|

||||||||||||

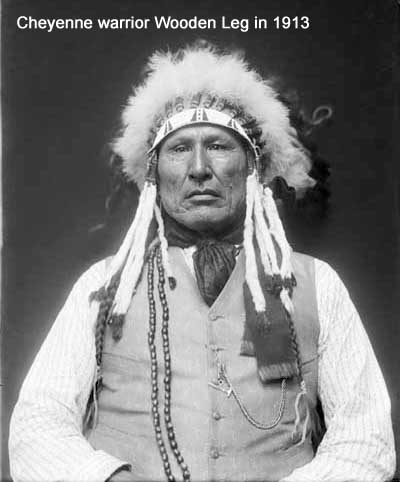

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Wooden Leg's Story of the Battle

CHAPTER IX - THE COMING OF CUSTER

"Soldiers are here! Young men, go out and fight them." We ran to our camp and to our home lodge. Everybody there was excited. Women were hurriedly making up little packs for flight. Some were going off northward or across the river without any packs. Children were hunting for their mothers. Mothers were anxiously trying to find their children. I got my lariat and my six shooter. I hastened on down toward where had been our horse herd. I came across three of our herder boys. One of them was catching grasshoppers. The other two were cooking fish in the blaze of a little fire. I told them what was going on and asked them where were the horses. They jumped on their picketed ponies and dashed for the camp, without answering me. Just then I heard Bald Eagle calling out to hurry with the horses. Two other boys were driving them toward the camp circle. I was utterly winded from the running. I never was much for running. I could walk all day, but I could not run fast nor far. I walked on back to the home lodge. My father [White Buffalo Shaking Off The Dust, or Many Wounds] had caught my favorite horse from the herd brought in by the boys and Bald Eagle. I quickly emptied out my war bag and set myself at getting ready to go into battle. I jerked off my ordinary clothing. I jerked on a pair of new breeches that had been given to me by an Uncpapa Sioux. I had a good cloth shirt, and I put it on. My old moccasins were kicked off and a pair of beaded moccasins substituted for them. My father strapped a blanket upon my horse and arranged the rawhide lariat into a bridle. He stood holding my mount. "Hurry," he urged me. I was hurrying, but I was not yet ready. I got my paints and my little mirror. The blue-black circle soon appeared around my face. The red and yellow colorings were applied on all of the skin inside the circle. I combed my hair. It properly should have been oiled and braided neatly, but my father again was saying, "Hurry," so I just looped a buckskin thong about it and tied it close up against the back of my head, to float loose from there. My bullets, caps and powder horn put me into full readiness. In a moment afterward I was on my horse and was going as fast as it could run toward where all of the rest of the young men were going. My brother already had gone. He got his horse before I got mine, and his dressing was only a long buckskin shirt fringed with Crow Indian hair. The hair had been taken from a Crow at a past battle with them. The air was so full of dust I could not see where to go. But it was not needful that I see that far. I kept my horse headed in the direction of movement by the crowd of Indians on horseback. I was led out around and far beyond the Uncpapa camp circle. Many hundreds of Indians on horseback were dashing to and fro in front of a body of soldiers. The soldiers were on the level valley ground and were shooting with rifles. Not many bullets were being sent back at them, but thousands of arrows were falling among them. I went on with a throng of Sioux until we got beyond and behind the white men. By this time, though, they had mounted their horses and were hiding themselves in the timber. A band of Indians were with the soldiers. It appeared they were Crows or Shoshones. Most of these Indians had fled back up the valley. Some were across east of the river and were riding away over the hills beyond. Our Indians crowded down toward the timber where were the soldiers. More and more of our people kept coming. Almost all of them were Sioux. There were only a few Cheyennes. Arrows were showered into the timber. Bullets whistled out toward the Sioux and Cheyennes. But we stayed far back while we extended our curved line farther and farther around the big grove of trees. Some dead soldiers had been left among the grass and sagebrush where first they had fought us. It seemed to me the remainder of them would not live many hours longer. Sioux were creeping forward to set fire to the timber. Suddenly the hidden soldiers came tearing out on horseback, from the woods. [Note: This was Reno's charge/flight back to the river, which was precipitated by Crazy Horse's flanking charge.] I was around on that side where they came out. I whirled my horse and lashed it into a dash to escape from them. All others of my companions did the same. But soon we discovered they were not following us. They were running away from us. They were going as fast their tired horses could carry them across an open valley space and toward the river. We stopped, looked a moment, and then we whipped our ponies into swift pursuit. A great throng of Sioux also were coming after them. My distant position put me among the leaders in the chase. The soldier horses moved slowly, as if they were very tired. Ours were lively. We gained rapidly on them. I fired four shots with my six shooter. I do not know whether or not any of my bullets did harm. I saw a Sioux put an arrow into the back of a soldier's head. Another arrow went into his shoulder. He tumbled from his horse to the ground. Others fell dead either from arrows or from stabbings or jabbings or from blows by the stone war clubs of the Sioux. Horses limped or staggered or sprawled out dead or dying. Our war cries and war songs were mingled with many jeering calls, such as: "You are only boys. You ought not to be fighting. We whipped you on the Rosebud. You should have brought more Crows or Shoshones with you to do your fighting." Little Bird and I were after one certain soldier. Little Bird was wearing a trailing warbonnet. He was at the right and I was at the left of the fleeing man. We were lashing him and his horse with our pony whips. It seemed not brave to shoot him. Besides, I did not want to waste my bullets. He pointed back his revolver, though, and sent a bullet into Little Bird's thigh. Immediately I whacked the white man fighter on his head with the heavy elk-horn handle of my pony whip. The blow dazed him. I seized the rifle strapped on his back. I wrenched it and dragged the looping strap over his head. As I was getting possession of this weapon he fell to the ground. I did not harm him further. I do not know what became of him. The jam of oncoming Indians swept me on. But I had now a good soldier rifle. Yet, I had not any cartridges for it. Three soldiers on horses got separated from the others and started away up the valley, in the direction from where they had come. Three Cheyennes, Sun Bear, Eagle Tail Feather and Little Sun,1 joined some Sioux in pursuit of the three white men. The Cheyennes told afterward about the outcome of this pursuit. One of the soldiers turned his horse eastward toward the river and escaped in the timber. The other two kept on southward. Of these two, one went off to the right, up a small gulch to the top of the bench. There he was caught and killed. The remaining one rode on toward the mouth of Reno creek. As he neared that point he swerved to the right. He made a circle out upon the valley and returned to the timber just across west from the mouth of Reno creek. Here he dismounted from his exhausted horse and got himself into the brush. The Sioux and Cheyennes surrounded him and killed him. They told that he fought bravely to the last, making use of his six shooter.

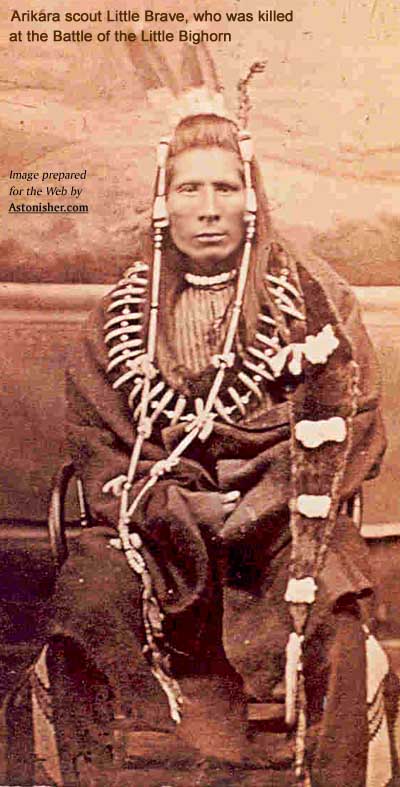

Indians mobbed the soldiers floundering afoot and on horseback in crossing the river. I do not know how many of our enemies might have been killed there. With my captured rifle as a club I knocked two of them from their horses into the flood waters. Most of the pursuing warriors stopped at the river, but many kept on after the men with the blue clothing. I remained in the pursuit and crossed the river. Whirlwind, a Cheyenne, charged after a warbonnet Indian belonging with the whites. The enemy Indian bravely charged also toward Whirlwind. The two men fired rifles at the same moment. Both of them fell dead. This was on the flat land just east of the river where the soldiers crossed. [Note: the other warrior is generally believed to be the Arikara scout Bob-tailed Bull. Arikara scout Red Bear saw Bob-Tailed Bull's horse running terrified with a bloody saddle moments later.]

I returned to the west side of the river. Lots of was, had been killed on the west side of the river. My heart was made sad by this news, but I went on up the hill. I joined with others in going around to the left or north side of the place where were the soldiers. From our hilltop position I fired a few shots from my newly-obtained rifle. I aimed not at any particular ones, but only in the direction of all of them. I think I was too far away to do much harm to them. I had been there only a short time when somebody said to me: "Look! Yonder are other soldiers!" [Note: these were Custer's troops.] I saw them on distant hills down the river and on our same side of it. The news of them spread quickly among us. Indians began to ride in that di rection. Some went along the hills, others went down to cross the river and follow the valley. I took this course. I guided my horse down the steep hillside and forded the river. Back again among the camps I rode on through them to our Cheyenne circle at the lower end of them. As I rode I could see lots of Indians out on the hills across on the east side of the river and fighting the other soldiers there. I do not know whether all of our warriors left the first soldiers or some of them stayed up there. I suppose, though, that all of them came away from there, as they would be afraid to stay if only a few remained. Not many people were in the lodges of our camp. Most of the women and children and old Cheyennes were gone to the west side of the valley or to the hills at that side. A few were hurrying back and forth to take away packs. My father was the only person at our lodge. I told him of the fight up the valley. I told him of my having helped in the killing of the enemy Indian and some soldiers in the river. I gave to him the tobacco I had taken. I showed him my gun and all of the cartridges. "You have been brave," he cheered me. "You have done enough for one day. Now you should rest." "No, I want to go and fight the other soldiers," I said. "I can fight better now, with this gun." "Your horse is too tired," he argued. "Yes, but I want to ride the other one." He turned loose my tired horse and roped my other one from the little herd being held inside the camp circle. He blanketed the new mount and arranged the lariat bridle. He applied the medicine treatment for protecting my mount. As he was doing this I was making some improvements in my appearance, making the medicine for myself. I added my sheathknife to my stock of weapons. Then I looked a few moments at the battling Indians and soldiers across the river on the hills to the northeastward. More and more Indians were flocking from the camps to that direction. Some were yet coming along the hills from where the first soldiers had stopped. The soldiers now in view were spreading themselves into lines along a ridge. The Indians were on lower ridges in front of them, between them and the river, and were moving on around up a long coulee to get be. hind the white men. "Remember, your older brother already is out there in the fight," my father said to me. "I think there will be plenty of warriors to beat the soldiers, so it is not needful that I send both of my sons. You have not your shield nor your eagle wing bone flute. Stay back as far as you can and shoot from a long distance. Let your brother go ahead of you." Two other young men were near us. They had their horses and were otherwise ready, but they told me they had decided not to go. I showed them my captured gun and the cartridges. I told them of the tobacco and the clothing and other things we had taken from the soldiers up the valley. This changed their minds. They mounted their horses and accompanied me. We forded the river where all of the Indians were crossing it, at the broad shallows immediately in front of the little valley or wide coulee on the east side. We fell in with others, many Sioux and a few Cheyennes, going in our same direction. We urged our horses on up the small valley. As we approached the place of battle each one chose his own personal course. All of the Indians had come out on horse. back. Almost all of them dismounted and crept along the gullies afoot after the arrival near the soldiers. Still, there were hundreds of them riding here and there all the time, most of them merely changing position, but a few of them racing along back and forth in front of the soldiers, in daring movements to exhibit bravery. I swerved up a gulch to my left, where I saw some Cheyennes going ahead of me. Other Cheyennes were coming here from the east side of the soldiers. Although it was natural that tribal members should keep together, there was everywhere a mingling of the fighters from all of the tribes. The soldiers had come along a high ridge about two miles east from the Cheyenne camp. They had gone on past us and then swerved off the high ridge to the lower ridge where most of them afterward were killed. While they were yet on the far-out ridge a few Sioux and Cheyennes had exchanged shots with them at long distance, without anybody being hurt. Bobtail Horse, Roan Bear and Buffalo Calf, three Cheyennes, and four Sioux warriors with them, were said to have been the first of our Indians to cross the river and go to meet the soldiers. [Note: according to Bobtailed Horse, who was there, one of these four Sioux warriors was White Cow Bull; see Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info.] Bobtail Horse was an Elk warrior, Roan Bear a Fox warrior, and Buffalo Calf a Crazy Dog warrior. They had been joined soon afterward by other Indians from the valley camps and from the southward hills where the first soldiers had taken refuge. Most of the Indians were working around the ridge now occupied by the soldiers. We were lying down in gullies and behind sagebrush hillocks. The shooting at first was at a distance, but we kept creeping in closer all around the ridge. Bows and arrows were in use much more than guns. From the hiding-places of the Indians, the arrows could be shot in a high and long curve, to fall upon the soldiers or their horses. An Indian using a gun had to jump up and expose himself long enough to shoot. The arrows falling upon the horses stuck in their backs and caused them to go plunging here and there, knocking down the soldiers. The ponies of our warriors who were creeping along the gulches had been left in gulches farther back. Some of them were let loose, dragging their ropes, but most of them were tied to sagebrush. Only the old men and the boys stayed all the time on their ponies, and they stayed back on the surrounding ridges, out of reach of the bullets. The slow long-distance fighting was kept up for about an hour and a half, I believe. The Indians all the time could see where were the soldiers, because the white men were mostly on a ridge and their horses were with them. But the soldiers could not see our warriors, as they had left their ponies and were crawling in the gullies through the sagebrush. A warrior would jump up, shoot, jerk himself down quickly, and then crawl forward a little further. All around the soldier ridge our men were doing this. So not many of them got hit by the soldier bullets during this time of fighting.

"Come. We can kill all of them." All around, the Indians began jumping up, running forward, dodging down, jumping up again, down again, all the time going toward the soldiers. Right away, all of the white men went crazy. Instead of shooting us, they turned their guns upon themselves. Almost before we could get to them, every one of them was dead. They killed themselves. The Indians took the guns of these soldiers and used them for shooting at the soldiers on the high ridge. I went back and got my horse and rode around beyond the east end of the ridge. By the time I got there, all of the soldiers there were dead. The Indians told me that they had killed only a few of those men, that the men had shot each other and shot themselves. [Note: click here for more info on American suicides at the Little Bighorn.] A Cheyenne told me that four soldiers from that part of the ridge had turned their horses and tried to escape by going back over the trail where they had come. Three of these men were killed quickly. The fourth one got across a gulch and over a ridge eastward before the pursuing group of Sioux got close to him. His horse was very tired, and the Sioux were gaining on him. He was moving his right arm as though whipping his horse to make it go faster. Suddenly his right hand went up to his head. With his revolver he shot himself and fell dead from his horse. I raced my horse to hurry around to the hillside north of the soldier ridge. The Indians there were all around a band of soldiers on the north slope. 4 I got off my horse and fired two shots, at long distance, with my soldier gun. I did not shoot any more, because the sagebrush was full of Indians jumping up and down and crawling close to the soldiers, and I was afraid I might hit one of our own men. About that time, all of this band of soldiers went crazy and fired their guns at each other's heads and breasts or at their own heads and breasts. All of them were dead before the Indians got to them. Many hundreds of boys on horseback were watching the battle. They were on the hills all around, far enough away to be out of reach of the soldier bullets. The ridge north of the soldier ridge was crowded with these boys and some old men. When the warriors were crowding in close to the soldiers on the north slope, one soldier there broke away and ran afoot across a gulch toward the northward hill. I suppose he thought there were no warriors in that direction, as all of them were hidden and creeping through the sagebrush and gullies. But several of them jumped up and ran after him. Just after he got across the gulch he stopped, stood still, and killed himself with his own revolver. A Cheyenne boy named Big Beaver lashed his pony into a dash down to the dead white man. The boy got the soldier's revolver and his belt of cartridges, jumped back upon his pony, and hurried away again to the hilltop. A Cheyenne warrior scalped the soldier and hung the scalp on a bunch of sagebrush, leaving it there. While I was at this part of the field, a Waist and Skirt Indian said to me: "I think I see the big chief of the soldiers. I have been watching one certain man who appears to be telling all of the others what to do." He tried to point out this man. But just then another bunch of soldier horses went running wildly among them, kicking up a great dust and knocking down or jostling the men. So I did not get to see the special man the Indian was trying to show me. I saw one Sioux walking slowly toward the gulch, going away from where were the soldiers. He wabbled dizzily as he moved along. He fell down, got up, fell down again, got up again. As he passed near to where I was I saw that his whole lower jaw was shot away. The sight of him made me sick. I had to vomit. I did not know him, and I did not learn whether he died or not.

I got down afoot in the gulch. I let out my long lariat rope for leading my horse while I joined the warriors creeping up the slope toward the soldiers. During all of the earlier fighting, when I had been most of the time going from place to place on horseback, I had fired several shots with my rifle captured from the soldier when we chased them across the river. I also had used my six-shooter. I had replaced the four bullets expended during the chase of the first soldiers in the valley. In this second battle I used up the six, reloaded the six-shooter, and fired all of these additional six shots at the soldiers. But it is hard to shoot straight when on horseback, especially when there is much noise and much shooting and excitement, as the horse will not stand still. When I went crawling up the slope I could lie down and shoot. I could not see any particular soldier to shoot at, but I could see their dead horses, where the men were hiding. So I just sent my bullets in that direction. A Sioux wearing a warbonnet was lying down behind a clump of sagebrush on the hillside only a short distance north of where now is the big stone having the iron fence around it. He was about half the length of my lariat rope up ahead of me. Many other Indians were near him. Some boys were mingled among them, to get in quickly for making coup blows on any dead soldiers they might find. A Cheyenne boy was lying down right behind the warbonnet Sioux. The Sioux was peeping up and firing a rifle from time to time. At one of these times a soldier bullet hit him exactly in the middle of the forehead. His arms and legs jumped in spasms for a few moments, then he died. The boy quickly slid back down into a gully, jumped to his feet and ran away. [Note: the Cheyenne boy who ran away was Big Beaver. Here is his account of the same moment in the battle.] A soldier on a horse suddenly appeared in view back behind the warriors who were coming from the eastward along the ridge. He was riding away to the eastward, as fast as he could make his horse go. It seemed he must have been hidden somewhere back there until the Indians had passed him. A band of the Indians, all of them Sioux, I believe, got after him. I lost sight of them when they went beyond a curve of the hilltop. I suppose, though, they caught him and killed him. The shots quit coming from the soldiers. Warriors who had crept close to them began to call out that all of the white men were dead. All of the In dians then jumped up and rushed forward. All of the boys and old men on their horses came tearing into the crowd. The air was full of dust and smoke. Everybody was greatly excited. It looked like thousands of dogs might look if all of them were mixed together in a fight. All of the Indians were saying these soldiers also went crazy and killed themselves. I do not know. I could not see them. But I believe they did so. Seven of these last soldiers broke away and went running down the coulee sloping toward the river from the west end of the ridge. I was on the side opposite from them, and there was much smoke and dust, and many Indians were in front of me, so I did not see these men running, but I learned of them from the talk afterward. They did not get far, because many Indians were all around them. It was said that these seven men, or some of them, killed themselves. I do not know, as I did not see them. 5 After the great throng of Indians had crowded upon the little space where had been the last band of fighting soldiers, a strange incident happened: It appeared that all of the white men were dead. But there was one of them who raised himself to a support on his left elbow. He turned and looked over his left shoulder, and then I got a good view of him. His expression was wild, as if his mind was all tangled up and he was wondering what was going on here. In his right hand he held his six-shooter. Many of the Indians near him were scared by what seemed to have been a return from death to life. But a Sioux warrior jumped forward, grabbed the six-shooter and wrenched it from the soldier's grasp. The gun was turned upon the white man, and he was shot through the head. Other Indians struck him or stabbed him. I think he must have been the last man killed in this great battle where not one of the enemy got away. This last man had a big and strong body. His cheeks were plump. All over his face was a stubby black beard. His mustache was much longer than his other beard, and it was curled up at the ends. The spot where he was killed is just above the middle of the big group of white stone slabs now standing on the slope southwest from the big stone. I do not know whether he was a soldier chief or an ordinary soldier. I did not notice any metal piece nor any special marks on the shoulders of his clothing, but it may be they were there. Some of the Cheyennes say now that he wore two white metal bars. But at that time we knew nothing about such things. One of the dead soldier bodies attracted special attention. This was one who was said to have been wearing a buckskin suit. I had not seen any such soldier during the fighting. When I saw the body it had been stripped and the head was cut off and gone. Across the breast was some writing made by blue and red coloring into the skin. On each arm was a picture drawn with the same kind of blue and red paint. One of the pictures was of an eagle having its wings spread out. Indians told me that on the left arm had been strapped a leather packet having in it some white paper and a lot of the same kind of green picture-paper found on all of the soldier bodies. Some of the Indians guessed that he must have been the big chief of the soldiers, because of the buckskin clothing and because of the paint markings on his breast and arms. 6 But none of the Indians knew then who had been the big chief. They were only guessing at it. The sun was just past the middle of the sky. 7 The first soldiers, up the valley, had come about the middle of the forenoon. The earlier part of the fighting against these second soldiers had been slow, all of the Indians staying back and approaching grad ually. At each time of charging, though, the mixup lasted only a few minutes.

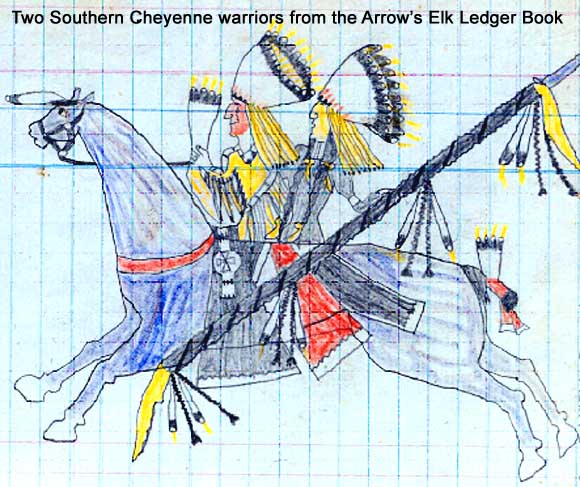

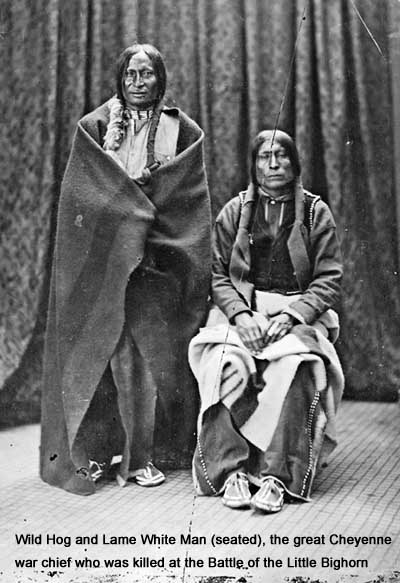

Somebody told me Noisy Walking was badly wounded. I went to where he was said to be, down in the gulch where the band of soldiers nearest the river had been killed in the earlier part of the battle. He was my same age, and we often had been com panions since our small boyhood. White Bull, an important medicine man, was his father. [Note: Noisy Walking was also the nephew of Kate Bighead.] I asked the young man: "How are you?" He replied: "Good." But he did not look well. He had been hit by three different bullets, one of them having passed through his body. He had also some stab wounds in his side. Word had been sent to his relatives in the camp west of the river, and it was said his women relatives were coming after him with a travois. I moved on eastward up the gulch coulee. I discovered almost hidden the dead body of an Indian. I did not go up close to it, but I could see the scalp was gone. That puzzled me. Could this be a Crow or a Shoshone? I had not known of there being any Indians belonging to these soldiers killed here. As I stood there looking, it seemed there was something familiar about the appearance of that body. I backed away and went to find my brother Yellow Hair. We two returned to the place. We got off our horses and walked to the dead Indian. We rolled the body over and looked closely. "Yes, it is Lame White Man," my brother agreed. We called other Cheyennes. Several of them came. All of them promptly confirmed our identification. All of us were satisfied some Sioux had scalped him, or maybe had killed him [Lame White Man], finding him in among the soldiers and supposing him to be a Crow or a Shoshone belonging to them. We knew he had gone with the young men in their charge upon the soldiers there. Perhaps he had gone farther than the others and was killed on his way back to us, the killer mistaking him for an attacking enemy Indian. A bullet had gone in at his right breast and out at his back. He also had many stab wounds. He was still dressed in his best clothing, none of it having been taken. The Cheyennes never made any inquiries among the Sioux concerning the case. We just kept quiet about it. My brother took the blanket from his horse and covered the body of the favorite Cheyenne warrior chief. A young man hurried away to go across the river and tell his people. When I came back to the place an hour or so afterward the dead man's wife and three or four women helpers had come with a horse dragging a travois. Four of us young men rolled the body into the blanket and put it upon the buffalo hide stretched across the lodgepoles. The women set off with it toward the river. I helped likewise in putting my friend Noisy Walking upon the swinging bed when his father and mother and other women came after him. Judging by his appearance then, this was the last good act I ever should do for him. Various groups of women, many more of the Sioux than of the Cheyennes, were on the field searching for and taking away their dead and wounded men. Two Sioux had been killed in this same first charge upon the soldiers. I did not like to hear the weeping of the women. My heart that had been glad because of the victory was made sad by thoughts of our own dead and dying men and their mourning relatives left behind. I noticed decorations on the shoulders and stripes on the arms of some of the soldier coats. I did not think of their meanings. I did not hear any of the Indians there talk about any meanings for these special marks. If I thought about it at all, I may have thought these were particular medicine ways the soldiers had for preparing themselves. It was a long time after that day before I learned that the wearers of these were the soldier chiefs. Each Indian horse used for going into the battle had only a blanket strapped upon its back and a lariat rope about the neck. In riding, the lariat was looped into the horse's mouth, or was looped over the head and then into the mouth, for a bridle. The surplus of the long rope was coiled and tucked into the rider's belt. If a man fell from his horse the coil would be jerked from his belt, so he would not be dragged. Also, the uncoiling as the horse might move away would leave a long rope trailing after it, so it was easy to recapture the animal. That was the regular Indian way of riding. Warbonnets were worn by twelve Cheyennes among the three hundred or more of our warriors in the battle. It may be I have forgotten a few of them, but as I recollect it our warbonnet men on that day were these: 9 Crazy Head, Crow Necklace, Little Horse, Wolf Medicine, White Elk, Howling Wolf, Braided Locks, Chief Coming Up, Mad Wolf, Little Shield, Sun Bear and White Body. Three of these were little warrior chiefs. Ten of the warbonnets had trails. Sun Bear had a single buffalo horn projecting out from the front of his forehead band. Crazy Head was a big chief of the tribe, had been a great fighter in past times, but was not now a warrior chief. While he had on his warbonnet here, I suppose he stayed in the background and let the young men do the fighting. Chief Lame White Man was not wearing a warbonnet on this occasion. It was not usual for a man of his high standing to go into the battle as he did. I suppose he did so because he had not there any son to serve as a warrior. Not any Cheyenne fought naked in this battle. All of them who were in the fight were dressed in their best, according to the custom of both the Cheyennes and the Sioux. Of our warriors, Sun Bear was nearest to nakedness. He had on a special buffalo-horn head-dress. I saw several naked Sioux, perhaps a dozen or more. Of course, these had special medicine painting on the body. Two different Sioux I saw wearing buffalo head skins and horns, and one of them had a bear's skin over his head and body. These three were not dressed in the usual war clothing. It is likely there were others I did not see. Perhaps some of the naked ones were No Clothing Indians. A dead Uncpapa Sioux received something of the same kind of mistaken attention given to our Lame White Man. The dead Sioux was mixed in with dead bodies of the soldiers. An Arapaho and a No Clothing Indian supposed him to be a Crow or a Shoshone belonging to the white men fighters. They jabbed spears many times into the body. They were much embarrassed when they learned of their mistake. I found a metal bottle, as I was walking among the dead men. It was about half full of some kind of liquid. I opened it and found that the liquid was not water. Soon afterward I got hold of another bottle of the same kind that had in it the same kind of liquid. I showed these to some other Indians. Different ones of them smelled and sniffed. Finally a Sioux said: "Whisky." Bottles of this kind were found by several other Indians. Some of them drank the contents. Others tried to drink, but had to spit out their mouthfuls. Bobtail Horse got sick and vomited soon after he had taken a big swallow of it. It became the talk that this whisky explained why the soldiers became crazy and shot each other and themselves instead of shooting us. One old Indian said, though, that there was not enough whisky gone from any of the bottles to make a white man soldier go crazy. We all agreed then that the foolish actions of the soldiers must have been caused by the prayers of our medicine men. I believed this was the true explanation. My belief became changed, though, in later years. I think now it was the whisky. 10 I took a folded leather package from a soldier having three stripes on the left arm of his coat. It had in it lots of flat pieces of paper having pictures or writing I did not then understand. The paper was of green color. I tore it all up and gave the leather holder to a Cheyenne friend. Others got packages of the same kind from other dead white men. Some of it was kept by the finders. But most of it was thrown away or was given to boys, for them to look at the pictures. 11 I rode away from the battle hill in the middle of the afternoon. Many warriors had gone back across the hills to the southward, there to fight again the first soldiers. But I went to the camps across on the west side of the river. I had on a soldier coat and breeches I had taken. I took with me the two metal bottles of whisky. At the end of the arrow shaft I carried the beard scalp. I waved my scalp as I rode among our people. The first person I met who took special interest in me was my mother's mother. She was living in a little willow dome lodge of her own. "What is that?" she asked me when I flourished the scalp stick toward her. I told her. "I give it to you," I said, and I held it out to her. She screamed and shrank away. "Take it," I urged. "It will be good medicine for you." Then I went on to tell her about my having killed the Crow or Shoshone at the first fight up the river, about my getting the two guns, about my knocking in the head two soldiers in the river, about what I had done in the next fight on the hill where all of the soldiers had been killed. We talked about my soldier clothing. She said I looked good dressed that way. I had thought so too, but neither the coat nor the breeches fit me well. The arms and legs were too short for me. Finally she decided she would take the scalp. She went then into her own little lodge. I passed one bottle of the whisky among friends. Each took a small drink of it until all of it was gone. The other bottle I gave to Little Hawk. He himself drank all of the whisky in it. Pretty soon, though, he became sick and he vomited up everything in his stomach. Some special excitement was going on over beyond the Arrows All Gone camp. A big crowd of Sioux were gathered there. I went to see what they were doing. They had surrounded some Indians just then arrived in the camp. "Kill them, every one of them," some Sioux were shouting. Others were say ing: "Wait. Let us be sure." Above the confusion of threats and general noise of the excited throng I heard an angry thundering:

It was the voice of Little Wolf, most respected of '' the four old men chiefs of the Cheyennes. He was speaking in our language. He could not talk Sioux. He never had mingled much with them, so not many of them knew him. Yellow Horse, an old Southern Cheyenne man, was with me. He said to me: "Let us go to Little Wolf. You are his relative, you know the Sioux language, and you should talk for him." We crowded our way through to the old chief. Both of us shook hands with him. The Sioux began talking to us about him. Some Cheyennes also were accusing him. One of these was White Bull. He knew Little Wolf, but he said the chief ought to have been with the Cheyennes long ago, that he ought not to have waited until after the fighting before joining us, that he stayed too long on the reservation. I knew that White Bull's heart was troubled, though, about his own son, Noisy Walking. Finally, Yellow Horse called out: "Wait until this young man talks to Little Wolf. He will find out and tell everybody." "Have you been with the soldiers?" I asked the chief. "No, you foolish boy," he flared back at me. "Do these people think I am a crazy man? I have with me seven lodges of our people. There are families of women and children. They have their tepees, their packhorses, all of their property. Does any. body suppose that is the way to join the soldiers and help them? Not any part of me ever was white man. I am all Indian. I am willing to fight any man who says I am not." He went on to tell all about the experiences of his little band of Cheyennes. On their way out from the reservation they saw soldiers camped on the upper Rosebud, just the afternoon before. They kept hidden back in the hills and watched the soldiers go on toward the divide leading to the Little Bighorn. His people did not set up their lodges that night. Instead, they traveled a while and rested a while, their scouts all the time watching the soldiers. Early in the morning, some of Little Wolf's young men out in front found a box of something the soldiers had lost. Just then, some soldiers came back, shot at these young men, and they returned to Little Wolf. 12 The band continued to follow the soldiers, but kept themselves hidden. From the hilltops they heard the guns and saw some of the fighting. It appeared that all of the Indians in the camps were running away. Finally, the shooting mostly died down. The frightened little band peeped over the hilltops and saw that the camps and the Indians still were on the valley. Then they cautiously came on to join us. I repeated all of this story to a Sioux chief. He told the assembled Sioux warriors and I told the Cheyennes. Some grumbling continued, many saying that Little Wolf ought to have been with us long ago, but all of them became satisfied that neither he nor his companions deserved killing. The crowd scattered, and the newcomers moved on to join the Cheyenne camp. There were some additional scoldings of them on account of their having stayed so long at the reservation. But their women had plenty of sugar and coffee in their packs, and with gifts of these desirable extra foods they soon quieted all complaints. Little Wolf at that time was fifty-five years old. Burial parties of Cheyennes were going to the hill gulches west of our camps, to put our dead into rock crevices. Each warrior lost was disposed of by his women relatives and his young men friends. A big band of people went out to help bury Lame White Man. I accompanied the relatives of Limber Bones, one of our young men who had been killed. We took him far back up a long coulee. We found there a small hillside cliff. Four of us young men helped the women to clear out a sheltered cove. In there we placed the dead body, wrapped in blankets and a buffalo robe. We piled a wall of flat stones across the front of the grave. His mother and another woman sat down on the ground beside it to mourn for him. The rest of us returned to the valley. The Sioux likewise were disposing of their dead. Their customary way was to set up burial tepees. It appeared that in all of the Sioux camps these were being set up. They were placed where had been the dwelling lodges, or near them. In some cases the original dwelling lodges of the dead ones were left standing, in each case the body being all dressed for burial and left on a scaffold in the lodge or on the dirt floor, the dwelling being then abandoned by the inhabitants. This was a common mode of Sioux burial, and sometimes the Cheyennes did it in this way. All of the camps were being moved. This was in accordance with a regular custom among the Indian tribes. When any death occurred in a camp, either from battle or from other cause, right at once the people began to get ready to move camp to some other place. The Cheyennes selected a camping spot down the river about a mile northwestward. The Sioux all began moving northwestward and back from the Little Bighorn toward the base of the bench hills west from the river. In the new locations, all of the camps except the Cheyennes were west of the present railroad and highway. Most of the women and children and older people in the camps had fled toward the hills to the northward and westward when the first band of soldiers made the attack upon the Uncpapas at the upper part of the group of camps. I suppose there were very few people left in the camps at that end until after those soldiers had been chased away and across the river. When I rode up there and around the west and south sides of the Uncpapa and Blackfeet circles it was hard to keep from running over the Indians who were hurrying afoot toward the bench lands to the westward. Our Cheyenne people who were not active warriors started to go toward the north, down the valley, and some of them crossed the river. But when the second band of soldiers were seen on the high ridge far out eastward these Cheyennes who had crossed the river returned to the camping side. Of course, nobody knew how many soldiers were coming. Nobody knew what would be the outcome of their attack. They had surprised us by their sudden appearance. We were not prepared for battle. At the first time of the flight from the camps, many women and some of the men seized small packs of food or other precious possessions and carried them away. The fleeing ones stopped on the benchlands west of where had been their camp circles. They stayed there and watched the fighting. After a little while, since no more of the soldiers had come to that side of the river, people began hurrying to the camps, quickly gathering up other things, then hurrying back to the hilltops. Later, as none of our warriors were returning, it became evident that we were winning the contest. Our people then became more confident. The old men who were making medicine prayers for our success added words of encouragement to the waiting families. Throngs of women now were busy going back and forth between the old and the new camp positions. They were carrying water from the river and wood from the timber. All of the lodges not abandoned were taken down. Most of them were packed, not set up in the new spots of location. The poles were wrapped, the buffalo skin coverings were put into bundles, packs were made up, all put into readiness for quick movement elsewhere if need be. Only the cooking pots and other essential articles were left in use. The women went by hundreds to cut willows for making little skeleton dome shelters, in substitution for the regular tepee lodges kept packed. It had not rained here during all of that day, but rain might come at any time. Not all of the Indians, though, prepared shelters. Many depended only upon robes for shielding them if shielding should become needful. The lodges of mourning Cheyennes were torn or cut to pieces or burned, and their furnishings were cast away. These bereft people, according to our customs, now had to live during their time of mourning without any lodge or any property of their own. They dwelt outside or with hospitable friends. The poles and skins of any travois used to carry dead bodies were also thrown away. Sometimes the horses used to drag the travois of a dead person were killed or were turned loose to be captured by whoever might want them. After sundown I visited Noisy Walking. He was lying on a ground bed of buffalo robes under a willow dome shelter. His father White Bull was with him. His mother sat just outside the entrance. I asked my friend: "How are you?" He replied: "Good, only I want water." I did not know what else to say, but I wanted him to know that I was his friend and willing to do whatever I could for him. I sat down upon the ground beside him. After a little while I said: "You were very brave." Nothing else was said for several minutes. He was weak. His hands trembled at every move he made. Finally he said to his father: "I wish I could have some water -- just a little of it." "No. Water will kill you." White Bull almost choked as he said this to his son. But he was a good medicine man, and he knew what was best. As I sat there looking at Noisy Walking I knew he was going to die. My heart was heavy. But I could not do him any good, so I excused myself and went away. There was no dancing nor celebrating of any kind in any of the camps that night. Too many people were in mourning, among all of the Sioux as well as among the Cheyennes. Too many Cheyenne and Sioux women had gashed their arms and legs, in token of their grief. The people generally were praying,.not cheering. There was much noise and confusion, but this was from other causes. Young men were going out to fight the first soldiers now hiding themselves on the hill across the river from where had been the first fighting during the morning. Other young men were coming back to camp after having been over there shooting at these soldiers. Movements of this kind had been going on all the time since the final blows fell upon all of the soldiers in the second and greatest battle. Old men heralds were riding about all of the camps, singing the braveheart songs and calling out: "Young men, be brave." The only fires anywhere among us were little camp fires for cooking. Or, there may have been at times a larger blaze coming from some mourning family's lodge being burned. I did not go back that afternoon nor that night to help in fighting the first soldiers. Late in the night, though, I went as a scout. Five young men of the Cheyennes were appointed to guard our camp while other people slept. These were Big Nose, Yellow Horse, Little Shield, Horse Road and Wooden Leg. One or other of us was out somewhere looking over the country all the time. Two of us went once over to the place where the soldiers were hidden. We got upon hill points higher than they were. We could look down among them. We could have shot among them, but we did not do this. We just saw that they yet were there. Five other young men took our duties in the last part of the night. I was glad to be relieved. I did not go to my family group for rest. I let loose my horse and dropped myself down upon a thick pad of grassy sod. Dr. Thomas B. Marquis's Footnotes:1 Little Sun, in the presence of Wooden Leg and other veteran Cheyennes, told me of this incident.-T. B. M. 2 This apparently was Bloody Knife, Custer's favorite Arikara scout.-T. B. M. 3 The Indians differ as to the color of the horses ridden by these soldiers, but military students of the case believe this to have been Lieutenant Smith's troop.-T. B. M. 4 Captain Keogh or Captain Tom Custer, or both troops: T. B. M. 5 The story of wholesale suiciding is such a reversal of our accepted conceptions that some reader may exclaim: "That is a villifying falsehood!" But it is the truth. Most of the Seventh cavalry enlisted men on that occasion were recent recruits. Only a few of them ever had been in an Indian battle, or in any kind of battle. It is evident, though, that they fought well through an hour and a half or two hours. Then, finding themselves vastly outnumbered, they "went crazy," as the Indians tell. They put into panicky practice the old frontiersman rule, "When fighting Indians keep the last bullet for yourself." A great mass of circumstantial evidence supports this explanation of the military disaster. The author hopes to attain publication, at some future time, of his own full analysis of the entire case, -T. B. M. 6 Evidently this was Captain Tom Custer.-T. B. M. 7 All old Cheyennes insist the battle ended about noon.-T. B. M. 8 This unfortunate soldier probably was Lieutenant Cook: T. B. M. 9 Various old Cheyennes helped Wooden Leg in making this list.T. B. M. 10 The whisky explanation is regularly advanced by the warrior veterans nowadays. It appears none of them have any conception of suicide to avoid capture.-T. B. M. 11 Paper money. The soldiers received two months' pay after they had left Fort Lincoln. There had been no opportunity for them to spend a cent, except among themselves, since that time.-T. B. M. 12 Here appears to have been the key incident that misled Custer into supposing his presence revealed to the camps and that caused him to attack at once, lest they escape. Big Crow, Black Horse and Medicine Bull, all of them with the Little Wolf band, told me the details of this experience.-T. B. M. Wooden Leg: A Warrior Who Fought Custer by Dr. Thomas B. Marquis, The Midwest Co., Minneapolis, MN 1931, p 217- 257

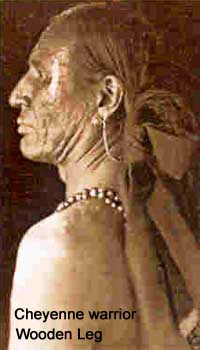

By almost any measure, A Warrior Who Fought Custer is the single most impressive Native American account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Here is Wooden Leg's account of the Battle of the Rosebud.

|

|

|||||||||||

IN MY SLEEP I dreamed that a great crowd of people were making lots of noise. Something in the noise startled me. I found myself wide awake, sitting up and listening. My brother [Yellow Hair] too awakened, and we both jumped to our feet. A great commotion was going on among the camps. We heard shooting. We hurried out from the trees so we might see as well as hear. The shooting was somewhere at the upper part of the camp circles. It looked as if all of the Indians there were running away toward the hills to the westward or down toward our end of the village. Women were screaming and men were letting out war cries. Through it all we could hear old men calling:

IN MY SLEEP I dreamed that a great crowd of people were making lots of noise. Something in the noise startled me. I found myself wide awake, sitting up and listening. My brother [Yellow Hair] too awakened, and we both jumped to our feet. A great commotion was going on among the camps. We heard shooting. We hurried out from the trees so we might see as well as hear. The shooting was somewhere at the upper part of the camp circles. It looked as if all of the Indians there were running away toward the hills to the westward or down toward our end of the village. Women were screaming and men were letting out war cries. Through it all we could hear old men calling:

I had remained on my horse during most of the long time of the fighting at a distance. I rode from place to place around the soldiers, keeping myself back, as my father had urged me to do, while my older brother crept close with the other warriors. I got off and crept with them, though, for a little while at the place where the band of soldiers rode down toward the, river. After they were dead I got my horse and mounted again. I stayed mounted until I got around into the gulch north from the west end of the soldier ridge. By this time all of the soldiers were gone except a band of them at the west end of the ridge. They were hidden behind dead horses. Hundreds or thousands of warriors were all around them, creeping closer all the time. From the gulch where I was I could see the north slope of the ridge covered by the hidden Indians. But the soldiers, from where they were, could not see the warriors, except as some Indian might jump up to shoot quickly and then duck down again. We could get only glimpses of the soldiers, but we knew all the time right where they were, because we could see their dead horses.

I had remained on my horse during most of the long time of the fighting at a distance. I rode from place to place around the soldiers, keeping myself back, as my father had urged me to do, while my older brother crept close with the other warriors. I got off and crept with them, though, for a little while at the place where the band of soldiers rode down toward the, river. After they were dead I got my horse and mounted again. I stayed mounted until I got around into the gulch north from the west end of the soldier ridge. By this time all of the soldiers were gone except a band of them at the west end of the ridge. They were hidden behind dead horses. Hundreds or thousands of warriors were all around them, creeping closer all the time. From the gulch where I was I could see the north slope of the ridge covered by the hidden Indians. But the soldiers, from where they were, could not see the warriors, except as some Indian might jump up to shoot quickly and then duck down again. We could get only glimpses of the soldiers, but we knew all the time right where they were, because we could see their dead horses.

"No. I had nothing to do with the soldiers. I am all Indian, all Cheyenne."

"No. I had nothing to do with the soldiers. I am all Indian, all Cheyenne."