|

|||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... William Slaper's Story of the Battle

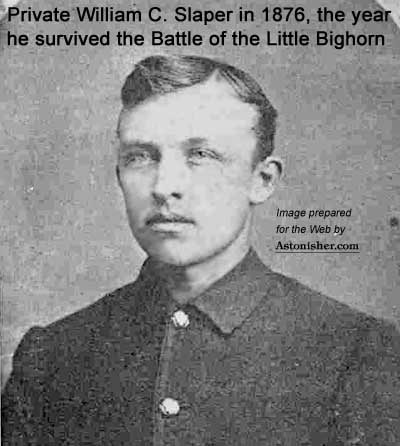

PRIVATE WILLIAM SLAPER'S ACCOUNT A TROOPER WITH CUSTER THE THRILLING EXPERIENCE OF TROOPER WILLIAM C. SLAPER, M COMPANY, SEVENTH CAVALRY, IN THE BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIG HORN.

I stopped and read it. Then I wondered if they would take me as a soldier. Half-heartedly I went upstairs to the office, almost hoping I would be rejected. I told the recruiting officer what I was after. He asked me many questions, and finally I was requested to disrobe for a physical examination. This examination was a very rigid one, because out of ten applicants that morning, but two were accepted, I being one of them. There and then I took an oath to serve Uncle Sam to the best of my ability, for the regal sum of $13 a month "and found". The $13 were always forthcoming, but the "found" part I often found wanting. At that time, any young man wearing the uniform of a United States soldier was looked upon as an idler -- too lazy to work. Being in my own home town, and well known, I felt somewhat ashamed of being seen in my uniform. [Note: by comparison, Mitch Bouyer, half-breed interpreter/scout, was being paid five times as much, or $10 a day.] I had a sweetheart, of course, and naturally wanted to see her, although I remained indoors most of the time. However, as the time of my departure drew near, I ventured forth one afternoon to pay her a visit. I thought by making use of back alleys and unfrequented streets, I might reach her home undetected; but someone who knew me reported it at my home, and this brought my older brother down the following morning to investigate the matter, and, as he said, "to get me out of the army." As I was under age, it was lucky for me that I managed to get my brother's ear before he reached the recruiting office. I took him to the room I had been occupying, and told him if he "gave me away" they could send me to prison for two years for making a false statement regarding my age. He finally concluded to let me go ahead, but first commanded me to go home and see my mother, as she knew where I was and wanted to see me. I found she had met with an accident whereby she had broken her arm in two places. When she saw me in army uniform, she fainted. That was too much for me! Kissing her, I rushed from the house, leaving my mother in the care of my sister. Mother had a dread of war - and with good rea son. My father, my mother's brother, her brotherin-law and a cousin all lost their lives during the first year of the Civil War. It had made life hard for her, as there were five of us children. Doubtless she feared that I never would come back home to her again -- but I did, after five years' service. Mother lived only three months after my return, however. A few days later, twenty of us recruits were sent to Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis. Here we remained about six weeks, where we were instructed in the dismounted drill, and given some preliminary training at stables. We were taught how to groom a horse in regulation style, by a crusty old sergeant named "Bully" Welch, a character whom all old cavalrymen of that day will remember.

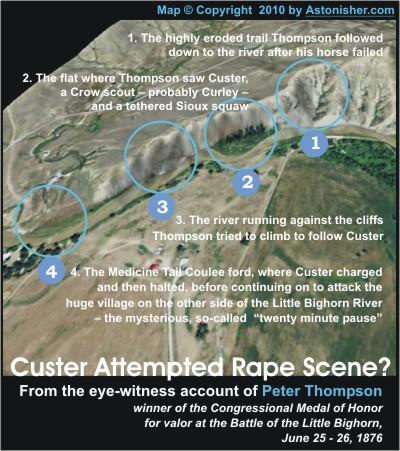

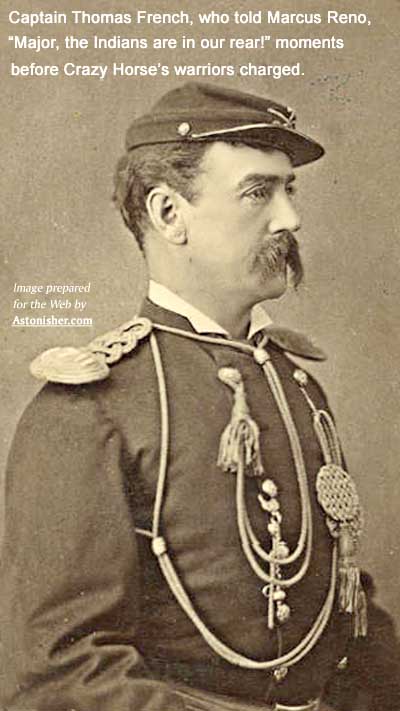

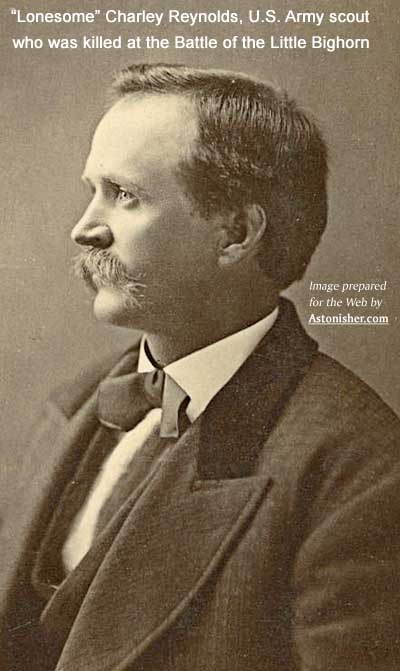

Both Lieut. Sturgis and I were assigned to M Company. We left St. Louis in good marching order, our destination being Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, Dakota, on the Missouri River, then headquarters for the Seventh Cavalry. A little incident that took place en route will perhaps amuse the reader. While stopping for coffee and something to eat at Fargo, Dakota, we had about two hours to wait. An Irish sergeant in charge of our car-seemingly an old veteran instructed a bunch of recruits to go to a certain saloon not far from the station, take their canteens and guns, and pawn or trade the weapons for liquor, and to bring the liquor back in their canteens. On their return with the whisky, he then took a squad of recruits, armed them as guards and marched them over to the saloon. Here he threatened the proprietor for buying government arms, and immediately confiscated the pawned weapons! He thus secured plenty of whisky at no expense. I thought myself that it was a pretty clever trick. Needless to say that from Fargo to Bismarck that night, the sergeant's car contained a bunch of noisy and hilarious troopers. However, we reached Bismarck in good shape, where we were ferried over the Missouri River to Fort Lincoln. Here were six companies of the Seventh Cavalry stationed. We fresh recruits were lined up and assigned to our respective companies, I being, as stated previously, assigned to M Troop, which had just got in from a scout. A day or so later we were started for Fort Rice. Here we passed an uneventful winter, and here I got a taste of real cold weather, the thermometer often reaching 40 degrees below zero. I remember that among other duties, we cut ice and filled the big ice house later to be enjoyed by the infantry who were sent to guard the (fort, while we of the cavalry were out campaigning on the hot, dry, dusty plains, drinking alkali water. When spring arrived, we were ordered back to Fort Lincoln, where we went into camp, having received instructions to make ready to join the expedition to be sent out against Sitting Bull and his hostile warriors of the Sioux nation, who were then leaving their reservations in large numbers, and committing all sorts of depredations. There were many sub-tribes of the Sioux who "jumped" their reservations with their families and plenty of extra ponies, all heading to meet at a general rendezvous, later found to be established along the Little Big Horn River, in the territory of Montana. Some months previously, Capt. Tom Custer, brother of the general, had been sent to Standing Rock Agency, on the Missouri River, about 40 miles below Fort Rice. The object of his trip was to arrest an Indian named Rain-in-the-Face, who was wanted for the murder of Dr. Honzinger, an army veterinarian, and a Mr. Ballaran, an army post sutler, who had strayed from their command. After some hazardous maneuvers, Capt. Custer, through the assistance of Charley Reynolds, General Custer's chief of scouts, secured the Indian, and took him to Fort Lincoln, where he was placed in the guardhouse. One night, several prisoners broke out, among them being Rain-in-the-Face, who immediately joined the hostiles and swore eternal vengeance against Capt. Tom Custer. It was on the 17th day of May, 1876, that my regiment left Fort Abraham Lincoln. Gen. Alfred H. Terry was the commanding officer of the entire expedition, but the Seventh Cavalry itself was under the immediate command of General Custer. It was said to be the best equipped regiment as to horses, men and accoutrements, that Uncle Sam had ever turned out. Custer was known to be very strong for getting only the best in horses and men, and for securing all the conveniences which that early day afforded. There was little enough in the way of comfort at that time on the then unsettled plains of the northwest. Being only a "kid" at the time, I paid but little attention to passing events, such as keeping a diary, as some of the older men did, so at this distant day I am unable to give dates, names of camping places, etc., as readily as I would wish. I was only in the "shavetail" class, having had no real experience in roughing it, much less of Indian fighting. But I was destined to get my full share ere another six weeks had passed. The first day's march was a very lengthy one, and we camped on Little Heart River. There was some excitement on this first day's march, as some of the horses were very unruly and hard to manage after their long winter's rest; and having been well fed, they were ready to "go". In camp that night, there was more excitement. The prairie all about us was on fire, and we were kept busy fighting the flames to prevent their spreading through the camp. However, it did but little damage, and we shortly thereafter had a chance to rest. All went well until June 1, when we were in the Bad Lands of the Little Missouri. Retiring as usual. that night, we were surprised the following morning to discover that we had been snowed in. We were using "pup" tents, two men to the tent, which left but little room for anything else. It turned very cold, and was mighty uncomfortable for both men and horses; but we passed through it with no great harm being done. Nothing worth special mention occurred thereafter until we reached Powder River. Attached to the expedition were four companies of the Second Cavalry, some artillery and some infantry. At the Powder River, our wagons were all sent back. Our sabers were also here boxed and returned; no one, not even an officer, retaining this weapon. The regimental band also was sent back. Thereafter pack mules carried the rations, extra ammunition and supplies of whatever nature were taken along. Some scouting was done from here, and taken altogether, it looked very much as if trouble would loom on the horizon ere long. Rumors of all sorts were floating about the camp, but nothing official was reported. On June 22d, we left our Powder River camp. General Terry had tendered Custer the use of four companies of the Second Cavalry, but they were declined, Custer remarking that he could whip any Indian village on the Plains with his own regiment, and that extra troops would simply be a burden. He also declined the tender of the Gatling guns. Nothing of special interest occurred on the 22d. the march being but a short one, probably of twelve or fifteen miles. The next day we marched about thirty miles (as I recollect) and the following day about the same; but at some hour in the night we were called out and made ready to make a night march. This has always been a puzzle to me, since it was given out that we were to meet General Terry in the neighborhood of the Big Horn River, with the balance of his command on the morning of June 27th. I do not claim to know what orders General Custer had from General Terry about this, save from the written instructions given Custer by Terry, which are now public and which doubtless every student of the Custer fight has read. It seemed to be the general understanding among the men that Custer and Terry were understood to have agreed to meet somewhere in the valley of the Little Big Horn on June 27th. This forced night march had much to do with the worn condition of our horses during the battle of the Little Big Horn. [Note: Peter Thompson was one of the Seventh Cavalry troopers whose exhausted horse gave out as Custer and his men were charging to attack the village on the other side of the Little Bighorn.] The grazing had been poor for several days, and as we were traveling in light marching order -- that is, without wagons -- there was little, if any, grain for our horses. As I recall, it was about daylight when we halted and made coffee. I remember this very distinctly, because I did not get any of the coffee, having dropped down under a tree and fallen asleep, holding to the bridle-rein of my horse, and I did not awaken until called to fall into line. We did not unsaddle at this halt, so the animals secured but little rest. This was on the fateful morning of June 25th, when so much was destined to happen. We all knew that we were on a hot Indian trail, and likely to run into the savages at any moment. Excitement began to grow, and every move was watched with curiosity and intense eagerness. Throughout the morning we were traveling quite rapidly. Toward noon there was a halt, and General Custer called his officers together and gave them their instructions. It so happened that my company, M, under Capt. Thomas French, Company A, under Captain Moylan, and Company G, under Captain Wallace, were elected to go under the command of Major Marcus A. Reno. Of course we did not know at that time what General Custer's plans were, or how many companies he took with him, but later learned that Companies C, E, I, F and L were under his immediate command, and Captain Benteen was given Companies H, K and D, while Company B was to guard the pack-train, under the command of Captain McDougal. As I recall it, it was [Captain Frederick] Benteen and his command which started on to the left. General Custer and his command went straight ahead along the little tributary of the Little Big Horn River, but on the right bank of the stream, while Reno and his command marched parallel to Custer on the left bank. Soon after this, Adjutant Cook came direct to Reno from Custer with some instructions. Then we took a rather sharp angle to the left, and things began to liven up. We were then trotting our horses and going down a long hillside which took us to the Little Big Horn River, which we crossed. I believe it was Company M which had the advance and was the first to ford the river, Company A following, with G Company in the rear. Soon commenced the rattle of rifle fire, and bullets began to whistle about us. I remember that I ducked my head and tried to dodge bullets which I could hear whizzing through the air. This was my first experience under fire. I know that for a time I was frightened, and far more so when I got my first glimpse of the Indians riding about in all directions, firing at us and yelling and whooping like incarnate fiends, all seemingly as naked as the day they were born, and painted from head to foot in the most hideous manner imaginable. We were soon across the stream, through a strip of timber and out into the open, where our captain ordered us to dismount and prepare to fight on foot. Number Fours were ordered to hold the horses, while Numbers One, Two and Three started for the firing line. Our horses were scenting danger before we dismounted, and several at this point became unmanageable and started straight for the open among the Indians, carrying their helpless riders with them. One of the boys, a young fellow named Smith, of Boston, we never saw again, either dead or alive. [Note: click here for more info on Americans whose bodies were never found.] In forming the firing line we deployed to the left. By this time the Indians were coming in closer and in increasing numbers, circling about and raising such a dust that a great many of them had a chance to get in our rear under cover of it -- where we found them on our retreat! It was on this line that I saw the first one of my own company comrades fall. This was Sergeant O'Hara. Then I observed another, and yet another. Strange to say, I had recovered from my first fright, and had no further thought of fear, although conscious that I was in great peril and standing a mighty good chance of never getting out of it alive.

When I got to my horse there were not many of us left in the timber that I could see. Soon after, Private Henry Koltzbucher who was "striker" for Capt. French, was shot through the stomach, just as he was in the act of mounting his horse. He fell to the ground, and I saw Private Francis Neely dismount to help him. I thereupon got off my own horse and helped Neely drag the wounded trooper into a clump of heavy underbrush, where we thought he might not be found by the Indians. Wm. E. Morris, another comrade, came up at this juncture and helped us care for Koltzbucher. We saw that he was probably mortally wounded, so we left him a canteen of water and hurriedly mounted again, dashing toward the river in the wake of our flying trooper comrades. After the battle we found the body of Koltzbucher where we had dragged him. He was not mutilated, and consequently had not been discovered by the Indians or their squaws in their fiendish work of killing and mutilating our comrades who had been helplessly wounded in the river bottom.

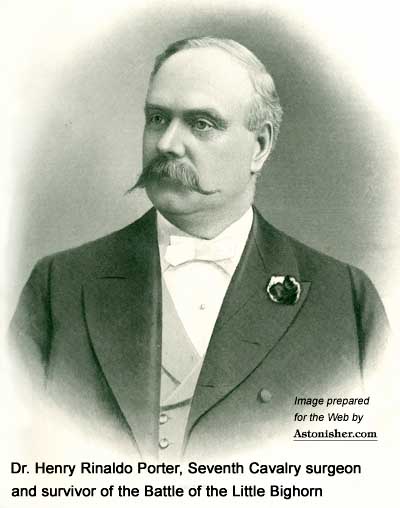

My own position was decidedly precarious. As I urged my horse through the water I could see Indians in swarms about the ford above me, and many lashing their ponies to reach that spot, paying no attention to me. One reason for this was that I was alone, and they were doubtless looking for bigger game. Bullets were cutting the air all about me, however, as there were Indians on both banks, as well as in the water, fighting hand-to-hand with the troopers. Death seemed to ride on every hand, and yet a kind Providence must have been watching over me, for I crossed the stream unscathed. It was at the ford crossing where many of the men met their death, but in the retreat. to the river and the climb up the steep bluffs on the opposite side, some twenty-nine troopers were killed. I believe one reason why so many of the men escaped was because of the intense dust which was raised by the horses and ponies of the combatants. It hung in dense clouds, and it was almost impossible to see fifty feet ahead in any direction. With fully twenty-five hundred or three thousand Indians racing their ponies about through that dust-laden plain, one can understand better the explanation of the situation. After getting across the river, I had the steep bluffs to climb. These were so very abrupt that many of the already-wearied horses were unable to carry their riders to the top, and many of the men had to dismount and lead their exhausted animals, all the time being under a murderous fire from the Indians hidden in the brush along the river. On the way up I passed the body of Dr. De Wolf, one of our surgeons, who had been shot and killed while trying to gain the top. I arrived at the crest of the hill without even a scratch. Here I came upon Captain French with about twenty of the men, and I joined them. Capt. French was as "cool as a cucumber" throughout the entire battle, and although I searched his face care fully for any sign of fear, it was not there. He had such perfect self-control that I had to admire his courage and bravery, and was indeed glad to be under his leadership. I was, however, considerably worried about the rest of the command, and where Custer was and why he had failed to support us as he had promised to do. It looked to me as if we would be wiped out before any assistance arrived, as the Indians were now swarming up the bluffs after us, seeking places of advantage where they could completely surround us. It was not long before Capt. Benteen was seen coming our way. I did not know where he had been or what he had been doing with his three companies, but I do know that they did not show the wear and tear of the Reno "remains". Had Reno not made that move out of the river bottom when he did -- just in the nick of time -- we could all have fared the fate of Custer and his men, without any assistance from any one. Even yet, I cannot understand why Benteen was not at hand where he could have assisted Reno in the fight in the river bottom. Of course he had his orders, but what they were I do not know. But after he joined us on the hill, we shortly thereafter all mounted and started in the direction that Custer was supposed to have gone. But we did not get very far. The Sioux had such a countless horde of warriors there, and they met our advance with such a staggering fire, that we were compelled to turn about and retreat to our first position on the hill. Even here, we were not in a protected position. There were higher ridges than the one we were on, which were immediately occupied by Indian sharpshooters, who poured heavy volleys down upon us. However, we were in the best position we were able to get in the limited time at hand. Here we laid out a hospital, with the horses staked around the outside. We then formed in line of battle outside the horses, and the fighting commenced with renewed vigor on both sides. We were ordered to lie flat on our stomachs and stay down, and not to expose ourselves, for the least sight of any portion of the body was the signal for a volley from the Indians. It was not long before we were carrying more wounded men to this improvised hospital. There were many redskins on the higher hills which our short-barreled carbines could not reach. Finally our first sergeant joined the line at this point. He carried a special make of rifle - his own private weapon, and with it was enabled to throw bullets into the midst of the Indians there, and he soon silenced their fire. While in this line, Capt. French was about in the center, giving orders as coolly as though it was a Sunday school picnic. He would sit up tailor-style, while bullets were coming from the front and both sides. I could but marvel that he was not hit. Without appearing to be in the least excited, he would extract shells from guns in which cartridges would stick, and pass them loaded, then fix another, all the time watching in every direction. We were not very well entrenched, as I recall that I used my butcher knife to cut the earth loose and throw a mound of it in front of me upon which to rest my carbine. At one time a bullet struck the corner olf this mound, throwing so much dirt into my eyes that I could scarcely see for an hour or more. That same afternoon while lying face down on the ground, a bullet tore off the heel of my left boot as effectually as though it had been sawed off! [Note: this shot could have been fired by Oglala Sioux marksman White Cow Bull.] That was as close as the Indians ever got to me, but I saw many of my comrades who fared worse. With all the sad happenings in that hell-hole, there were yet some amusing incidents. In my company was a young fellow known as "Happy Jack", because of his jovial disposition. During all that leaden hail that fell about us, I could hear "Happy's" hearty laugh ring out at a distance, although I could not imagine the cause of it, as I didn't see anything to laugh at; but it cheered me and made me feel a bit braver. Another time I was helping drag a wounded comrade into the hospital. We were compelled to drag him because we dared not expose ourselves. On the way back we started to walk out from, the hospital site, instead of creeping out. My comrade had just reached the horse line when a bullet struck him behind the ear. Fortunately it was merely a glancing shot, passing through his ear. He tumbled to the ground and rolled over and over until I had a chance to examine him and assure him he was not seriously hurt. I had only just returned to my position on the firing line when the man next to me was shot through the shoulder and disabled. The firing was very heavy all through the afternoon of the 25th, and continued until dusk, which was about 9 o'clock in that region at that time of year. After that, we had a little respite, and took occasion to strengthen our defenses and make better breastworks. At peep of day on the 26th, the fighting again commenced with renewed vigor. Just about daylight a stray pack-animal with the pack yet on its back, wandered past our line, and in order to relieve the poor beast of its burden, two troopers and myself arose to our feet. Having done some packing, I was quite handy in untying the ropes, but we had only just started when some Indians caught sight of us and gave us a volley. A stray shot cut off the corner of a hardtack box in the pack. We managed to get the pack loose, but did nothing more, getting back to our places on the line as quickly as possible. These were the first shots fired on the morning of the 26th, which was another busy day all around for both troopers and Indians. We had been kept awake the night before by Major Reno and other officers who walked about among us to see that none were asleep. It was a hard task to refrain from dropping off, after the excitement of the previous day, but we had little chance to relax.

I have read in Capt. Godfrey's account of these water volunteers that all the men were rewarded with medals of honor by Congress. I never received any such medal, nor do I think any other man did. If so, I never heard of it. In our venture to the stream, we found Trooper Mike Madden lying in the coulee, shot through the ankle. Mike was a big husky fellow and had accompanied the first detachment. He lost his leg in the hospital, where it was amputated. An amusing incident happened in connection with it. Before amputating the member, the surgeon gave Mike a stiff horn of brandy to brace him up. Mike went through the ordeal without a whimper, and was then given another drink. Smacking his lips in appreciation, he whispered to the surgeon "Docther, cut off me other leg!" Later on, Mike was employed in the harness depot of the department at St. Paul. I had made the trip for water with a young comrade named Jim Weeks. On our way back, Jim was hailed by Capt. Moylan, requesting a drink. I was surprised to hear Jim blurt out, "You go to hell and get your own water; this is for the wounded." Nothing more was said, but I know that must have been a hard pill for Moylan to swallow. After carrying the water to the hospital we returned to our places on the firing line. I had just laid down when the man on my left (Henry Rutten) was shot through the shoulder. And thus it went for the balance of the day, with Capt. French still sitting up tailor-style, superintending the firing and defying the Indian bullets without flinching once. I was no longer frightened, in spite of the fact that there seemed no chance of our getting out alive, surrounded as we were by thousands of Indians far better armed than ourselves, and outnumbered a hundred to one.

I observed Reno several times during the fighting on the bluffs, and can well remember his walking about among the men through the night. He would tap a man with his boot and remark, "Don't go to sleep, boys." I cannot understand why he was not shot down while walking about, as none of the troopers were able to make a move without drawing the fire of the Indians. I know it encouraged his fellow-officers as well as the troopers. I have read articles pertaining to this part of the battle of the Little Big Horn in which it was stated that Reno was drunk. This I brand as a lie. At no time did I observe the least indication of drunkenness on the man, nor see him use any liquor. At dusk that evening of the 26th, the Indians had withdrawn to such an extent that we were enabled to lead our poor famished horses down to the water. I could not locate my own, so grabbed another -- a fine black animal, which I later learned belonged to Capt. Weir. After this, I heard no more firing, but we kept our places in line throughout the night. The next morning we had roll call of the company, and many were missing. Through the kindness of John Ryan, who was first sergeant of my company, I have a copy of that roll call as the dead and missing were marked off. Later, we observed an immense dust-cloud coming our way up the valley. Some remarked that it was the Indians coming back, but we soon received word that it was Gen. Terry's command. It must have been an awful shock to him, as he was to meet Custer that very 27th of June so they could attack the Indian village together. When he arrived at our position, he told us, with tears in his eyes, what he had seen of the Custer command. It did not seem possible. This was the first intimation we had as to Custer's fate. It was an awful blow to us, as every man lost friends who were in the companies commanded by Custer. Nobody even dreamed that he could possibly meet with such an overwhelming defeat. Everything was then made ready to move the wounded. Many horses which were badly wounded and unable to go further had to be shot. We were then ordered over to the spot where Custer and his men fell. Here, with a few spades, we were set to work to bury them. We had but a few implements of any sort. All that we could possibly do was to remove a little dirt in a low place, roll in a body and cover it with dirt. Some, I can well remember, were not altogether covered, but the stench was so strong from the disfigured, decaying bodies, which had been exposed to an extremely hot sun for two days, that it was impossible to make as decent a job of interring them as we could otherwise have done. There were also great numbers of dead horses lying about, which added to the horror of the situation. I did not have time to go over the field and make notes, but from what I did see, I gathered that these men were surprised here and killed in a very short space of time. It struck me that many of them had evidently shot their own horses and used them as breastworks until killed. In one instance we found two men lying between the legs of their dead horses. From what I saw of the field, it appeared to me that there was very little time for Custer and his men to make any,sort of a defense whatever. All the bodies seemed naked, which would indicate that as soon as the warriors had finished their bloody work, the squaws had ample time to rob the bodies of clothing and valuables and strip the horses of their saddles and trappings and pack it away unmolested. Doubtless while doing this, the mutilation of the bodies occurred. Some of these disfigurations were too :horrible to mention. After being scalped, the skulls were crushed in with stone hammers, and the bodies cut and slashed in all the fleshy portions. Much of this was doubtless done to wounded men. Many arrows also had been shot into some of the bodies -- the eyes, neck, stomach and other members. I observed especially the body of Capt. Tom Custer, which was the worst mutilated of all. Many arrows bristled in it. It is said that he was killed by Rain-in-the-Face in revenge for being arrested the previous year at Standing Rock agency. His body was lying about twenty feet from that of the general, and close beside that of Adjutant Cook, one side of whose face had been scalped, taking with it his magnificent sideburn whiskers. His body also was badly mutilated. The body of Gen. Custer had not been touched by the Indians. He had been shot twice. Some say the Indians do not mutilate the chief officer, out of respect for his bravery. Others said it was because the Indians wanted to make sure that his white friends would recognize him and know that he had been killed.

I was working a spade on this end of the line of dead and so had a hand in burying this group. I am sure that we used more earth in covering Custer's body, and made a larger mound for it than for any of the others. I have heard it said that there was no certainty that the body of the general was really identified when a party went to the field the following year to remove the bodies of Custer and the officers. I do not think this can be possible, as he was not in the least mutilated. The large mound we erected over his body should have been sufficient to identify his burial spot. It must have been a great satisfaction to the Indians to know that he was killed, as they had a dread and a fear of Custer, as he was known as the hardest-fighting white chief against them. He was a fearless and brave soldier, and many will agree with me that he was also a hard leader to follow. He always had several good horses whereby he could change mounts every three hours if necessary, carrying nothing but man and saddle, while our poor horses carried man, saddle, blankets, carbine, revolver, haversack, canteen, 10 days' rations of oats and 150 rounds of 45-caliber ammunition, which of itself would weigh more than ten pounds -and we had no extra horses to change off. With the forced night march we made to .get to the Little Big Horn, it is no secret why our horses played out before going into action. A number of these worn animals were brought in by the rear guard. A comrade friend of mine - a member of one of the companies with Custer, was fortunate in being detailed to go with the rear guard. His horse had played out and he could not go into action. In doing this forced marching, it was generally understood that Custer disobeyed the orders of Gen. Terry, insofar that we were expected -- as I have stated -- to meet Terry's command on the 27th. I have before me now a copy of the written instructions from Terry to Custer. This order reads in part that Custer should conform to the orders unless he saw sufficient reason for departing from them; and again it reads: "But it is hoped that the Indians, if upon the Little Big Horn, may be so nearly enclosed by the two columns (Terry's and Custer's) that their escape will be impossible." So while this order does not flatly designate June 27th as the time for meeting, yet it shows that Gen. Terry expected to be there with his command when the time for the attack was ripe. It was understood that Custer was under arrest on an order from President Grant, and that his object in going into the fight without Terry, was that if he were to win, he would get all the glory himself, and likely the charges against him would be dismissed. This may have spurred him on to take a desperate chance and make a fatal error. When he first viewed the village from the ridge and saw the immense number of tepees, he must have then observed that his puny force was totally inadequate to cope against the thousands of warriors in the valley below, far better armed than his own command. Again, I, like many others, think he made a mistake in dividing his command in this fight. Had he kept them together and struck the village at one end, he might have mastered them, or at least, have put them to flight. A year or so after the battle I was cooking for Capt. French, and we often had a heart-to-heart talk about the Little Big Horn fight. One day I asked him what he would have done had he been in Custer's place. His answer was, "There would have been no fight." Officers, as a rule, are loth to say anything against another officer, no matter what may be in their mind. So that in all statements made by officers who took part in the battle of the Little Big Horn, none has shown a willingness to speak his mind as to whether Custer did right or wrong in dividing his regiment, or going into the fight before Terry arrived.

After the burial of the dead had been completed, the next task was to move the wounded of Reno's command. Because of the meager facilities at hand, transporting them down to the supply steamer "Far West", which had been lying at the mouth of the Little Big Horn awaiting orders, was no easy task; but we did all that was possible to make them comfortable. Many were carried on travois made from tepee poles left in the deserted Indian village, and while this sort of conveyance was not very desirable over such a rough country, it was the only possible manner of transporting them. After the wounded had been started down the river on their long journey of nearly 1000 miles to Bismarck, the remainder of the regiment joined forces with Gen. Crook's command, and with all the force then at hand, we were strong enough to wipe out any detachment of savages we might meet. But we did not meet them -- for reasons known best to Gen. Crook. Buffalo Bill Cody was at the head as chief of scouts with Gen. Crook. He did not remain with us very long, because of a misunderstanding with Gen. Crook, the nature of which would be but hearsay to me. Since the Little Big Horn fight I have met with many impostors who have recounted their "experiences" on that fatal field, but who were not there at all. I have read, I dare say, a hundred accounts of the death of "last survivors of Custer's command". All such stories are absolutely false, as there were no survivors of Custer's command - every man was killed. One of Custer's Crow scouts, "Curley", long posed as the only living man who escaped. For "Curley" I will say that I do not believe he ever got to the Custer forces, but skirmished his way around the outside until a chance presented itself for him to make his escape undetected. I am certain he was not in the fight.

To begin with -- where he states his horse played out. He was then on the trail of those who went on, and he would naturally travel slow, and would be picked up by the rear guard, as all others were who were in the same predicament, and he would not be allowed to stroll away, as his story states. [Note: Slaper doesn't know what Thompson actually said. What Thompson said is that he was "picked up by the rear guard," as Slaper suggests. The first man Thompson saw was Daniel Kanipe, who was with McDougal because he had carried Custer's "last order" to him. Here is Daniel Kanipe's eye-witness account of Thompson finding the Americans, and Thompson's own account of that same happy moment on the afternoon of June 25, 1876.] Why should he leave the trail, where he was safe, with the troops ahead of him, and troops in the rear coming after him, unless he lost his nerve and went to hide out? [Note: there were actually no "troops in the rear coming after" Custer, nor was Thompson safe on the trail. Short-term, Thompson simply manuevered to try to stay alive. Here is An Anonymous Ree's eye-witness description of Thompson trying to elude the pursuing Sioux on foot after his horse "played out," and Thompson's own account of the same desperate incident.] Then he says he met Jim Watson, and together they trailed along with a wornout horse, and fought straggling Indians for hours afterward. He says he wrote this story -- originally published in the Belle Fourche Bee -- for his children to read, and not for publication. I think he knows that Jim Watson has passed away, or he would not have given it out yet. This man Watson was a chum of mine, all through our five years' service. We botch enlisted the same hour at Cincinnati, and took to each other from the start. From there we went to St. Louis for six weeks, and all this time we were together from early morning until late at night, every day. Then we were assigned to the Seventh Cavalry, and Jim went to C Company while I was assigned to Company M, which separated us on several occasions, being stationed at different forts. We met again as we started on the campaign, and saw each other every day. On the day of the Little Big Horn fight his company was picked as one to go with Custer, but, like Thompson, his horse gave out, and so he had to lead him along until taken up by the rear guard. I was with Major Reno, and some time after the fight in the river bottom, and after settling on the hill for a stand with Benteen and his forces, and the rear guard had come and joined us, I met Watson again, and he related to me how his horse had played out. He had to drop out back of his company, then was picked up by the rear guard. He said nothing of having had any hairbreadth escapes with Thompson, and I am sure Jim would have told me of any such adventures, as we were much together from this time until we were discharged, and went home together as far as Chicago, where he left me to go to Grand Rapids, Michigan, and I went back to Cincinnati, Ohio. I can remember that Jim Watson was badly afflicted with asthma, and I did not think he would live long. I gave him my address and asked him to write to me, but I never heard from him again. [Note: it seems that Slaper is blaming Thompson for the fact that Slaper really wasn't as close to his "chum" Watson as he thought.]

Mr. Thompson bears a good reputation in his home town today as a good citizen, and if he would sit down and write a story of facts only of his experiences in the Custer fight, it would be interesting; but his story, as it stands, will never pass as long as there are any of the old boys of the 7th Cavalry left to dispute it. In conclusion I would state that I have written of this battle just as I saw it and as things presented themselves to my view. Other stories may differ, as each man in his own place saw many things as they happened to him, which others did not see. This story may reach the eyes of some of my old comrades who were with me in the battle, and I am writing it truthfully so that no person can dispute my statements. No one man can write a story of the fight in general (as many have done) without someone to dispute parts of it. A Trooper With Custer And Other Historic Incidents of the Battle of the Little Big Horn by E.A. Brininstool, The Hunter-Trader-Trapper Co., Columbus, OH 1925 p 17 - 56

William C. Slaper was green 21-year old private from Columbus, OH, when he rode with Custer into the valley of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876. Under the command of Capt. Thomas French and ordered with the rest of Reno's men to charge the huge Indian village, he survived the Seige of the Greasy Grass without injury. Slaper's description of the scam that the Seventh Cavalry troopers used to obtain free liquor in Fargo, ND, is one of the more humorous moments in the whole Little Bighorn saga. |

|||||||

I WAS born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, November 23, 1855, working there at various employments until I attained my twentieth year. Early in September, 1875, I found myself out of a job, and while walking along the street, wondering what I had better try next in the work line, I observed the sign, "Men Wanted", in front of the United States Army Recruiting station. Although I had passed that sign numberless times before, it never held any attraction for me until that morning.

I WAS born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, November 23, 1855, working there at various employments until I attained my twentieth year. Early in September, 1875, I found myself out of a job, and while walking along the street, wondering what I had better try next in the work line, I observed the sign, "Men Wanted", in front of the United States Army Recruiting station. Although I had passed that sign numberless times before, it never held any attraction for me until that morning.

After we had buried all the dead on the Custer field, the site of the Reno battle in the river bottom was investigated. The dead there were all buried where they fell. All had been most horribly butchered.

After we had buried all the dead on the Custer field, the site of the Reno battle in the river bottom was investigated. The dead there were all buried where they fell. All had been most horribly butchered.