|

|||||||||||

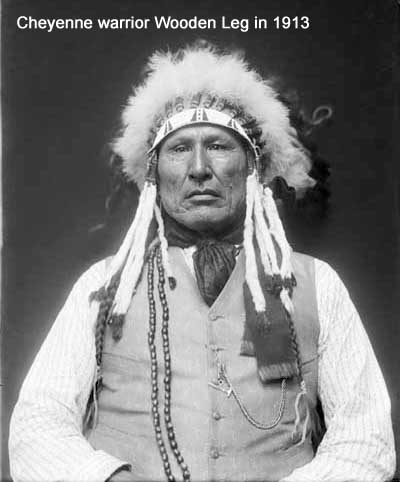

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Wooden Leg's Story of the Battle

CHAPTER XII - SOLDIERS FROM THE SOUTHWARD

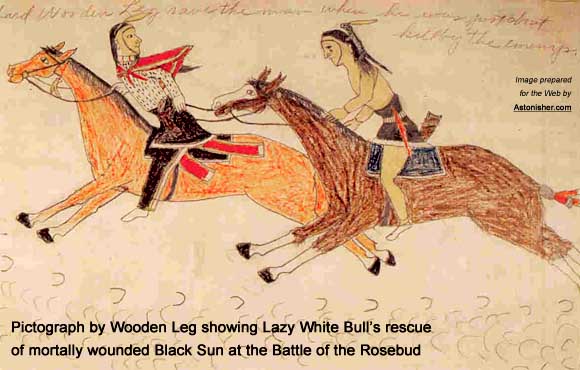

One of our men named Lame Sioux went out to a hill for a look over the country. Pretty soon he began to signal. He had seen a camp of soldiers. All of us got out to look. Yes, this was a soldier camp. We dropped back into hiding. Ourselves and our horses all were put into concealment until dark ness came. Then we dressed ourselves, painted ourselves and went on a night scout for a closer view. We saw the camp fires burning. We worked our way carefully toward them. It was after the middle of the night when we arrived at a point where we could see well the entire scene. But all of the soldiers then were gone. We slept then until morning came. When we went to the abandoned camp-site the first thing to arouse our special interest was a beef carcass having yet on the bones many fragments of meat. The next interesting object was a box of hard crackers. It had been raining, and they were wet, but this made them all the better. We ate what we wanted of them. We cooked pieces of the beef on the fire coals. We enjoyed a fine breakfast. Then we set out on the trail of the soldiers. The trail led us northwestward over the divide and down Crow creek. Near where Crow creek empties into Tongue river we saw the soldier camp.* The time was late in the afternoon. We retreated and skirted around up the river. At dusk we crossed it to the west side. The water was running high. We stripped and tied our clothing in bundles about our necks. We sat upon our riding horses and led our pack horses as they swam through the lively current. We hid ourselves among the trees on that side of the valley and slept until morning. From a cliff the next morning we saw first a band of about twenty Indians riding away from the soldier camp. Were they Crows? Were they Shoshones? We exchanged guesses, but we did not know. We talked among ourselves about making an attack upon them. There was some talk of trying to steal soldier horses. We were anxious to do something warlike, to get horses or to count coups. But the general agreement was that it was too risky. We considered it most important that we return and notify our people on the Rosebud. We did not want to tire out our horses in an effort to get others or to get fighting honors. But we lingered to do some more looking. We saw soldiers walking about their camp. It had been flooded by the high waters. They were splashing about here and there and appeared to be getting ready to travel. We decided it was time for us also to travel. Six of us, including myself, started out toward the hills between us and the uppermost Rosebud. The five other Cheyennes remained behind to see where the soldiers might go. During the day two of these came on and joined us. Before night the final three were with us. "They are coming in this direction," the three reported. We then were on the upper small branches of Rosebud creek. We killed a buffalo there. We hurried in cutting from it some of the choice pieces. We quickly divided up the liver and ate the raw segments. Over a hastily built fire we scantily toasted little chunks of buffalo meat. As we devoured them we spoke but few words. Whatever speech was uttered was in jerky sputterings. Everybody was excited. Every minute or two somebody was jumping up to go somewhere and look for pursuing soldiers. After the food had been bolted we hastened to move on. When darkness had well advanced we stopped for the night. Our horses needed rest and food. We picketed them. We felt safe during the night, so we slept soundly. Before the sun was up we were several miles on down the Rosebud valley. We did not know just where our people were, but we knew they were somewhere on this stream. We found them strung along from the location of our present Indian dance hall there up almost to the present home of Porcupine. We wolf-howled and aroused the people. Cheyennes flocked to learn why we had given the alarm. We went on into camp and reported to an old man. Some Sioux were there, and they carried the news to their people. Soon all of the camp circles were in a fever of excitement. Heralds in all of them were riding about and shouting: "Soldiers have been seen. They are coming in this direction. Indians are with them." Councils were called. Lots of young men wanted to go out and fight the soldiers, but the chiefs would not allow this. Our chiefs appointed Little Hawk, Crooked Nose and two or three others to go scouting and find out about the further movements of the white men. Maybe some Sioux scouts also were sent out. I do not know, but I think they depended upon the Cheyennes to do the work. The Indians all moved camp, going on up the valley about ten miles. Here the Cheyennes chose for their location a spot on the east side of the Rosebud, just across from the present Davis creek and on the land now occupied by Rising Sun. The Sioux following them set their circles on down the creek, the Uncpapas being below the present Busby school. My recollection is we stayed here more than one sleep, but I am not sure. When we left this place we went westward up Davis creek and across the hills beside it, going toward the dividing hills separating us from the Little Bighorn river. It was understood we were on our way to that valley. We camped that afternoon just east of the divide. The place is about a mile north of the present road there, the camps extending northward up a broad coulee full of plum thickets. Dry camp, no water, at this place. One sleep here. The next morning we went on over the divide and down the slopes to what we called Great Medicine Dance creek, but known now to the white people as Reno creek. We stopped where the main forks of the creek come together. Our circles were formed along the valley and on the bench. The Cheyennes were at the advance or west end, the Uncpapas at the rear or east end. From our camp to theirs the distance was about two miles. The grouped camps centered about where the present road crosses abridge at the fork of the creek. Little Hawk and the other scouts returned to us here. They reported the soldiers as being on the upper branches of the Rosebud. The Sioux were told of this report, or they may have had information from scouts of their own. Heralds in all six of the camps rode about and told the people. The news created an unusual stir. Women packed up all articles except such as were needed for immediate use. Some of them took down their tepees and got them ready for hurrying away if necessary. Additional watchers were put among the horse herds. Young men wanted to go out and meet the soldiers, to fight them. The chiefs of all camps met in one big council. After a while they sent heralds to call out: "Young men, leave the soldiers alone unless they attack us." But as darkness came on we slipped away. Many bands of Cheyenne and Sioux young men, with some older ones, rode out up the south fork toward the head of Rosebud creek. Warriors came from every camp circle. We had our weapons, war clothing, paints and medicines. I had my six-shooter. We traveled all night. We found the soldiers * about seven or eight o'clock in the morning, I believe. We had slept only a little, our horses were very tired, so we did not hurry our attack. But always in such cases there are eager or foolish ones who begin too soon. Not long after we arrived there was fighting on the hillsides and on the little valley where was the soldier camp. In this early fighting, one young Cheyenne foolishly charged too far, and some Indians belonging to the soldiers got after him. They shot and crippled his horse. I and some other Cheyennes drove back the pursuers. I took the young man behind me on my horse, and we hurried away to our main body of warriors. Jack Red Cloud, son of the old Ogallala Chief Red Cloud, was wearing a warbonnet. His horse was killed. According to the Indian way, in such case the warrior was supposed to stop and take off the bridle from the killed horse, to show how cool he could conduct himself. But young Red Cloud forgot to do this. He went running as soon as his horse fell. Three Crows on horseback followed him, lashed him with their pony whips and jerked off and kept his warbonnet. They did not try to kill him. They only teased him, telling him he was a boy and ought not to be wearing a warbonnet. Some of his Sioux friends interfered, and the Crows went away. The Sioux told us that young Red Cloud was crying and asking mercy from the Crows. He was my same age, eighteen years old. White Wolf, a Cheyenne almost thirty years old, had a repeating rifle. In drawing this weapon from its scabbard at his left side it was accidentally dis charged. The bullet broke his left thigh bone. He finally recovered and is yet living (1930). He still limps on account of that accidental wound. Until the sun went far toward the west there were charges back and forth. Our Indians fought and ran away, fought and ran away. The soldiers and their Indian scouts did the same. Sometimes we chased them, sometimes they chased us. One time, as I was getting away from a charge, I caught up with a Cheyenne afoot and driving his tired horse ahead of him. My horse also was very tired, so I dismounted and we two drove our'mounts into a brush thicket. There we rested a while. It appeared that all of the Cheyennes were in hiding just then. Chief Lame White Man, the old Southern Cheyenne, rode out into the open on horseback. He called to us for brave actions. Our young men had high regard for him. The Cheyennes came out from hiding and went flocking to him. I and my com panion joined them. It then became the turn of the soldiers and their Indians to get out of our way. The soldiers finally left the field and went back southward, on the trail where they had come to this place. Some Sioux and Cheyennes followed them a short distance, but not far. The soldiers lost or left behind some of the packs from their mules.* We got crackers and bacon and other food material. I found a good white hat and a good pair of gloves. I picked up a little package of something and stuffed it under my belt. As I went riding away, the package rubbed between the belt and my body. The day was hot, and I was sweating freely. My nostrils perceived a pleasant odor. I traced it to the package. I took it from my belt, sniffed at it, then fumbled at the heavy paper and tore off a corner. "Oh, coffee!" My heart was glad. I had something good to take as a gift for my mother. The only naked Cheyenne in that battle was Black Sun. All of the rest of us had on whatever war clothing he owned. I do not recollect having seen there any Sioux who was not dressed in his best. But Black Sun had a special medicine painting for him self. He spent a long time at getting ready. All of his body was colored yellow. On his head he wore the stuffed skin of a weasel. He wrapped a blanket about his loins. The soldiers and enemy Indians fired many shots at him without harming him. Finally some one of them got behind him and shot him through the body. He fell, not dead, but unable to stand up. Some of his friends rescued him. [Note: Black Sun was rescued by the Sioux warrior, Lazy White Bull.] I caught his horse. When we were ready to go back to our camps we put him upon a travois and had his horse drag this bed for him. He died that night, at his home lodge. He was the only Cheyenne killed that day. Limpy was shot in his left side and had his horse killed. Other Cheyennes had slight wounds. One Burned Thigh Sioux was killed during the battle, and one Minneconjoux died after arrival at the camps. I do not know how many other Sioux were killed, but some Cheyennes said there were twenty or more. I think the Uncpapas lost the most warriors. I remember that one of the dead Sioux was a boy about fourteen years old. Black Sun was buried in a hillside cave. I believe that all of the Sioux dead were left in burial tepees on the camp-site when we left there.

All camps were moved again early the next morning after the Rosebud battle. We followed a short distance down Medicine Dance creek and then turned southward across the benches to the Little Bighorn. In present times, where the Busby road joins the graveled highway there is a bridge over the river. About half a mile south of this bridge, on the west side of the highway and on the east side of the river, stood the camp circle of the Uncpapas. The Cheyennes were a mile or more farther up the river. The other four tribal camps were scattered here and there between the Uncpapas and the Cheyennes. There was not here nor at any other camping location a placing of the camp circles in line with one another. The groupings between Uncpapas and Cheyennes were according to the form of the land or the curves of the stream. The only strict rule of camp circle location was that none should be set up ahead of the Cheyennes nor behind the Uncpapas. Six sleeps we remained at this first camping place on the Little Bighorn. We had beaten the white men soldiers. Our scouts had followed them far enough to learn that they were going farther and farther away from us. We did not know of any other soldiers hunting for us. If there were any, they now would be afraid to come. There were feasts and dances in all of the camps. On the benchlands just east of us our horses found plenty of rich grass. Among the hills west of the river were great herds of buffalo. Every day, big hunting parties went among them. Men and women were at work providing for their families. That was why we killed these animals. Indians never did destroy any animal life as a mere pleasurable adventure. Six Arapaho men came to the Cheyenne camp while we were at this place. [Note: these included Waterman and Left Hand.] They said they were afraid of soldiers, as they had killed a white man on Powder river. Many Sioux and some Cheyennes suspected them as spies, but finally all of us were satisfied they wanted to stay with us as friends. They were invited into lodges of different ones of the Cheyennes. Some more of our own people from the reservation joined us here. It is likely some Sioux also arrived, but I am not sure about that. Our plans had been to go up the Little Bighorn valley. But our game scouts reported great herds of antelope west of the Bighorn river. Because of this, the chiefs decided we should turn and go down the Little Bighorn, to its mouth. From there our hunt. ing parties would cross the Bighorn and get antelope skins and meat that we now wanted. These councils of chiefs of all of the tribal circles were held sometimes at one camp circle and sometimes at another. In each case, heralds announced the meeting and told where it would be held. Each tribe operated its own internal government, the same as if it were entirely separated from the others. The chiefs of the different tribes met together as equals. There was only one who was considered as being above all of the others. This was Sitting Bull. He was recognized as the one old man chief of all the camps combined. Almost all of our Northern Cheyenne tribe were with us on the Little Bighorn. Only a few of our forty big chiefs were absent. Two of our four old men chiefs, Old Bear and Dirty Moccasins, were here. Old Bear had been off the reservation throughout all of the past year, while Dirty Moccasins had come to us on the Rosebud. The absent two old men chiefs were Little Wolf and Rabbit, this last one known sometimes as Dull Knife, or Morning Star. Our tribal medicine tepee was at its place in our camp circle, and Charcoal Bear, its keeper, was with it. I believe all of the thirty chiefs of the three warrior societies were present, except Little Wolf, leading chief of the Elk warriors. I do not know how many Cheyennes in all were in the camp.* In fact, I do not know how many of us there were in our tribe at that time. I never knew of any count having been made during those times. We crossed the Little Bighorn river to its west side and set off down the valley. Cheyennes ahead, Uncpapas behind, in the usual order of march. The journey that day was not a long one. After eight or nine miles of travel the Cheyennes stopped and began to form their camp circle. The tribes following us chose their ground, and their women began to set up the villages taken down that forenoon. The last tribe, the biggest one, the Uncpapas, placed themselves behind the others. The Cheyenne location was about two miles north from the present railroad station at Garryowen, Montana. We were near the mouth of a small creek flow ing from the southwestward into the river. Across the river east of us and a little upstream from us was a broad coulee, or little valley, having now the name Medicine Tail coulee. The Uncpapas, at the southern end of the group and most distant from us, put their circle just northeast of the present Garryowen station. The other four circles were placed here and there between us and the Uncpapas. Our trail during all of our movements throughout that summer could have been followed by a blind person. It was from a quarter to half a mile wide at all places where the form of the land allowed that width. Indians regularly made a broad trail when traveling in bands using travois. People behind often kept in the tracks of people in front, but when the party of travelers was a large one there were many of such tracks side by side... Dr. Thomas B. Marquis's Footnotes:1 Prairie Dog creek? Finerty writes that the soldiers were camped there June 8th.-T. B. M. 2 Wooden Leg, Big Beaver and Limpy, each on a separate occasion, went with me and pointed out the exact locations of the 1876 Indian campings on the Rosebud and the Little Bighorn.-T. B. M. 3 General Crook's soldiers, June 17th, 1876. Historians have copied each other in repetitions that the hostiles here were "Crazy Horse and his Ogallalas," and that they were from the "Crazy Horse village" supposed to have been only a short distance down the Rosebud.-T. B. M. 4 The Crow aspect of this same story was told to me by Along the Hillside, an old Crow man who was a scout with Crook. He was one of the pursuers who jerked the warbonnet from the amateur Sioux.T. B. M. 5 Finerty writes that Crook had 1,000 pack mules, and that the Crows and Shoshones joined him on June 14th, at the Goose Creek camp.-T. B. M. 6 At the Northern Cheyenne fair at Lame Deer in 1927 I estimated the encampment at about 1,100. Wooden Leg and some other old men were asked to compare this camp with the one on the Little Bighorn. After a consultation, it was generally agreed that there must have been 1,600 or more Cheyennes in their camp when the Custer soldiers came.-T. B. M. Wooden Leg: A Warrior Who Fought Custer by Dr. Thomas B. Marquis, The Midwest Co., Minneapolis, MN 1931, p 193 - 207

By almost any measure, A Warrior Who Fought Custer is the single most impressive Native American account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Here is Wooden Leg's account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

|

|||||||||||

OUR PARTY of eleven buffalo hunters went over the same low pass that is traversed by the road now going from the Rosebud to Tongue river and Ashland. We did not find any big herd of buffalo. We had killed only four by the time we arrived at Hanging Woman creek. We decided then to go on over to Powder river. We followed Powder river almost up to the mouth of Lodgepole creek. On the way we came across a dead Indian on a burial scaffold. The body had been stripped of all wrappings and of clothing. We wondered if this had been a Sioux, a Crow or a Shoshone. We wondered also who had robbed the body.

OUR PARTY of eleven buffalo hunters went over the same low pass that is traversed by the road now going from the Rosebud to Tongue river and Ashland. We did not find any big herd of buffalo. We had killed only four by the time we arrived at Hanging Woman creek. We decided then to go on over to Powder river. We followed Powder river almost up to the mouth of Lodgepole creek. On the way we came across a dead Indian on a burial scaffold. The body had been stripped of all wrappings and of clothing. We wondered if this had been a Sioux, a Crow or a Shoshone. We wondered also who had robbed the body.