as skirmishers. Soon the Indians were pressing hard, and it was only good luck and the hard courage of Lieutenant Godfrey's troop, fighting stubbornly on foot, that kept disaster from overtaking us. We were able to regain Reno's Hill while Troop "K" kept back the Indians until the men, retreating slowly, got close, enough to the hilltop to make a dash for it. It was now possibly 6:30 in the afternoon, with three hours of daylight still to go. Hurriedly Reno, with Benteen helping him with advice and suggestions, posted his forces for the coming attack. In the center in a slight depression the horses and mules were staked out, and an inadequate little field hospital was established. But it was impossible to shield the men and stock from the Indians firing from a hilltop off to the east. Animal after animal was killed, and men were hit. It was tough not to be able to do something about it. My own Troop "H" was posted to the south, in a dangerous position, bordering the river. There was higher ground behind us and we were as helpless as the animals and wounded men to protect ourselves from fire. But we were not yet fully aware of our peril as we hurriedly piled up such inadequate barricades as we could find. We used pack saddles, boxes of hard tack, and bacon, anything we could lay our hands on. For the most part it wasn't any real protection at all, but it made you feel a lot safer. We'd hardly got settled down on our skirmish line, with "H" men posted at twenty-feet intervals, when the Indians had us all but completely surrounded, and the fighting began in earnest. There was no full-fledged charge, but little groups of Indians would creep up as close as they could get, and from behind bushes or little knolls open fire. They'd practice all kinds of cute tricks to draw our fire. Maybe a naked redskin would suddenly jump to his feet, and while you drew a bead on him he'd throw himself to the ground. Then they'd show a blanket or a headdress and we'd blaze away, until we learned better. I always figured if the Indians had used their heads and made a charge on us from all directions at the same 'time, they could have swept over us. But they didn't. An Indian's way of fighting was tp follow his own devices. If he could "count coup" on an enemy with his long "coup stick" he was even prouder than if he killed a man. One Indian ran in close to our lines to touch one of our dead men with his "coup stick," and we filled him full of lead before he could get away. At that time the Indians were pressing "H" hard, and we were in grave danger of being overrun. -- 3 -- The sun went down that night like a ball of fire. Pretty soon the quick Montana twilight settled down on us, and then came the chill of the high plains. There was no moon, and no one ever welcomed darkness more than we did. The firing had gradually died out. Now and again you'd hear the ping of a rifle bullet, but by 10 o'clock even that had stopped. But welcome as the darkness was, it brought a penetrating feeling of fear and uncertainty of what tomorrow might bring. We felt terribly alone on that dangerous hilltop. We were a million miles from nowhere. And death was all around us. Across the river and down below in the valley of the Little Horn, where so many of our men lay dead, we could see great fires and hear the steady rhythm of Indian tom toms beating for their wild victory dances. The Indians apparently must have had great success everywhere this Sabbath day. But now and again you'd hear what sounded like the high-pitched wailing of the squaws, crying to the Great Spirits for their departed dead. All through the short, black night the orgy went on down below in the river valley. It struck fear in our hearts, just as the mystery bf Custer's disappearance made our blood run cold each time we tried to solve it. Where was Custer? What had happened to him? Surely he must have met with some sort of defeat and then had ridden on downstream towards the junction of the Little and the Big Horn. Gibbon's column, with General Terry, would be arriving there soon. Had Custer reached there, with such of his five troops. as had escaped the fighting that had occurred three miles on to the north from where we were lying? They could not all be killed. Not Lucky Custer, and those five gallant troops who rode with him. Why had he abandoned us? In those three bloody hours before darkness had saved us, we had had no less than a dozen men killed and three times that number wounded. You could hear them crying out for water all through the short night. It would be death to try to reach the river, even in the covering darkness. We had been busy too, digging shallow holes with our mess kits, our steel knives and forks and with our fingers. We would not have to face the daylight without at least some little protection. It was pitifully inadequate but it was something. Off to the east pink and yellow light began to show. Dawn was breaking. Two shots sounded from the hilltop behind us. Soon there was firing all around. -- 4 -- It had rained a little during the night and some of us had taken our overcoats from the cantles of our McClelland saddles and put them on. It was cold here on this bleak hilltop, too, and those old army bluecoats felt good. My buddy, a young fellow named Jones, who hailed from Milwaukee, was lying alongside of me. Together we had scooped out a wide shallow trench and piled up the dirt to make a little breastwork in front of us. It was plumb light now and sharpshooters on the knob of a hill south of us and maybe a thousand yards away, were taking pot shots at us. Jones said something about taking off his overcoat, and he started to roll on his side so that he could get his arms and shoulders out, without exposing himself to fire. Suddenly I heard him cry out. He had been shot straight through the heart. The lead kept spitting around where I lay. Up on the hilltop I could see a figure firing at me from a prone position. Looked like he was resting his long-range rifle on a bleached buffalo head. I tried my best to reach him with my Springfield carbine but it simply wouldn't carry that far. A few minutes after Jones was killed, a bullet ricocheted from the hard ground and tore into my clothing. About this time the surgeon came up and took a look at Jones. He asked me if I wasn't wounded. I said no, that I was all right. "Put your hand inside your shirt," he ordered. I did, and when I pulled it out it was bloody. That ricocheted bullet had given me a slight flesh wound. The surgeon wanted to bind it up but I told him there were plenty of badly wounded men to take care of. A minute or two later another bullet from the hilltop tore into the hickory butt of my rifle, splitting it squarely in two. I was plenty mad because my army carbine wouldn't let me return the compliment. Somehow I always figured that the sharpshooter who had killed Jones, hit me and split my rifle butt, must have been either a renegade white man, or a squaw man of some kind or another. He could shoot too well to have been a full-blood Indian. [Note: actually, the marksman who killed Pvt. Jones was probably Oglala Sioux warrior White Cow Bull.] Along about this time our thirty or forty wounded men began crying out again for water. "H" troop held the hill here on the southwest. There was a draw that ran down the west side of the hill to the river. It was rough and exposed and it looked like a dead cinch that any one who tried to work his way down that draw to the river would be killed. Indians concealed in bushes across the river were firing up at us, and they had every foot of this draw and the river bank covered. But we had to do something for those men who were wounded and crying for water.

But lots of times the men who most deserve the medals don't get them, because no officer happened to see their deed of valor or, if he did see it, failed to turn in a recommendation for a decoration. Fact is that many men that day deserved the highest of decorations for their bravery. There was Sergeant Paul, for instance, who led the charge we made a little later. And there were "Crazy Jim" Seivers and Dan Newell, and Slaper and others. I got more than my share of credit that day. After we'd got the water up for the wounded, Benteen told me he was making me a Sergeant-promoting me on the field of battle. I was always proud of that. Speaking about that charge we made; sometime that morning the Indians were crowding us pretty hard. "H" was the most exposed of any of the troops, and it looked as if the hostiles were massing for a sudden charge. Benteen had been walking up and down the line urging the men to hold fast, not to waste their fire, and to keep cool. I remember saying to him: "Colonel, you better get down, sir, or you'll get killed." "Don't worry about me," he answered grimly. "I'm all right." He sure had a charmed life that day. But things looked bad, and finally Benteen hurried to the north side of the lines and asked Major Reno for reinforcements. He made it clear that the Indians were about to charge his line, and that if they were able to sweep over it the whole outfit would be destroyed. Reno told him to take as much of "M" troop as he could gather. Those men certainly looked good to us. Soon after they came up Captain Benteen led the charge. Yelling and firing, we went at the "double quick" and the Indians broke and ran. When we had cleaned them out for a hundred yards ahead of us, we hustled back to our holes. Once again we settled back to the business of getting fired at, with men hit at intervals, and with the poor horses and mules taking a terrible beating in their hollow. It must have been along about this time that Benteen called me to attention and made me a Sergeant. We'd had one sergeant and two men killed and twelve wounded, in "H" troop alone. I suppose it was early in the afternoon when the firing seemed to quiet down. Now and again bullets would come tearing in, but gradually they became fewer and fewer. Then below across the Little Horn heavy smoke began drifting southward. Pretty soon it became clear that the Indians were firing the grass. That seemed odd, unless they were getting ready to leave. The gunfire had almost ceased and some of us left our trenches and stood in little groups on the brow of the hill. Then something happened that I'll never forget, if I live to be a hundred. The heavy smoke seemed to lift for a few moments, and there in the valley below we caught glimpses of thousands of Indians on foot and horseback, with their pony herds and travois, dogs and pack animals, and all the trappings of a great camp, slowly moving southward. It was like some Biblical exodus; the Israelites moving into Egypt; a mighty tribe on the march. We thought at first that it must be some trick: that the Indians were only removing their families from danger and that the warriors would soon return and try to overwhelm us. Patiently we waited in our little trenches. The long June afternoon dragged on. The firing had all but ceased. The smoke in the valley had blown away, and the last Indian had gone. While guards kept their posts, the rest of the men led such horses as were not killed down the steep draws to the river. It was the first drink they had had since early after noon the day before. Gently we buried our dead in the shallow trenches we had dug for the living. Then Reno ordered the whole camp to move as close to the river as possible. We would get as far away as we could from the terrible stench. There was plenty of water now for the wounded. And towards evening the company cooks made us the best meal they could. At least we had hot coffee and plenty of bacon and soaked hardtack. It was our first meal in thirty-six hours. Then night came down. We were weary, but while those on guard were awake and alert, the rest of the command slept. But it was an uneasy sleep. We still had heard no word from Custer. We began to suspicion that some terrible fate might have overtaken him. What it was we could only guess. I Fought With Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolf, Last Survivor of the Little Big Horn, as told to Frazier and Robert Hunt, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1947 p. 96 - 107

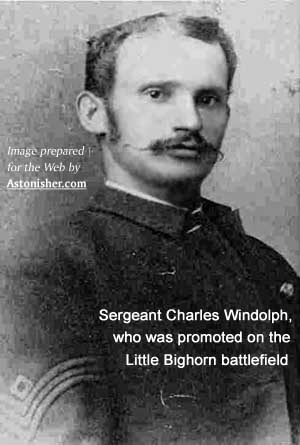

Charles Windolph (sometimes spelled Windolf, especially in later years) was promoted to Sergeant on the Little Bighorn battlefield by Capt. Frederick Benteen, and was subsequently award the Medal of Honor for his valor at the Siege of the Greasy Grass. When this memoir appeared in 1947, he was billed as the last living member of the Seventh Cavalry who fought at the Little Bighorn, so in a way you could say he got the "last word" on the subject. Here is another chapter from Windolf's book, I Fought With Custer. |

|||||||

Where was

Where was  Finally Captain Benteen called for volunteers. I think there were seventeen of us altogether who stepped forward. He detailed four of us from "H" who were extra good marksmen to take up an exposed position on the brow of the hill, facing the river. We were to stand up and not only draw the fire of the Indians below, but we were to pump as much lead as we could into the bushes where the Indians were hiding, while the water party hurried down to the draw, got their buckets and pots and canteens filled, and then made their way back. It just happened that the four of us who were posted on the hill were all German boys: Geiger, Meckling, Voit and myself. None of us four were wounded, although we stood exposed on that ridge for more than twenty minutes, and they threw plenty of lead at us. Several of the water party, however, were badly wounded, although we kept up a steady fire into the bushes where the Indians were hiding. Each of us was given a Congressional Medal of Honor.

Finally Captain Benteen called for volunteers. I think there were seventeen of us altogether who stepped forward. He detailed four of us from "H" who were extra good marksmen to take up an exposed position on the brow of the hill, facing the river. We were to stand up and not only draw the fire of the Indians below, but we were to pump as much lead as we could into the bushes where the Indians were hiding, while the water party hurried down to the draw, got their buckets and pots and canteens filled, and then made their way back. It just happened that the four of us who were posted on the hill were all German boys: Geiger, Meckling, Voit and myself. None of us four were wounded, although we stood exposed on that ridge for more than twenty minutes, and they threw plenty of lead at us. Several of the water party, however, were badly wounded, although we kept up a steady fire into the bushes where the Indians were hiding. Each of us was given a Congressional Medal of Honor.