Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Peter Thompson's Story of

PETER THOMPSON'S ACCOUNT ON THE FOURTH day of May 1876, we moved out of our quarters and passed in review, marching around the post and thence towards our first camping-place three miles below Fort Lincoln. We, marched in the following order; cavalry first, artillery next, infantry next, the wagon train bringing up the rear. All the companies of the 7th Cavalry converged at this point. While lying in camp here, we learned that the expedition formed, was against a large body of Indians who had left their different reservations stirred up and.led by a turbulent warrior chief named Sitting Bull and other dissatisfied chiefs and squaw men? Our regiment was composed of twelve companies, about seventy men and officers composing a company. There were three Majors, each commanding four companies. One colonel commanding the whole regiment. We were short two majors, several captains and lieutenants, the majors on sick leave namely Majors Tilford and Merrill, the captains and lieutenants being on staff and other duties distant from this field of action. It is hardly possible to get the full strength of a regiment into the field as there is always some one on the sick list and others on detached service, and ours was no exception to the rule. |

|||||||||

On the 15th of May orders were given us to move to the Hart River where we would meet the paymaster and receive our wages and all stragglers not going with the expedition would be cut off. But Oh! We here General Terry had joined us at Fort Lincoln, hence the expedition was under his command. Terry was a gentleman in every respect, he exercised very little of his authority on the march but let Gen. Custer have charge o f it. During the earlier part of the expedition, it rained quite often making the advance of the wagon-train slow and tedious. The train was composed of about one hundred and sixty wagons, twenty of which belonged to citizens and some of their stock became so weak that it was all they could do to haul their empty wagons. When we came to a long hill, a muddy place, or a ford we had to get ropes and help them out of their difficulty. What a nuisance they were! A government team consisted of six powerful mules to each wagon and they very seldom got into a place out of which they could not pull. There were places where we had to build bridges and grade approaches before we could get across, a work which ought to have been done by each company in turn. But this was not the case. The captain of our company, Tom Custer, was on his brother's staff. Lieutenant Calhoun was in command of Company E and this left Lieutenant Harrington in command of our company. He had us at nearly every bridge-building or road grading until we began to grumble and in no undertone either. Our dissatisfaction became so pronounced that one day Major Reno overheard us. The next time our company was brought up by Harrington, Major Reno ordered us to the rear. Were we sorry? Not much. As we travelled over the trackless prairie, we came across the trail made by Stanley when in conjunction with Custer in 1873, he drove the Sioux across the Yellowstone River." We followed this trail until we came to the Little Missouri River where we camped some time for the purpose of constructing a crossing over the river and scouting up the river. Major Reno being the only officer of that rank in the expedition while on the march was in command of the right wing, and Capt. Benteen who was senior captain was in charge of the left wing. Each wing camped in separate but paralled lines. It was about the 20th of May that we came to the Little Missouri River. While here Custer took Company C up the river to look for signs of Indians. We passed over a very rough country and were compelled on that account to cross the river many times, making it very hard on our horses. They had to clamber up the slippery banks and on recrossing to slide down into the river with their legs braced. The distance we travelled was 22 miles, the only sign of Indians we saw was a camp some months old. So we retraced our weary way and arrived in camp late at night with our horses completely tired out. We had along with our expedition two companies of Infantry and while crossing streams they would climb onto the wagons like bees on a hive. The poor fellows had a hard time of it when the days were hot or when it rained. General Terry suggested to Capt. Sangers of one of the infantry companies that when the ground was favorable he should allow his men to ride on the wagons. Capt. Sangers replied that his men could walk thirty miles a day and run down an antelope at night. But we all noticed that he clung close to his saddle during the march. It was all nice enough for the captain of infantry on horse-back with his men following behind him to speak thus. All the soldiers would have liked to have seen him on foot after making such a remark. The first day's march after leaving the river was very disagreeable; for it rained all day. On the 22nd of May, we came in sight of the Bad Lands which at a distance presented a curious and pretty appearance. Some parts of them looked fiery red, others dark brown and black. What brought about this freak of nature, I cannot tell. There has been much speculation about it by travellers; some think that it was underlaid by a bed of coal, which in some way caught fire, burning, upheaving, and throwing the surface into all manner of shapes, but others think that it is of volcanic formation. Roads there were none and where water was found it was very bad on account of the alkalie it contained. We were two days constructing a road for the passage of the wagons. While the rest of the regiment were busily engaged constructing the road, a company of infantry, for the country was almost impassible to horses, was deployed on both sides of us as skirmishers. We were very glad when we reached the open prairie. Timber is seldom seen in this country; a few cottonwoods along the streams and red pine on the bluffs being all there is and sometimes not even in these places was wood to be found. The first camping place after leaving the Bad-Lands found us without wood, but by dint of hard rustling and breaking up extra wagon tongues and such other odds and ends as we could find we managed to warm some coffee and cook some salt meat. As we approached the Powder River, the country began to be very rough and broken. When about 15 miles from the river, Gen. Custer took half of our company and dashed towards it." His object was to find as easy and direct route as possible. We rode in this mad way for nearly an hour when we came to a halt. Riding up to one of our corporals name French, Custer told him to take a man and ride in a certain direction where he would find a spring of water and ascertain what condition it was in. Custer then wheeled his horse around and dashed away in a westerly direction, leaving us standing at our horses' heads until his return. Custer's brother Tom was the only one who went with him. This action would have seemed strange to us had it not been almost a daily occurance. It seemed that the man was so full of nervous energy that it was impossible for him to move along patiently. Sometimes he was far in advance of all others, then back to his command; then he would dash off again followed by his orderly named Bishop, who tried in vain to keep Custer in sight. He would either return to us again or seek an elevation where he could catch a glimpse of the general dashing ahead over the country and try to intercept him on his way back. General Custer had two thoroughbred horses, one a sorrel and one a dark brown, and no common government plug had any show whatever to keep up with him when he was riding full speed. He also had a number of grey-hounds for hunting purposes and many a chase he and his brother had when on this march. But after we crossed the Powder River, hunting ceased. Corporal French soon returned looking very foolish. General Custer rode up to him and said "Did you find the spring?" "No, sir," said French. "There is no spring there." "You are a liar," said Custer. "If you had gone where I told you, you would have found it." He spoke in such a positive manner that we felt sorry for poor Corporal French, for Custer knew the country well, even better than the scouts, who were hired by the government to guide the expedition. We had two scouts, along with us, one named Charley Reynolds, a quiet and dignified man. He led the wagon train, piloting it and avoiding all bad places; a better scout for a white man would be hard to find, his mount was invariably a grey mule. The other one was a half breed named Mich Burey [Note: probably Mitch Bouyer] who was well informed regarding the country. He had crossed this part of the country before, hiding during the day-time and traveling at night for fear o f the Sioux who were jealous of all strangers. With the expedition also were twenty-four Scouts, a dirtier set of rascals would be difficult to find. Their interpreter was a half breed named Frank Gerard, and their chief guide was Billy Jackson also of Indian extraction." But of these we will have more to say by and by. But to come back to the story, while we were waiting and speculating as to our next move, Lieutenant Cook. adjutant of the 7th Cavalry and a member of Custer's staff, rode up and said that it was General Terry's desire that we should go into camp and not attempt too long a march. So we went back and f ound the regiment in its camping place for the night. On the following day we continued our march and arrived at Powder River early in the forenoon. Immediately a scouting party was formed composed of the six companies B, C, E, F, G, and L, which was all of the right wing. These were commanded by Major Reno. Each company was provided with a sufficient number of mules to carry the necessary provisions and ammunition. I do not think that there were half a dozen men in the scouting party who knew how to pack a mule without having its load work loose. But fortunately there were five citizens along with us who knew the business and the boys soon learned to lash a pack saddle and load securely. After two days of preparation, this scouting party started off in a northwesterly direction. The only wheeled affair we had was a large Gatling gun drawn by four horses. Originally reprinted in The Black Hills Trails, by Jesse Brown and A.M. Willard, Rapid City Journal Co., Rapid City, SD, 1924

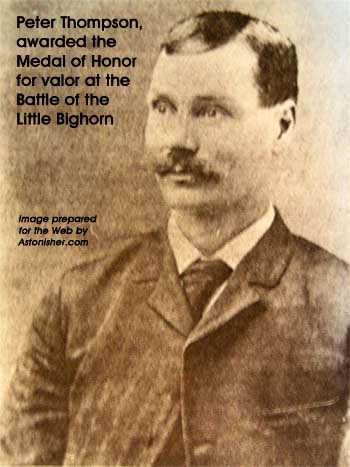

This section of Peter Thompson's account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where he received the Medal of Honor, deals with Custer's march through the Powder River country en route to the Little Bighorn. Thompson's account is one of the two Lost Texts of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and he has largely been written out of the history of the battle by American writers. * * * Special thanks to polfdesign.com for finding the excellent historical photo of Peter Thompson and providing this additional biographical information: "Peter Thompson, born December 28, 1854. Fifeshire, Scotland. Emigrated to the United States 1865, settled with his parents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylyania. Enlisted in the United States Army for 5 years, September 1875. Upon enlistment was assigned to Jefferson Barracks, St . Louis, MS. Transferred October 1875, Stationed at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory. Assigned to Co. C, 7th Cavalry, under Capt. Tom Custer, 1st Lieut. Calhoun and 2nd Lieut. Harrington." After the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Thompson "participated in the Northern Cheyenne Campaigh 1878 Honorable Discharge 1880 Homesteaded Alzada, Montana 1890 Married September 21 1904 to Ruth Boicourt, two children, Susan and Peter Jr. Authored the narrative, "Custer's Last Fight, The Experience of a Private in the Custer Massacre" Died December 3, 1928, Veterans Home, Hot Springs, SD, buried at Lead, SD." -- B.B. |

|||||||||