|

||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Henry Rowan Lemly's Story of the Battle

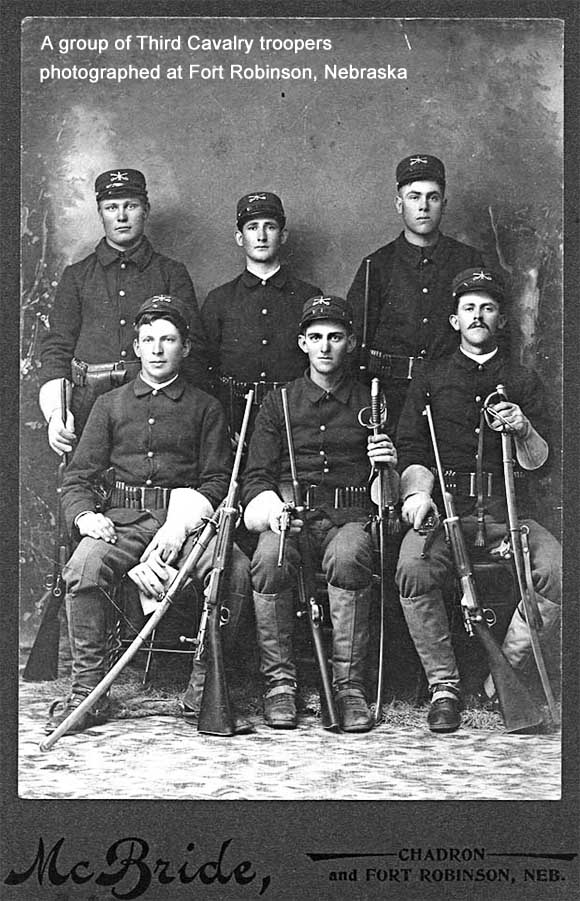

FIGHTING THE INDIANS By Lt. Henry Rowan Lemly Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition, ON THE MORNING of the 16th inst., this entire command under Brigadier General Crook, comprising fifteen companies of cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel Royall, Third Cavalry, to-wit: ten companies of the Third Cavalry, commanded by Major Evans, the separate battalions thereof consisting of five companies each under Captain Mills and Henry, respectively, and five companies of the Second Cavalry under Captain Noyes; five companies of the Fourth and Ninth Infantry, commanded by Major Chambers, of the latter regiment; a party of packers under Chief Packer Moore, and 250 Crow and Shoshone or Snake Indians under Chief Washakie, of the latter tribe -- in all, about 1,500 men broke permanent camp on Goose Creek and marched north in the direction of the Yellowstone River. The infantry, with the exception of the camp guard that remained with the wagon train under command of Major Furey, quartermaster, were mounted upon pack mules, an improvisation by General Crook not wholly to the taste of Major Chambers. We were provided with four days' cooked rations and saddle blankets had to serve as bedding, since there was no transportation. Of course, there were no tents. Consequently, we were without impedimenta and free to go and come as we pleased. After following the Tongue River Valley for some miles, we marched a little west of north and struck the source of the Rosebud River. The ground had been extremely rugged, and in character was not unlike those sections, in the vicinity of the Black Hills, denominated Mauvaises Terres. When we approached the Rosebud, however, we encountered a beautiful region. It is called, indeed, the Indian Paradise. The appellation "Rosebud" may have been given on this account, or derisively, perhaps, because there are no rosebuds there. "Red as a rose was she" the next day, however, as we shall presently find. While on the march, a few buffalo were seen and killed; and as they appeared to be driven, our friendly Indians concluded that were being hunted by the Sioux. Hence, they immediately halted and began their war dance and song, while several braves were dispatched to scout and ascertain the whereabouts of the enemy. When they returned, they reported signs of a tipi or lodge, so fresh as to indicate that our approach had been discovered by its occupants and that they had fled precipitately. Buffalo meat was upon the fire, burnt to a crisp. Upon receipt of this news a song and dance were again in order, and the mettle of war ponies was tested before we could persuade our allies to resume the march. As nothing further occurred, however, we bivouacked near the Rosebud, in the form of a hollow square, with the animals picketed inside. The night was very cold. Early on the morning of the 17th, the march was resumed down the Rosebud, with General Crook and the mounted infantry and Second Cavalry upon the left bank and Colonel Royall with the Third Cavalry, Captain Mills' battalion in front, upon the right bank, of the river. The command was probably divided in order to shorten the column, and the stream was supposed to be readily fordable. About 8 o'clock our Crow scouts in advance returned rapidly to General Crook and reported the proximity of the Sioux. Immediately all the Indians began to strip themselves and their ponies and, amid great excitement, to dance and sing. Meanwhile, the command was halted and dismounted, and as nothing further happened for some time, even saddle girths were loosened, while the horses nibbled at the grass. In this state, not wholly one of expectancy (because we were getting accustomed to such demonstrations upon the part of our Indian allies), we were suddenly surprised by the sound of shots from in front and the whistling of bullets falling in our midst. With yells of defiance the Crows and Snakes dashed wildly up the adjacent slopes, but retired as quickly, being hard pressed by the Sioux, who fairly swarmed over the ridge. The Third Cavalry was promptly ordered to the left bank of the Rosebud, and Captain Mills, being in advance, succeeded in getting across with his battalion and thereafter was under the immediate orders of General Crook, who directed him and Captain Noyes to deploy and support our retreating Indians, which maneuver they executed in gallant style. Meanwhile, Colonel Royall, with Captain Henry's battalion, succeeded with difficulty in effecting a crossing in his vicinity; and your correspondent saw young Sioux braves ride into our temporarily disorganized ranks and strike at the soldiers with their quirts or riding whips, before they were shot down. The position of Captain Henry's battalion, the last to cross the Rosebud, threw him upon the extreme left of the line, where he deployed and charged; consequently, the writer, who accompanied Colonel Royall personally, witnessed only this part of the fight. The battalion engaged here comprised Captains Henry's, Meinhold's, Van Vliet's, Crawford's, Vroom's and Andrews' companies, the last-mentioned having become separated from Captain Mills' battalion, to which it rightfully belonged. The infantry under Major Chambers was held in reserve by General Crook, near the center. Our entire line was now under fire from the Sioux, who occupied the highest ridge in our front, but shot rather wildly. As we advanced, they retired successively to ridges in their rear and, throwing themselves prone upon the ground, reopened fire while their well-trained ponies grazed or stood fast at the extremity of their lariats, upon the reverse of the slope. The country presented, in fact, a succession of small hills, covered with grass and occasional boulders, but rarely with trees. At first the fighting was most severe upon the right and in the center, but the Sioux, in giving way, retired by our left, where they occupied a high and wooded crest, from which point of vantage Captain Henry's battalion was soon exposed to a heavy enfilading fire that was only checked by a brilliant charge made by Lieutenant Foster, [2nd Lt. James E.H. Foster] Third Cavalry, at the head of his platoon. He was, however, forced to retire by overwhelming numbers, a line of skirmishers being rapidly deployed to cover his retreat. Meanwhile, General Crook had conceived the idea that an Indian village existed at no great distance in the valley of the Rosebud, and Captain Mills and Noyes were dispatched to find and attack it, while the infantry and friendly Indians were held in check in the center, to which point Captain Henry's battalion was ordered to withdraw. Evidently the intention was to march the entire command upon the supposed site of the village. Nothing had been accomplished by our repeated charges except to drive the Sioux from one crest, to immediately reappear upon the next. Casualties occurred among them, of course, as with us, but beyond their indefinite equalization, nothing tangible seemed to be gained by prolonging the contest. When we took a crest, no especial advantage accrued by occupying it, and the Sioux ponies always outdistanced our grain-fed American horses in the race for the next one. In obedience to instructions, Colonel Royall now ordered Captain Henry's battalion to withdraw, and it was during this movement that the most of our casualties occurred. The men were dismounted and deployed in line of skirmishers, which constantly covered the led-horses as they slowly retired from one ridge to another. Captain Henry, himself, was in immediate command. But the instant this retrograde movement began, the Sioux appeared to construe it as a retreat and doubtless believed they had inflicted a severe loss upon us. From every ridge, rock and sagebrush, they poured a galling fire upon the retiring battalion, encumbered with its led-horses. They seemed, indeed, to spring up instantaneously as if by magic, in front, in rear and upon both flanks. Our casualties, compartively slight until now, were quickly quadrupled. The ground to be traversed was such that it was difficult to retire and protect the movement. Seeing this, Colonel Royall sent Adjutant Lemly to ask General Crook to station two companies of infantry with their longer range rifles upon the crest in front, from which to cover his withdrawal up the exposed slope; and Captains Burt and Burroughs, of the Ninth Infantry, with their respective companies, were promptly posted for this purpose. At the foot of the hill there was a wide ravine, deep and difficult of passage; and here in the confusion of mounting, quickly as commands were given and obeyed, five men fell dead and as many more were wounded. Some of the led-horses unfortunately escaped and galloped madly away, leaving their troopers at the mercy of the savage Sioux, who now swarmed in the ravine. Many of them appeared to be without firearms, for they used bows and arrows or spears. One of our wounded, who was subsequently recovered, relates a sad story. Separated from their horses and saddle pouches, in which they carried extra ammunition and that in their cartridge boxes having become exhausted, several of our men, led by Sergeant Marshall, of Troop "F," Third Cavalry, clubbed their carbines and fought bravely to the last. One poor lad, a recruit, with an insane idea of surrender or because he preferred a fatal bullet from his own piece to the torture of being transfixed by spear and arrows, calmly gave up his carbine, handing it to the nearest Sioux, and was brained instead by a blow from its butt. Captain Guy V. Henry, who had fearlessly exposed his life during the preceding fight and had been brevetted brigadier general for gallantry during our civil war, now fell from a terrible wound through his jaw and the roof of his mouth. He was assisted to mount his horse by two Crow Indians who had been conspicuous for their bravery; and with remonstrances against leaving his men, he was hurried to the field hospital. The last to come up the slope was Colonel Royall, an old soldier of the Mexican War, who had seen hard and constant service in our army, principally upon the plains and frontier. He ascended the hill calmly and without precipitation, the bullets whistling near him and raising a cloud of dust about him and his horse. Naturally he was chagrined at such an unfortunate issue to his withdrawal, but he had obeyed his instructions under very difficult circumstances, and those instructions were doubtless the only ones that should have been given at the time. The Sioux had evidently made every exertion to cut off and, if possible, annihilate Captain Henry's battalion and, after witnessing its escape from such fate, they silently disappeared. Captains Mills and Noyes, meanwhile, had likewise received orders to return to the main body, as General Crook feared that they, too, might be attacked and overwhelmed by superior numbers. The Sioux had not been believed until then to be in such large force; but the command having once more assembled, the march upon the supposed site of the village was resumed, General Crook and our allied Indians marching in advance, while the troops of Captains Van Vliet and Crawford served as flankers, the only time during the entire campaign when such disposition was made. The trail of the retiring Sioux now entered the canyon of the Rosebud not unlike a muskrat slide in a pond. It was narrow and precipitous. Beyond, there appeared to be a veritable gorge with timbered cliffs and lateral ravines, in which the entire Sioux tribe might have been concealed. When our Crow and Snake Indians reached this point, they refused to proceed farther, and when urged by General Crook, some of them replied in the few English words of their vocabulary, which were more emphatic than polite. They were, in fact, unquotable. Our Kanaka scout and interpreter, Frank Gruard [Frank Grouard], who had lived many years among the Indians, now explained their reluctance to proceed, while the entire column halted. The Crows, it seems, had once been enticed into this very defile, which is several miles in length, and they had been massacred almost to a man by the wily Sioux, who literally lined its almost perpendicular sides. They called it the "Valley of Death." Finding further exhortations useless, General Crook now recalled his Hankers and returned to the scene of our morning's combat, where the infantry was still guarding the field hospital. Here we bivouacked for the night, without incident. [Note: here's Grouard's account of this incident.] An enumeration of our casualties is now in order and a painful but necessary task it is. ROLL OF HONOR Killed Third Cavalry-Sergeants: Marshall, Newkirken; Privates: Roe, Allen, Flynn, Bennett, Potts, Connors, Mitchell. Snake Indians-One. Total killed, 10. Wounded Third Cavalry-Captain Henry; Sergeants O'Donnell, Mayher, Groesh, Crook; Corporal Carty; Trumpeters Edwards, Snow; Privates: Steiner, Herold, Broderson, Featherly, Smith, Stewart, O'Brien, Lorskyborsky, Kramer. Fourth Infantry-Corporals Dennis, Ferry, Flynn. Crow Indians-Four. Snake Indians-Two. Total wounded, 26. Grand total, killed and wounded, 36. None of our dead or wounded were mutilated, and the former were buried upon the field of combat, fires being kindled over the places of interment in order to conceal them. The casualties among the Sioux were certainly much greater than our own. Many times they were observed lassoing their dead and wounded and withdrawing them from the ridge upon the reverse slope, within reach of their waiting ponies. Their conduct upon the field was admirable, and their riding superb, especially when they first approached and charged, entirely naked with the exception of a breech clout, hideously painted and yelling frightfully. No finer irregular cavalry ever existed. At dusk, General Crook held a council with the Crow and Snake Indians, to whom he proposed a night march with a daylight attack upon the Sioux village, but they resolutely refused to accompany him. They had taken thirteen scalps during the day, and they were satisfied. A Shoshone was seen to drag a Sioux from his pony, disarm him and scalp him alive, afterwards killing him. One of our difficulties in the fight had been the impossibility of distinguishing the foe from our friendly Indians. General Crook had, indeed, ordered the latter to wear red about their heads, but this, as is well known, is a favorite color among all our Western tribes. Its unfortunate adoption only added to the confusion. During the night the writer visited Captain Henry at the field hospital and found him suffering from an intolerable thirst, although no word of complaint escaped his lips. There were no invalid stores at hand, but finally Lieutenant Rawolle, of the Second Cavalry, produced some red currant jelly (probably the only delicacy among the fifteen hundred men present), which, although almost insoluble, was partially disintegrated in water and furnished a grateful relief to the wounded officer. Otherwise, the night passed without incident, although we had expected that the Sioux would attempt to stampede our animals. Not a shot was fired. The next morning General Crook, handicapped by short rations and ammunition, and the necessity of caring for the wounded, determined to return to our permanent camp and await reinforcements. The Sioux had proved more numerous than he expected. Litters and travois (adopted by the Indians from the French voyageurs) were therefore improvised for the wounded and we were soon en route. The former were suspended between two mules, while one end of the poles of the latter traveled upon the ground. The locomotion was uncomfortable in the extreme and, despite all precautions, Captain Henry was once or twice thrown out bodily. On the night of the 18th inst., we bivouacked in sight of the Little Big Horn River, the proximity of which was too much for our valorous Crows, and shortly after dark they left us for their agency. Yesterday we reached our former camp, where we found everything in statu quo; and today, it was transferred to this spot, near which the Tongue River issues from the Big Horn mountains. Here we are to await the return of the wagon train with rations from Fort Fetterman, whither it is now marching, accompanied by the wounded in ambulances and guarded by three companies of infantry. The Snake Indians will remain with us, but will depart in a few days for their villages, near Camp Brown. The "Fight on the Rosebud" is still the all-absorbing topic of conversation, and some of its incidents are rather severely commented upon. It is not my business or purpose to criticise. General Crook has shown great energy in the inception and progress of the campaign. He hoped to surprise and certainly destroy the Sioux village, and is doubtless deeply disappointed at the frustration of his plans. His enemies say that he was outgeneraled. [Note: Oglala Sioux war chief Crazy Horse was the principal commander of the joint Sioux - Cheyenne force at the Battle of the Rosebud]. That his success was incomplete, must be admitted, but his timely caution may have prevented a great catastrophe. He has chiefly become famous as an Indian fighter among the Apaches in Arizona, but the mounted and nomadic Sioux are a more difficult proposition. No doubt he will eventually solve the problem. He has much of the Indian in his composition, for he is as taciturn and abstemious and is, moreover, a thorough backwoodsman, an admirable scout and a wonderful hunter. One who knows him well says he could live on acorns and slippery elm bark! The number of Sioux taking part in the engagement is variously estimated at from two to five thousand, but the writer believes the former figure is more nearly correct. Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull are thought to have been in command. Both have proved wily diplomatists in council, and in this fight they showed themselves tacticians, if not strategists, quick to observe and prompt to take advantage of everything that favored or strengthened their position. [Note: Lemly didn't realize it at the time, but actually Crazy Horse's victory over Crook at the Rosebud was a strategic masterstroke that set up the Indians' triumph on the Little Bighorn eight days later.] Their scouts had doubtless been eagerly watching our advance, while the main body was quietly awaiting our arrival with the intention of entrapping us, as the Crows contended, in the gruesome yet beautiful "Valley of Death." The position selected was admirable. The canyon of the Rosebud is said to be fourteen miles in length, and a similar gorge exists in the Tongue River. Now, the general theory of both our attacks is this: the Sioux were determined to give us battle, provided we permitted them to choose their own ground, and they had selected either of these defiles. Both are surrounded by country remarkable for its defensive qualities. While we were on Tongue River, becoming impatient and misapprehending our delay, they attacked us with the design of leading us into the defile on that stream. In this they were disappointed; but the Rosebud, our other available avenue to the Yellowstone, furnished them an equally good opportunity. Our scouting Crows, however, discovered their presence and misconstruing our halt, probably alarmed at our force and the number of our Indians, or fearful of a night attack, they concluded to force the issue immediately. General Crook appears to think our advance was unexpected and that the fight was but a demonstration to enable them to remove, if not the village itself, their families and principal effects, which is not improbable. I repeat, his prudence may have saved us from a great disaster. It is also thought that the disappearance of the Sioux from the field may have been due to lack of ammunition. Our own friendly Indians almost exhausted the forty cartridges per man issued to them, that is, they fired nearly 10,000 rounds, which is not saying much for their marksmanship. One fact was clearly demonstrated during the engagement - the superiority of the Indians as skirmishers. An unfortunate feature of the fight, already alluded to, was the impossibility of distinguishing between the Sioux and our friendly Indians. We fired many shots at the latter, no doubt, while the former as frequently escaped us. This was one of the causes of the dissatisfaction of the Crows and Snakes. The officers of General Crook's staff, Captain Nickerson and Lieutenants Bourke and Schuyler, as well as the adjutants of the subordinate commands, were much exposed while carrying orders, and several had their horses wounded. Lieutenant Bourke gallantly rescued Trumpeter Snow, who was shot through both wrists, by catching his runaway mount and bringing both helpless rider and animal back to our lines. In England, this act would have been rewarded with the Victoria Cross! [Note: here is Lt. John Bourke's account of saving Snow.] It is understood that General Crook has sent for the Fifth Cavalry, five more companies of infantry and a battery of mountain guns - a weapon never before used in our Indian warfare, and that may go far to solve the problem. Meanwhile, we can not complain of our surroundings. Cloud Peak towers nearly 13,000 feet above us. Fed by its melting snows, the Tongue or Talking River (Degi-agie, of the Indians) has cut a deep gorge, through which its waters, clear as crystal, pure and cold, find their way to the plain in a thousand leaping cascades and foaming pools. Myriads of brook trout disport in its rocky depths or poised and alert, watch eagerly the rippling surface for floating fly or bait. The almost perpendicular canyon walls admit deep and timbered ravines, which give shelter to deer, elk, bear, and occasionally buffalo. The mountain sheep make their home beyond, among jutting peaks and projecting crags, where human footsteps have never trod. Here grows a hardy laurel, at a less altitude flourishes the birch and pine, while still lower are cottonwood groves. Upon the banks of the stream are found numerous varieties of ferns and beautiful and verdant moss. In close proximity to our camp, there are many ponds, formed by beaver dams and filled with fine salmon or rainbow trout. Already the soldiers are making nets of commissary twine. Just fancy seining for trout! The Papers of the Order of Indian Wars, compiled and edited by John M. Carroll, The Old Army Press, 1975, p 13 - 18

|

||||||||||