|

||||||||||

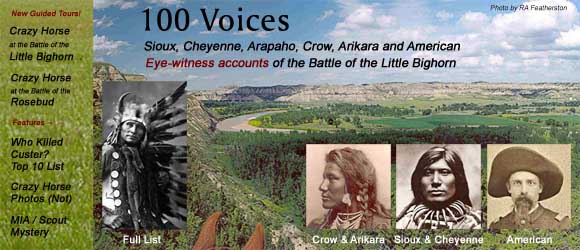

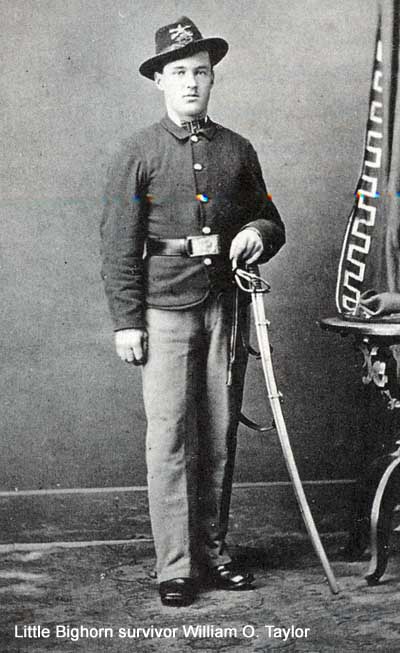

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... William O. Taylor's Story of the Battle

WILLIAM O. TAYOR'S STORY OF THE BATTLE

The spot that had been chosen for our bivouac was one of the most beautiful that we had met with. On our right rose a high, and for a short distance almost perpendicular bluff, between which and the river, a clear, cool, running stream, was a level grassy plateau some two hundred yards wide. Over which was scattered in great profusion masses of wild rosebushes in full bloom, with here and there a tree to add to the park like effect. It was easy to see why the river was given its name, fringed as it was with low willows and fragrant rosebushes, it was such a place for a camp that Custer was in the habit of selecting when possible one of great natural beauty. In this case it seemed so very fitting that what was to prove to be the "last camp" for so many should be such a beautiful place. I have often wished since that time that the spot might be located and a photograph obtained. But to continue, my Troop [A] was quite near to Custer's headquarters, a single "A" tent, before which he sat for a long time alone and apparently in deep thought. I was lying on my side, facing him, and was it my fancy, or the gathering twilight that made his face take on an expression of sadness that was new to me. [Note: Edward Godfrey shared this perception about Custer]. Was it because his thoughts were far away, back to Fort Lincoln where he had left a most beloved wife, and was his heart filled with a premonition of what was to happen on the morrow? His reverie however was soon broken by the gathering of a number of officers at his tent for certain instructions. As the council broke up a small group of the younger officers stopped near the bivouac of one of their number and soon the words of "Annie Laurie", with a slow sad cadence came to my ears, followed shortly by "Little Footsteps, Soft and Gentle", and then, "The Good Bye at the Door", ending with the "Doxology: Praise God From Whom all Blessings Flow ", a rather strange song for Cavalrymen to sing on an Indian trail. Was it not something in the nature of a prayer coming from the hearts of those young officers, several of them but a short time from West Point? May it not have been born of an unconscious premonition of the sad fate that so soon awaited many of them? But as the last words died away, as if to throw off their gloomy feelings they added "For He's a Jolly Goodfellow, That Nobody Can Deny; " rather irreverent it seemed to me at the time, but then reverence, of a religious nature, is not altogether a soldier's characteristic. A few "good nights" and they sought their rest. An unusual quietness settled over the camp, broken only by the stamping of a horse or the note of some night bird. As we lay there in that lovely and quiet bivouac, in a section of "the Indian's Paradise land," where we had never been before, how little could anyone think that a fierce battle had taken place only a short distance above us and just a week before when Crazy Horse stopped the advance of General Crook with a much larger force than our own. Nor could the strongest imagination foresee that in a little over a month the same hostiles we were then pursuing, flushed with another and far greater victory, could again be camping here on this beautiful stream, only to be hurried away by the close approach of General Terry from the north over the very trail we had just made and the second appearance of General Crook coming down the river from the south. How could we dream that the command now in camp was to encircle a large section of the country and come back to the same spot after the same hostile force we were now pursuing, or that, within a few miles of where we lay, the brave and unconquered "Lame Deer" would soon give up his life for the right to live and hunt along this rose-bordered stream, and his name, to the agency, set apart in after years, to his tribesmen. * * * OUR REST here proved to be but for a few hours only, for about ten o'clock we were awakened and ordered to saddle up for a night march. We were soon in the saddle and, still following the Rosebud, marched some ten miles or more ascending the north fork of the river up the divide separating the Rosebud from the Little Bighorn. We halted somewhere about 2 a.m. awaiting news from the scouts who had been sent ahead to locate, if possible, the camp of the Indians. Saddles were removed and many of the men availed themselves of the chance for a nap. After daylight came some coffee was made but the water was very poor and it was hard to drink it. Those who did not care to sleep sat around in little groups discussing the prospects of a fight and pulling away at the ever present pipe. General Custer who had gone on ahead to the point on the divide from whence the scouts had seen the smoke rising from the Indian village and the pony herds grazing in the valley near it, some twelve or fifteen miles away, had returned, and a little before eight o'clock came riding bareback, and I think also bareheaded, around to the several troops giving the officers the information that the Indians had been located, and saying that the command would move at once. The men began to saddle up and we were soon in motion travelling up the divide between the Rosebud and Little Bighorn rivers. We did not stop until about 10:30 a.m. when we came to a halt in a ravine, some four or five miles perhaps from the summit of the divide. Here we were ordered to keep concealed, and to preserve quiet. Captain Godfrey says, "It was Custer's declared intention not to attack until the next morning". But in the meantime our presence having been discovered, so the scouts and the others reported, "it was necessary to act at once," and we started off again crossing the divide a little before noon.

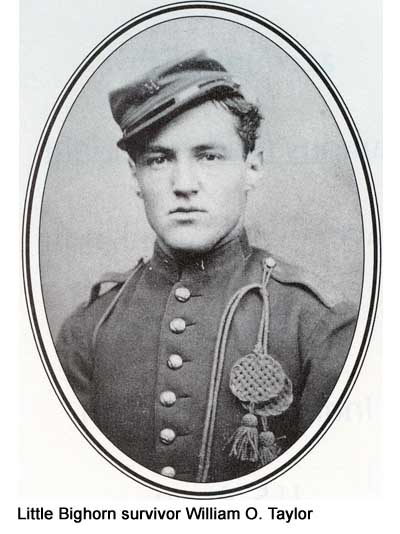

Captain Benteen's Battalion, consisting of troops D, H, and K, about 125 men, moved off to our left front, while General Custer with troops C, E, F, J, and L, were on our right. the pack-trains, with Captain McDougal and B troop as escort bringing up the rear. * * * Major Reno's Battalion, following the Indian trail, marched down a valley through which ran what has since been called Benteen's, or Sundance Creek. This creek flowed into the Little Bighorn river, when there was any water in it, but at this time it was dry. On our way we passed a funeral tepee, which contained the body of a warrior. The tepee had been set on fire by some of our Indian scouts. Afterwards it was learned that the dead warrior was a brother of Circling Bear [Old She Bear] and had been killed in the battle with Crook on the Rosebud, June 17th, eight days before. It has been stated that "a few Indians were seen near here," and that they kept far enough in advance to be out of danger. As to that I can not say, personally I did not see any of them. When, within a short distance of the river, Reno received an order that caused us to increase our speed and we soon came to the Little Bighorn, a stream some fifty to seventy feet wide, and from two to four feet deep of clear, icy cold water. Into it our horses plunged without any urging, their thirst was great and also their riders. While waiting for them to drink I took off my hat and, shaping the brim into a scoop, leaned over, filled it and drank the last drop of water I was to have for over twenty-four long hours. The horses having been watered, we rode out of the river and through the underbrush and then a few yards on the prairie, where we dismounted and tightened our saddle girths, and in about ten minutes were heading down a long but rather narrow valley. On our right was the heavily wooded and very irregular course of the river, flanked by high bluffs. On our left were low foothills near which we could see a part of the pony herds, and as we came nearer, could distinguish mounted men riding in every direction, some in circles, others passing back and forth. They were gathering up their ponies and also making signals. We were then at a fast walk. Soon the command was given to "trot". Then as little puffs of smoke were seen and the "Ping" of bullets spoke out plainly, we were ordered to charge.

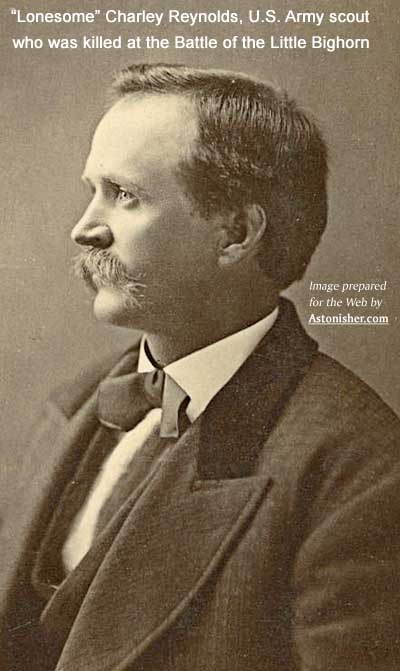

The Major and Lieutenant Hodgson were riding side by side a short distance in the rear of my Company. As I looked back Major Reno was just taking a bottle from his lips. He then passed it to Lieutenant Hodgson. It appeared to be a quart flask, and about one half or two thirds full of an amber colored liquid. There was nothing strange about this, and yet the circumstances remained indelibly fixed in my memory. I turned my head to the front as there were other things to claim my attention. What that flask contained, and effect its contents has, is not for me to say, but I have ever since had a very decided belief. [Note: this is the only eye-witness evidence (inference, actually) from an American source that Reno and other Seventh Cavalry officers were drinking alcohol as they entered the battle on June 25, 1876, but many Indians -- including Lazy White Bull, Soldier Wolf, Hollow Horn Bear and Iron Hawk -- said the American troopers acted "drunk," and Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg said he gave some of the whiskey he found on dead Seventh Cavalry soldiers to his friend Little Hawk, who drank some and got sick.]

But to resume, the river as I have already said, was a very tortuous one, and at this point it came well out into the prairie, made a sharp turn and then went back to the bluffs. It was lined on both sides by tall cottonwood trees, and its banks, thick with underbrush so that it shut off the view of the nearest part of the Indian Village which we were fast approaching. Over sage and bullberry bushes, over prickly pears and through a prairie dog village without a thought we rode. A glance along the line shows a lot of set, determined faces, some of them a little pale perhaps, but not altogether with fear. The Death Angel was very near. Was he putting his seal on those who inside of an hour would be lying on the prairie or in the woods, dead, stripped and gashed almost beyond recognition? Be that as it may, there was no flinching on the part of anyone. To most of us it was our first real battle at close range. Our baptism of fire, a new and strange experience, to sit up as a human target, to be shot at and not to return the fire, was a little trying, but our turn was at hand. "Halt!", came the sharp, quick order, "Prepare to fight on foot", follows at once. Every fourth man from the right remained in his saddle, the others dismounted and tying their horse together, handed the bridle reins to the number four man and sprang forward to their places in the skirmish line. When I look back and think of the sublime audacity of one hundred and fifty Cavalrymen charging with a cheer down on an Indian village that contained at least, twenty-five hundred Sioux warriors, and when within close range, dismounting to fight on foot leaving one fourth of their number to hold the horses, it does seems indeed like madness, one hundred fifty men to charge on a village of 1800 lodges. [Note: this is a pretty good estimate for the lodge count. General Terry's engineer officer counted 1800 lodge sites after the battle, and He Dog estimated there were 2000 lodges in the huge village. However, Taylor's figures for the American soldiers with Reno is high by a long shot. According to his own report, Reno actually commanded 112 horsemen, not 150, as Taylor states, so the odds against Reno, Taylor and the rest of Reno's men were even steeper than Taylor supposed, approaching 15-to-1, by the scouting information Custer received before the battle.]. The led horses, under the charge of Lieutenant Hare, were then taken into the woods for greater safety, keeping slightly in rear of the skirmish line. Just how long we remained there I can not say, but I shall never believe that it was over fifteen or twenty minutes at the most. I did not see Major Reno while in the woods nor do I recall hearing any commands as to what we should do. Noise there was aplenty and a few shots went whistling through the underbrush. All at once the skirmishers came rushing into the woods seeking their horses which they could not locate at first owing to the underbrush, and a slight change of position. Then I heard someone say, "We must get our of here, quick!" Number one and two of my set of four saw me and at once took their horses, leaving me with Con Crowley's horse, and wondering where he was. I soon espied him at a little distance rushing around and shouting "Where's my horse, Where's my horse?" I yelled at him, perhaps not politely, but effectively, for he hastened toward me. I threw him the bridle-rein and turned my horse in the direction I had seen the men going. All was in the greatest confusion and I dismounted twice and mounted again, all in a few moments, but why, I do not know, unless it was because I saw the others do it and thought they had orders to. Before I had gone many yards, I looked to my left and rear and saw quite a number of mounted Indians rushing through the woods in the same general direction we were going, as if they were trying to cut off the men who had preceded me. [Note: This may be a descriptions of Crazy Horse's flanking charge against Reno's defensive line in the timber, which began the killing rout of the Americans.] They were so near that my first thought was that they were some of our Indian scouts, but a second look undeceived me. For these Indians were mostly stripped to their fighting costume, a breech-clout at one end, a feather at the other, a whip hanging from their wrist and a gun in their hand. There was one exception however, a sturdy looking chap who was the nearest of all. He wore a magnificent war bonnet of great long feathers encircling his head and hanging down his back, the end trailing along the side of his pony. I did want to take a shot at him but the trees were close together, and I was not a very good marksman. Besides, my comrades seemed bent on getting out of there as soon as possible. So I let him live; I have often wondered since then if that fellow was not one of the, "Big Chiefs", Gall, or Black Moon. However, I continued on my way. The underbrush was very thick and in breaking my way through it my right stirrup was caught and the strap that attached it to the saddle was torn nearly off, so much so that the stirrup was useless and I had to be very careful of my balance. In far less time than it has taken to write this, I emerged from the woods, climbed up a little bank and came out on the prairie a short distance from where we first entered the woods.

On my left was a line of comrades headed due east toward the bluffs, which were one half to three-fourths of a mile away and at the base of which flowed the river, its banks at this point being high and precipitous and more or less fringed with a thick growth of underbrush. The situation was most serious, it was so sudden and incomprehensible. A few moments before, we were "driving the Indians with great ease." [Reno's Report.] Now we were the driven, but there was no time for speculation. [Note: actually, the sudden reversal of the Americans' situation was not "incomprehensible" at all. The Americans' surprise attack had sucker-punched a vastly larger and superior force, and so it is not suprising that the Americans' advance only carried them a short ways before the dire reality of their situation began to forcibly assert itself, especially since Reno did not receive the support Custer promised. See Who Killed Custer - The Eye-Witness Answer for more info]. Each man ahead of me had his right arm extended firing his revolver at a parallel line of yelling Indians and I at once followed suit. Talk about the "Thin Red Line" of the English. Here was a thick Red line of Sioux and growing thicker every moment. Out of the clouds of dust, anxious to be in at the death, came hundreds of others, shouting and racing toward the soldiers, most of whom were seeing their first battle, and many, of whom I was one, had never fired a shot from a horse's back. As before stated, my right stirrup was useless and in consequence my seat was not very secure, nor my aim as accurate as it might have been, so I can not say that I did much execution, but I tried to, firing at an Indian directly opposite who I thought was paying special attention to myself. At such a time many thoughts will pass through one's mind with great rapidity. The chances of being wounded or captured were many. One's fate in such a case was easy to imagine, so I reserved one of the six bullets that my revolver contained for the "last resort," myself, but I was not destined to use it in that manner. A great part of our way lay through a prairie-dog village and the numerous holes and mounds made it very unpleasant riding at our rapid gait, for you could not tell what moment your horse might put his foot in a hole and throw you to the ground. A few moments of such riding brought me to what had been, ages ago, the bed of the river. It was some three or four feet lower with a rather abrupt bank down which with a little urging my horse jumped. And as he did so, to steady myself, I reached for the pommel of my saddle with my right hand which still held my revolver. As I did this my revolver fell to the ground, the Indians were crowding in closer, for as they afterwards said "they thought to drive us all into the river and drown us," and I deemed it very unwise to dismount and look for it in the tall grass and weeds. So I hastened along to the river in which I saw a struggling mass of men and horses from whom little streams of blood was coloring the water near them. Lieutenant Hodgson was one of the number and had just been wounded, so I heard him say. I turned my horse a little to the right to avoid the crowd and, jumping him into the river, was soon across. After a hard struggle I climbed the steep bank, the rapid pace and exertion over the river had completely exhausted my horse and he stood trembling with fatigue and refused to go any further. He was a poor, broken winded beast at the best, and was to have been condemned long ago but a shortage of mounts made it necessary to take him along. As I was a late comer in that Troop, he was assigned to me, and bore the name of Steamboat, because of the particular noise he made when traveling. I dismounted and amid whistling of bullets stood there for a few moments waiting for him to get his breath. Then I tried to lead him along but he would not budge a foot. Getting in his rear, I jabbed him with my gun in vain while my comrades were rushing by the bluffs, some mounted, others on foot leading their horses, disappearing over the top. Things looked serious indeed, for to be dismounted in the face of hundreds of Sioux warriors but a short distance away, was like looking into your grave. In my anger and disgust I gave the beast a parting kick, unslung my carbine and started up the bluff, a mark as I thought for hundreds of rifles, little puffs of dust rising from the ground all around as the bullets buried themselves in the dry dusty hillside. The slope which we were ascending was a funnel shaped ridge, the small end being near the top of the bluff, with narrow, deep ravines on either side terminating within a few yards of the river. It must have been providence that directed us to that particular spot for there was no other place anywhere near that we could have made the ascent with so much haste and so little trouble. I had gone perhaps one third of the way up when I was overtaken by a dismounted comrade of my old Troop, [M] named Myers, "Tinker Bill" we used to call him from the fact of his having been a tinner's apprentice before his enlistment. We walked along quite close together for a few feet when with but the single exclamation of "Oh," Myers pitched forward face down to the ground. I bent over him but he was dead, shot between the left ear and eye. It may be my turn next I thought and instead of keeping straight ahead I bore off to the right a little and more into the ravine. Then turned again to the left, zig-zagging as it were but ever going up. When, within a short distance of the top, I was overtaken by a former comrade of M Troop, Frank Neeley. He was mounted and had a led horse with him. This horse he turned over to me, very glad to get rid of his charge. It was with a deep feeling of relief that I got into a saddle again for my chances were a little better now, although my new mount was not such a very great improvement over the one I had left behind. This one was called "Old Dutch," and he was all that the name would imply; still I was not "looking in his mouth", he was a horse. So I mounted and rode on over the top of the bluff where I found the greater part of Reno's command. We were soon joined by a few others who barely succeeded in making their escape. In times past I have wondered how a man felt, when he believed that almost inevitable, sudden death was upon him. I knew it now, for our escape was little less than miraculous when one considers the overwhelming number of Indians and the pitifully disorganized condition in which we made our death-encircled ride in the valley and up the bluffs, pursued by a howling mass of red warriors, naked to the waist, who, maddened and desperate by the terrified cries of their wives and children whose lives were put in jeopardy for the third time within a few weeks, rushed from their camps and, caring nothing for their own lives, were determined to save their families, or die. They seemed to us, in all their hideousness of paint and feathers, and wild fierce cries, like fiends incarnate, but were they? * * *

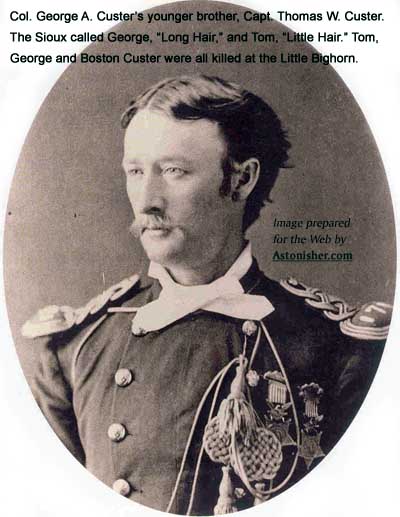

Major Reno was walking around in an excited manner. He had lost his hat during the "charge" and had bound a red handkerchief about his head, which gave him a rather peculiar and unmilitary appearance. Most of the men had thrown themselves on the ground to rest for they were well nigh exhausted. The officers were talking together, comparing notes and so forth. We had been there but a very short time when we were joined by Captain Benteen with the three Troops, H, D, and K, that had been sent off to the left some two hours before. They were now, in obedience to a written as well as verbal order, on their way to join Custer. This junction with all of Reno's command occurred at "2:30 p.m.," so Reno states. A very short time afterwards, Captain McDougall with B Troop, escorting the pack train, came along and joined us. Captain McDougall had also received an order from General Custer to make haste and join him with the pack train. The message to McDougall was delivered to him by Sergeant David C. Kanipe of Captain Tom Custer's Troop, C. It might be well to say here that Boston Custer, a younger brother of the General, was acting as a civilian forage master. He had been riding with the General that morning but had gone back to the pack train for a fresh horse, which having secured he started on ahead to rejoin the General's command. While on his way he met Trumpeter Martin[i] who was bringing a dispatch to Captain Benteen. Mr. Custer and the Trumpeter exchanged a few words and then continued their respective ways. Mr. Custer had time enough to rejoin the command before the battle began and his body was found within a few yards of those of his two brothers. For over two hours after the arrival of Captain Benteen's command we remained there on the bluff, unmolested in any manner. The First Sergeants of Reno's three Troops went around checking on the men present so as to know how many had been killed, wounded, or missing, and also taking an account of government property lost. We had heard firing off in the general direction Custer was supposed to have gone. "Why don't we move?", was a question asked by more than one. The three Troops that had been engaged in the valley were it is true somewhat demoralized, but that was no excuse for the whole command to remain inactive. A few of our men had been wounded, but none so seriously that they could not ride with the pack train. All of the officers must have known that Custer was engaged with the Indians and quite near by for he had not time to go a great way. The sudden withdrawal of that strong force of Indians who had driven us from the close vicinity of their camp, could indicate but one thing, and that was another attack on their camp, real or theatened, by a force from another direction.) In the latter part of the afternoon, not far from half-past four, a squad of twelve of our comrades were seen coming up the bluffs. Some of them had become dismounted in the woods or just outside when the com mand left and they remained hidden in the woods, strange as it may seem, until all the Indians appeared to have left that vicinity, when they came out and on foot started in the direction Reno had been seen to take. There was fourteen of the party altogether while in the woods but two of them refused to take the chances of escaping in the daylight and remained behind. They were afterwards discovered by the Indians and killed. The party that escaped consisted of George Herendeen, a scout, six soldiers of G Troop, three of M and two of A. While on their way they saw but five Indians whom they drove off with little trouble and no loss. After they had crossed the river, which was waist deep, one of the A Troop men found and recognized my horse grazing unconcernedly where I had left him. He brought the horse along, later on turning him over to me, who, he had supposed, was killed. Not an article of my equipment or belongings was missing although the horse had been for nearly three hours quite near, if not within the Indian line.

Soon after the party of twelve rejoined us and somewhere near five o'clock we had orders to "fall in", and mounting our horses we started in the direction Custer was believed to have gone. A very short ride along the side of the bluffs that shut off our view of the Indian village brought us to a ridge that afforded a partial view of what was afterwards found to be Custer's battlefield. Many Indians were seen in the distance, and others nearer by. Soon they began to come in our direction and our advance Troop under Captain Weir was attacked. The whole command was then ordered to retire and we returned to the place we had left a short time before. By this time the Indians had us completely surrounded and opened a furious fire. The pack train, wounded, and horses were placed in a depression between two ridges on top of which the men were posted, lying close to the ground. This was, according to my belief, about six o'clock, and that is the time set by Major Reno in his report. Captain Godfrey seems to think it was a little later but he must be mistaken for it certainly never took us two hours to travel about one mile and return to our starting place, especially when urged on by the advancing Sioux for whose power we were entertaining a greater respect than had formerly prevailed. Two good sized ridges sloping from the steep bluffs that overhung the river back toward the east formed the depression that afforded some shelter for our horses and wounded, although it was subjected to a constant long range fire from the east. Those whose lot it was to hold the horses lay just as close to the ground as they could, wishing most fervently for night to come for the day had been a very strenuous one and full to the utmost with danger that blanched the cheeks of officers and men, the veterans of many battles as well as the raw recruit that was but a few weeks in the Regiment. In later years when thinking of our position on the hill and the generally demoralized condition of the command, it has been to me a great wonder why that strong force of Indians that had swept over and annihilated Custer with his five Troops in such a brief time should have hesitated to pursue the tactics that won for them such a great victory an hour or two before. It was indeed most fortunate for us that they did not. The firing, however, was continuous on the part of the Indians until dusk and after that a few scattering shots, ceasing altogether about nine o'clock. Our casualties since taking position on the hill has been, Captain Godfrey says, "comparatively few." Personally, I knew of but three killed, and a few more, wounded. After it got dark some scouts were sent out to look for signs of Custer's command. They returned in a very short time and in considerable haste saying "the country was full of Indians." A Trumpeter was ordered to a little eminence to sound some calls which it was hoped might reach the ears of Custer's command and so direct them to our position. Facing the direction in which Custer had gone, three or four calls were blown with all the force the Trumpeter could give, the last, as I remember it, was "Taps", a call blown after "Tattoo", to put out the lights, and also always sounded over the grave of a soldier at the time of his burial. Was it not something more than mere chance which led the Trumpeter to send out on the still night air the notes of "Lights all out"? And as the echoes floated away in the darkness a deep feeling of sadness came over our hearts. Scattered around us near by were the fresh, and shallow graves of some who had fallen in our midst that afternoon and had just been covered by their comrades. No ceremony, a little trench right where they fell, a few inches of earth thrown over them, to be washed off by the first rain. Down in the valley, near the woods, and along the steep hillside lay others of our command unburied, men who fell in that headlong retreat. Still farther away but unknown to us then, were the mangled remains of over two hundred of our Regiment. It now seems most fitting that "Taps" should have been blown at that time, unthinkingly, but how appropriately, no answering call came to our anxious ears. The personal loss of intimate comrades, the great disaster to our Regiment, and our own narrow escape had a very sobering effect on all. And now comes a rather pecular incident, one that some may be tempted to question but which I aver to be strictly true. After the fire of the Indians had ceased altogether the men, glad to be relieved of the terrible strain of the last few hours, moved about quite freely and were naturally anxious to know what our next move would be. The First-Sergeant of company A having been wounded, his duties fell upon Sergeant Feihler, an elderly German of a rather placid nature. Our Company was considerably scattered and then I saw Sergeant Feihler near the low end of the herded horses and pack mules. I approached and said to him. "What are we going to do, stay here all night, or try to move away?" Major Reno was then standing quite near, and heard my question. He turned at once, with the remark, "I would like to know how in Hell we are going to move away?" I was quite surprised at his words and manner, but as I had certain ideas in my mind, I continued to Sergeant Feihler that "if we are going to stay here we ought to be making some kind of a barricade, for the Indians would be at us the first thing in the morning." Major Reno, who was still there, spoke up at once, saying, "Yes, Sergeant, that is a good idea. Set all the men you can to work, right away." Sergeant Feihler then began to order men to take boxes of hardtack, packsaddles, sides of bacon, dead mules and horses, in fact anything they could use, and make a barricade across the lower part of the depression. This was finally done, but not without a great deal of entreaty and urging by the Sergeant. For strange as it may seem, very many of the men showed but little interest in the work, and the officers, less. The only excuse I can offer for this seeming indifference was that they doubtless expected that General Custer would make his appearance during the night and that our labor would be wasted. That barricade proved of the greatest service to us the next day, saving the lives undoubtedly of many of the men who were not slow to seek its protection from the merciless fire opened on us the next morning. Commanding, as it did, the only feasible approach for a mounted charge against our lines, one of which the Indians started to make the next day, they met with such a warm reception at the very beginning that they gave up the idea at this point. Had it not been for this barricade it is my firm belief that they would have rode over us as they did over Custer's men. I do not know if Companies, M, K, B, and D, made any special attempts at this time, to fortify their position, but I saw no evidence of its being done, and as for "H," Troop, I know that they did not. Soon after our barricade was completed and not far from ten O'clock, p.m. I was detailed as picket guard. There were six Privates and one Corporal, the latter was Stanislaus Roy, all out of A Troop. We were advanced about three hundred yards down the slope in front of our breastworks, where two sentinels were quickly posted, one on the right and the other about one hundred yards to the left. A short distance in front of us were two hillocks some fifty yards apart, behind which of course we could not see. But they were used that afternoon and the next day as an advantageous place to pick off any of our men who recklessly exposed themselves. I was assigned as the second relief and so had a chance to sleep for two hours before my turn came. But before lying down I scrutinized as carefully as I could all the features of the landscape in front, especially the taller growth of sagebrush that might be mistaken in the dark for the stealthy approach of an Indian. Satisfied that I had the bearings pretty well in mind I lay down and in a moment was fast asleep, a deep, untroubled sleep, of which we were all greatly in need, having had but little the night before. It seemed like a very short two hours when I was awakened and went out to relieve the first sentinel who duly reported, "All's well". I took a position a little different from the one the other sentinel had, and sat down to watch, for walking would have made one rather conspicuous. The shouting and sound of the drums in the camps of the Indians could still be heard. It had been a day of intense excitement, of desperate struggle and final triumph, such a day they had never known before. The sudden appearance of the soldiers at the very edge of their camp, the rally of the warriors in defense of their homes, the defeat of the white men, of whom over two hundred lay cold in death on the plains and hills near by, a tribute to the prowess of the Indian. And what a booty had fallen into their hands, everything that a horseman needed. Horses, saddles, blankets, and the arms, over 200 carbines, as many revolvers, and ammunition to fit, money, and all kinds of clothing. There was indeed much cause for rejoicing and the "dancing of Scalps." But it was not all exultation. In many a lodge lay a cold red form brought from the near by field of battle, the lifeless form of a husband and father who had rode out so bravely but a few hours before to defend all that he had in life, his wife and children, and a little skin covered lodge. In other tepees, stretched out on a pile of robes lay some helpless from serious wounds, some even fast approaching the ghost land of their fathers, and bearing with the stolid indifference of the race their coming fate. For those who were dead there was loud lamentations, wailing deep and sincere, such was their custom. At one time during the night amidst the savage yells and discordant noise of the Indian drums we heard the sound of a bugle and it brought us all to our feet at once. "Custer was coming at last," was our first thought. We listened, again the notes of a bugle was borne to our eager ears, this time a little more distinct. But it was not an army call that I had ever heard or was familiar with at least. Though some declared it was. One thing was quite evident, it came from the camp of our foes below us. From where, as if to mock our budding hopes, came a renewed vigor to the beating of the drums and another and louder outburst of the wolf-like yells. The explanation was not hard for us then, for we remembered that one of the Trumpeters of G Troop had been killed in the bottom on our retreat and the Indians had undoubtedly possessed themselves of his bugle and were amusing their fellows and adding to the general din. That there was then probably eight or ten more bugles in the Indian camp, taken from Custer's five Troops, (each troop being allowed two), was something that could not have entered our minds. Many speculations have since been indulged in regarding this bugle episode. One theory being that some half-breed or Indian, who in the past had frequented some army post and become rather friendly with Trumpeter, had learned to blow a few calls, or something like them. Another theory was that one of Custer's Trumpeters had been taken prisoner and before being put to death was allowed, or else compelled to blow the bugle. To my mind, the most reasonable explanation is the one first given. My two hours duty passed quickly, the shouting and sound of the drums in the Indian camps were growing fainter and nothing more was heard except the long drawn-out and mournful howl of a prairie wolf over in the direction Custer had taken. When the third relief came on I reported, "All's well," and again sought the soldier's couch, the rough hard ground, and as before was soon fast asleep. My next awakening was in the early dawn as I had expected it would be. For about three o'clock just as it was growing light there came two rifle shots from a low ridge in our front. This may have been the Indians' signal to open fire, for in less time than it takes to write about it a perfect shower of bullets followed from all along their line. [Note: See Indian Battlefield Tactics for more info.] It was hardly necessary for the Corporal to order us back to our lines. We went and went quickly, and on our arrival threw ourselves down behind the breastworks, the construction of which was now showing its wisdom. Besides the greater part of A Troop engaged in holding this line of defense the force consisted of a number of stragglers from other Troops and several citizen packers. At one time during the day, I observed an officer whose company was in another part of the field, and one more perilous than ours, safely sheltering himself behind the thickest part of our breastworks. * * * From the time the Indians began firing early in the morning until late in the forenoon, there was no time that it was prudent for a man to raise his head above the barricade. Not that the Indians kept up a continuous fire, their ammunition was too costly for that. But let a man stand up, or expose even a small part of his body and the act was followed by a shower of bullets which, however, did not always hit their mark as the following incident will show. Captain Benteen, who has been criticized for not being more prompt in obeying Custer's orders, was nevertheless one of the bravest acting men of our entire command. His Troop was holding a position on a ridge to the right of our breastworks, and a few hundred yards south, as near as I can recall the points of compass. They had neglected to dig any pits or make any other provision for shelter from the fire, which an old soldier like Captain Benteen must have known would be directed against his line the next morning. Therefore, owing to their exposed position, they suffered quite severely in [number] of wounded, no less than ten, and one account says eighteen men were wounded, and three killed outright. As a result, Captain Benteen came over to where our line was and asked Captain Moylan for some of the material our barricade was made of, the barricade being a little longer than was necessary for the number of men behind it. All this time Captain Benteen was in full view of the Indians, making no effort whatever to seek any shelter. You could see the bullets throwing up dust as they struck all around him while he, as calmly as if on parade, came down to our lines and, after his errand, returned in the same manner carrying in his hand a carbine, with which I observed him measuring the distance from his foot to a point where a bullet had just entered the ground in his front less than two feet away. This incident was impressed on my mind by the fact that I was in the same zone of fire, being but a short distance from him at the time. I was one of the party detailed to carry up some material for Benteen's breastworks, and with a box of hardtack on my shoulder was hurrying up the ridge. It was a trying time and when a bullet crashed into the box on my shoulder, nearly knocking it off, I had some doubts about ever finishing the trip, short as it was. But I did and unharmed. When we started back to our own Company we took a circle around more to our rear and in a little less exposed position. I had but just reached my place behind the works when the man next to me on the left, and whom I could almost touch without moving, raised his head just enough to take a shot when a bullet struck him right between the eyes. It was instant and painless death for he did not make a move or a sound. This man was one of the citizen packers named Frank Mann. He had been quite noticeable for his continuous firing without any apparent cause or result, and had been warned not to expose himself so much. But the warning was of no effect and he was finally located by an Indian sharpshooter and put out of business. A few moments afterwards another comrade and myself moved the body back a few feet, for it was too suggestive lying there between us, and as I had lost my own revolver I took the one carried by the packer, it being of Government issue and of no more use to him while it might be of great service to me at any moment. Life seemed very attractive throughout that eventful day for such close acquaintance with death is not a pleasing sensation, and I think that most of the soldiers felt that unless a special providence interfered we were certainly doomed. During the forenoon Captain Benteen went over to the north side where Major Reno was and asked him for reinforcements. He believed that the Indians would soon charge his position, and as he has but one troop [H] to hold the south line, the chances were that if the Indians did make a rush they would run right over the few men left in his Company and have all the rest of us between two fires. After some urging Reno finally ordered Captain French to take his troop [M] over to the south side. Soon after the arrival of M Troop, Benteen ordered a charge and succeeded in driving the Indians from his front nearly to the river. A number of the soldiers were wounded but only one seriously. And that was Private Tanner of M Troop who fell a short way down the hill. After the charge, a party of his comrades rushed down the slope, rolled him on a blanket and amidst a severe fire bore him back to the lines where he died soon afterwards [Note: Here is Peter Thompson's description of Benteen's charge, which he took part in. Here is John Ryan's account of Tanner's death.] The firing would almost cease at times and then begin again more furious than ever, but it finally slackened toward noon and a call was made for volunteers to go to the river after water which we had been without for many hours. There is no questioning the fact that the thirst of many was intense, but I do doubt that there was any real suffering unless it was in the case of some of the wounded. Still it was not pleasant to go twenty-four hours without a drink of water, especially on a hot day in June while within a few hundred yards flowed a river of clear cool water, and off to the southwest could be seen the snow topped range of the Bighorn mountains, seemingly but a short distance. Various expedients had been tried to alleviate our thirst; chewing lead from a bullet and the inner part of the thick leaves of the prickly pear, holding pebbles in the mouth, etc. All were useless, if not an aggravation. The call for volunteers met with a quick and full response; and covered by some of the best marksmen in the front of Benteen's line, a party with camp kettles and canteens made their way down a ravine that approached within a few yards of the river. Then, making a rush, they reached the river, filled the kettles and hastened back to the ravine where the canteens were filled. Some Indians stationed near by on the opposite side opened fire as soon as a man appeared, making the undertaking a very hazardous one and several of the men were wounded, one of them so badly that one of his legs had to be amputated. This man was Michael Madden, a Saddler of K Troop. This undertaking seemed to me at the time a foolish one and uncalled for under the circumstances. The almost dead certainty of putting five or six men hors de combat at a time when every man was needed who could fire a gun, was not, in my opinion, justified in any way by the exigencies of the case. In the course of an hour or two afterwards most of the Indians appeared to have left. But I think this was their last card and they were in hopes of throwing us off our guard, for about two o'clock they reopened fire and drove us all to our shelter. This last attack was not of long duration, for after a time the firing ceased altogether. They later set fire to the grass in the bottom and shortly afterwards a great mass of Indians were seen in motion going up the valley in the direction of the Bighorn Mountains. It was a most joyful sight to us for we had spent the better part of two days in a decidedly nerve-strained condition and I doubt if a dirtier, more haggard looking lot of men ever wore the Army blue than that little remnant of the once proud Seventh. It was fast approaching twilight when Major Reno decided to change his position to one nearer the river. The men were set to work digging pits with the expectation of still more fighting; and, besides, the stench from the dead men and horses was becoming very offensive. It did not now take so much urging, they had learned a lesson and in a few hours we had some pretty fair pits constructed, which, I have been informed, are still to be seen.' The one upon which I worked was circular in form and room enough in it for six or eight men. Our tools were tin cups and plates, knives, sharpened paddles made out of pieces of hardtack boxes, and a few shovels.

Tuesday morning June 27th, found us up bright and early eating in peace our breakfast of bacon, hardtack and coffee. We watered our horses who acted as if they would never get enough, washed our faces and hands and straightened ourselves up generally. Not an Indian was in sight and no shots were fired to keep us ducking. Major Reno seemed determined to stay where he was and kept the men in readiness to occupy the pits should the Indians return. About the middle of the forenoon a cloud of dust appeared down the river and we half expected a renewal of the fight. The horses were secured, water brought up and we awaited the coming of whatever it might be. Soon a scout appeared with a note from General Terry to General Custer. The scout was soon followed by Lieutenant Bradley of the Montana Column and his detachment of scouts from whose lips came the first news of the terrible disaster that had befallen Custer's command, which we were even then hoping might be the cause of the dust cloud coming up the valley. This however, proved to be the Montana Column, accompanied by General Terry, who with General Gibbon and several other officers were shortly in our midst. Captain Godfrey says, "their coming was greeted with prolonged cheers, the grave countenance of the General awed the men to silence, the officers assembled to meet their guests, there was scarcely a dry eye, hardly a word was spoken, but quivering lips and hearty grasping of hand gave token of thankfulness for the relief, and grief for the misfortune." General Gibbon's command soon arrived at a point in the valley nearly opposite our position and went into camp. One of his officers, Lieutenant Coolidge of the Seventh Infantry, who had some medical experience, was sent up to assist Dr. Porter in the care of our wounded of whom there were some fifty-two. The wounded were moved as soon as possible to the camp of the Montana Column. This work was rather difficult in the case of those who were seriously injured and helpless, for they had to be carried in blankets down a steep bluff and then through a river that was nearly waist deep. The men exercised all the care and consideration that they could, but it must have been a great relief to the wounded when safely deposited in their new "field hospital," a grassy bed, protected from the sun by a piece of shelter-tent. The rest of the day was spent in collecting our effects, destroying all surplus property that could not be taken along and which might be of some use'to the Indians, gathering up the bacon and hardtack, and other useful material from the barricade, besides dispatching a number of badly wounded horses and mules. During the day I went over in front of Benteen's position, where, down the slope a few yards, lay the body of that recklessly brave warrior who had tried to count a coup' on one of Benteen's men. I had seen quite a number of the "quick" ones, and at last was to gaze on a "dead" one. There were but two left on our field, one near the ford where we ascended the bluff, and this one. In a little depression there lay outstretched a stalwart Sioux warrior, stark naked with the exception of a breech clout and moccasins. He lay with his head up the hill, his right arm extended in the direction the fatal shot had come, a look of grim defiance on his face, which was not disfigured with the streaks of yellow, green, and crimson, so common to many. Perhaps in his hurry to get into the fight he could not stop to don his war paint. He had been scalped by some soldier, the greatest misfortune that could happen, for thereby his soul was annihilated; such was the belief of his people, and for him now there was no Happy Hunting Ground. Never had I seen a more perfect specimen of physical manhood, he must have been about thirty years old, nearly if not quite six feet in height and of splendid proportions. He looked like a bronze statue that had been thrown to the ground. It was such a form that MacMonnies might have had for a model when he sculptured "The Last Arrow". I could not help a feeling of sorrow as I stood gazing upon him. He was within a few hundred rods of his home and family which we had attempted to destroy and he had died to defend. The home of his slayer was perhaps a thousand miles away. In a few days the wolves and buzzards would have his remains torn asunder and scattered, for the soldiers had no disposition to bury a dead Indian, and his family and tribe were even then in full retreat. I have since learned that his name was High Elk. His medicine bag, which was all the property he had left on him I brought away as a souvenir of a very brave man in a memorable battle. It was carried on a belt and was made from the leather of a bootleg, fashioned in shape and size like a pistol cartridge box, and sewed together with fine wire, the flap studded with brass tacks. Among its contents were three little parcels of different colored dry paint, each done up in a piece of soft buckskin, a piece of dry flagroot, part of a coarse comb, a few matches and some thread and needles. I have often wondered since that day, if, in a few years after his bleached and scattered bones were not found by the Superintendent of the Custer National Cemetery who might quite naturally think that they were the remains of some of Reno's command that had been overlooked by the first burial party. And so he might have had them gathered up and buried among those whom he had fought against... * * * Soon after five o'clock on the morning of the 28th, the remnant of our Regiment swung into the saddle again and bade farewell to that memorable spot and the scattered graves of our late comrades. It had been our enforced abiding place for two and one half days, and for a great part of the time, it looked as if we had reached the end of our earthly journey. We left it, carrying with us a memory graven deep in our minds of those thrilling scenes when for hours we looked death in the face. Our errand now was to seek our comrades who had died with Custer, and pay our last respects by a scant and hasty burial. After riding a short distance north, perhaps a little over one and a half miles, we came to an elevation from which a part of the battlefield could be seen. A bleak, dreary place, where, aside from a little coarse grass, nothing grew but an abundance of wild sage and a variety of cactus called prickly pear. Over it there seemed to hang an atmosphere of sadness and desolation, and little wonder that there was, for from every body on that bloody field but a few hours before had gone forth in vain most anxious looks and prayers for our appearance, which would have meant so much, the salvation of many lives. The actual field of battle was less than one mile in length and perhaps one half mile in width, the main part being on a ridge that rap nearly parallel with the river and about a mile from it. Most of the bodies were on the slope of the ridge but there were quite a number scattered between the river and the ridge, and how white they looked at a distance, like little mounds of snow. The command now separated, each troop or detachment going over a certain section of the field. Major Reno, who was in command, taking the precaution to send Lieutenant Varnum with his remaining scouts well out on the flanks to guard against any surprise. We had but little in the way of grave digging implements, one spade to a company and that was brought along by the company cook for the purpose of cutting a trench for his fire, so the decent and proper burial of over two hundred bodies was not possible in the limited time at our disposal. The most that could be done was to cover the remains with some branches of sagebrush and scatter a little earth on top, enough to cover their nakedness, a covering that would remain but a few hours at the most when the wind and rain would undo our work, and the wolves whose mournful and ominous howls we had already heard would scatter their bones over the surrounding ground. The first body found was recognized as that of Sergeant Butler of L Troop, [Lieutenant Calhoun's Company] a soldier of proved courage and a veteran of many Indian battles. He was lying near the foot of a hill and about one mile from where Custer fell and, according to the most reliable map but a little more than a mile in an air line, from Major Reno's position. His body was perfectly nude, and somewhat mutilated but not so badly as some of the others. From some statements made to the writer by an Indian who took part in the battle, theknown character of the Sergeant, and the circumstances under which his body was found, it seems altogether probable that he was selected by General Custer soon after the fight began, to make an effort to reach Captain Benteen and hasten his approach, for the situation was becoming serious. He took the message and started back at a rapid gait and had made quite a little distance before any effort was made by the surprised Indians to stop him. And he might have succeeded in getting away but just as he started to ascend a ridge there appeared on the top a party of Indians coming over from Reno's position. There was no chance for the Sergeant, the party that had started in his pursuit had got his range while the bullets of those in his front were singing about his ears. Escape was impossible. He sprang from his horse, unslung his carbine and the mute testimony of six or eight cartridge shells by the side of his body was sufficient evidence that he had made a gallant fight. ". . . He knew no creed but this, in duty not to falter, with strength that nought could alter to be faithful unto death. " None of the bodies that I saw had any clothing on whatever and nearly all were mutilated in a terrible, and in some cases most disgusting manner. This was the case all over the field, with very few exceptions, General Custer and Captain Keogh being the only one that I heard of, these two I did not see. That great Russian artist, Tatkeleff, in all his pictures depicting the horrors of war has nothing that equalled the horrible sights presented to our view that morning. Heads crushed to an unrecognizable mass by stone war clubs, arms and legs slit with keen knives, parts of the bodies dismembered, and trunks cut open, and many with arrows left sticking in them. Nothing whatever of the belonging of man or horse was left on the field that I could see, the squaws had swept it clean. The sagebrush, broken and trampled by the horses and ponies of the contending forces, gave forth a strong odor which, mingled with that of the swollen and fast decomposing remains of horses and men, was sickening in the extreme, and yet so hardened or indifferent were some that I saw men sitting down close by a mangled body and calmly munching their bit of hardtack and bacon. Some of the officers went galloping over the field looking at different bodies in the hope of recognizing the three missing Lieutenants; Harrington, Porter, and young "Jimmy" Sturgis. The latter was our Colonel's son, and just out from West Point. But their search was fruitless although they went so far as to feel the palms of one body near me looking for a clue in the way of a soft, uncalloused hand. This body was nude like all the rest and in it were several arrows, two of which I pulled out and brought away. Some of the clothing of young Sturgis, bearing his name was found in the deserted Indian camp. But his body was never found, to be recognized, all statements to the contrary notwithstanding. Lieutenant Nowlan of I Troop of the Seventh, [Captain Keogh's Company] who was at that time serving on the staff of General Terry, is said to have marked the resting place of many of the officers by driving into the ground a stake, into the head of which had been forced an empty cartridge shell containing the name of the party it was designed to mark. I did not see any such work done nor is the statement verified by First-Sergeant John Ryan, of M Troop, who had charge of the detail that buried General Custer and his brother, Captain Thomas W Custer. In the burial of these two he was assisted by Privates Harrison Davis, Frank Neeley, and James Seavers all of M Troop. Sergeant Ryan in whose company I served for four years, writes me to the following effect: "The body of General Custer although perfectly nude was not mutilated 4 He had been shot in two places, one bullet had entered his body on the right side and passed nearly but not quite through, the second bullet, and undoubtedly the fatal one, passed through his head entering close to the right ear and coming out near the left ear. Under his body was found four or five brass cartridge shells which, with a lock of his hair, was afterwards sent to his widow.

But one other body was placed in a grave by Sergeant Ryan's party, and that was Lieutenant WW Cooke. He was identified by his long black side whiskers, one of which had been taken off for a scalp, for if my recollection is correct the Lieutenant was a little bald. He was the Regimental Adjutant and a long time friend of General Custer. It has always seemed rather strange to me that the remains of General Custer were not brought along with the wounded and shipped with them on the steamer Far West, to Fort Lincoln. There was plenty of salt and strong canvas to wrap the body in, and the steamer was but a few miles away. The Indians carried away many of their dead, why could not the white man do as much for one as distinguished as General Custer? Rightfully or otherwise, there was at the time among the enlisted men at least, a deep feeling of resentment against the General. How far this feeling prevailed among the officers, high and low, is not for me to say. Among the men it was felt then that their comrades had been needlessly sacrificed and their own lives put in jeopardy to further ambition. Later on, when more was known in regard to the numher of Indians engaged and certain circumstances connected with the affair, the feeling among the men was greatly changed. Having completed our sad duty the command reassembled and started for the ford where the Indians had crossed, intending to go up through the abandoned camping places of the Indians to the camp of General Terry's command which was partly on the ground where Major Reno made his attack. It was not until then that the magnitude of the forces we had engaged dawned upon us. Stretched along the river for miles following its many bends, close up to the bluffs, and then into the prairie was a vast number of lodge sites. Terry's engineer officer counted some eighteen-hundred, so it was reported at the time, and I have never felt like questioning the number. On every hand as we rode along was the evidence of a hasty flight, an immense number of lodge poles, robes, dressed skins, pots, kettles, cups, pans, axes and many other articles among which I saw several decorated box-like receptacles made of rawhide, a kind of traveling trunk I suppose. Also sleeping mats, made of small willow sticks that rolled up like a porch shade. Several war clubs were picked up with the sickening evidence on them of a recent use. We had gone but a short distance when over toward the river among the bushes was seen a cavalry horse. Upon investigation it proved to be the horse of Captain Keogh, a claybank in sorrel color, and named Comanche. He was stripped of all equipment and was a pitiful sight, there being no less than seven wounds on his body, from bullet and arrow, from which the blood had hardly dried. On his mane, where there was no wound was some dried blood which was probably the blood of Captain Keogh. The horse certainly bore a charmed life for he had been wounded once before in an Indian battle while ridden by Captain Keogh. Major Reno gave orders that the horse be secured and taken along with the command, of him more will have to be said later on. * * * Before leaving this scene of the greatest Indian victory known in our history, I must mention one more incident in connection therewith. Late in the afternoon of the 25th, and again on the 26th while we were besieged on the bluffs, two or three smoke signals were plainly seen for a long time on the hills west of the Indian village. They did not attract much attention from our command as no one seemed to understand their meaning. To us they were simply "Indian signals" of some kind. They were, in appearance, very high and straight pillars of smoke, varying at times in depth or intensity of color, sometimes being quite light and then again very dark. It was not until long afterwards that the true import of these signals became known to us. Little we thought at the time that news of our battle was being sent to all points of the compass, wherever there was a Sioux camp, or warrior. Incredible though it may seem, it is doubtless a fact that the defeat of a large body of soldiers on the Greasy-Grass, [Little Bighorn] was known to the Agency Indians on the Missouri river and elsewhere many days before the whites had any inkling of Custer's defeat. [Note: here is T.R. Porter's article on this subject from the Custer Battle Book.] It was more than nine full days from the afternoon of June 25th before the first news was heard by the outside world through the arrival at Bismarck on the morning of July 5th of the steamer Far West, bringing back the wounded and the news of Custer's last battle. That something serious had happened to the military was suspected by many at Fort Lincoln for several days before the arrival of the Far West. The Indian scouts attached to the Post betrayed by their actions that they had heard some important news. The same thing was noticed to even a greater degree at Standing Rock Agency, some sixty miles below Fort Lincoln. Lieutenant J.B. Rodman, of the 20th Infantry, who as Regimental Adjutant was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, near St. Paul, and some 435 miles from Bismarck, was informed on the third day of July [just about the hour the Far West started from the mouth of the Bighorn with our wounded] by an old Sioux Indian whom the Lieutenant had often befriended -- "that a great battle had taken place between the Indians and the soldiers on the 'Greasy Grass', (Little Bighorn) that the battle lasted for two days, and many soldiers and chiefs were killed, and more soldiers were coming. That the Indians where he lived (Mendota) all knew about it and were dancing and singing." The story was not credited in the least by the Lieutenant who flatly called his informer a dreamer, or a liar. But on Wednesday morning, forty eight hours afterwards, the Steamer Far West arrived at Bismarck, Dakota, and the first news of the disaster was flashed over the wires to the people of the States. A few hours later when the news reached Fort Snelling, the old Indian was sent for and told to repeat his story, and was asked this question, "How on earth could all this have reached you Indians at Mendota, forty eight hours before the telegraph could tell us?" The old blind Indian replied, "Indians use Indian runners, mirror flash, fire arrows, fire and smoke, Indians tell that story faster than the fastest pony." In September 1880, an outbreak occurred at Fort Reno [Indian Territory] sixty miles from the location where Colonel Dodge was stationed, yet his Indian scouts knew of it and so informed him before he heard of it by the telegraph line between the two places. That this Indian method of sending news may be more readily understood, I will quote a few lines from Smoke Signals in the Ethnology Report of 1879-80, page 537. "The highest elevations of land are selected as stations from which signals with smoke are made-they can be seen at a distance of from twenty to fifty miles, by varying the number of columns of smoke different meanings are conveyed. Building a small fire which is not allowed to blaze, they put an armful of partially green grass or weeds over the fire, as if to smother it, a dense white smoke is created, which ordinarily will ascend in a continuous vertical column for hundreds of feet. By covering and uncovering it at proper intervals, a succession of elongated egg shaped puffs of smoke are kept ascending toward the sky in the most regular manner. These bead-like columns of smoke are visible on the level plain fifty miles distant"... With Custer On The Little Bighorn: A Newly Discovered First-person Account, by William O. Taylor, forward by Greg Martin, Viking, New York, 1996, p 30-42, 47-55, 57-63, 73-79, 113-115

|

||||||||||

THE MARCH during the day [Note: June 24, 1876] had been a rather tiresome one for we had halted many times in order to give the scouts an opportunity to thoroughly examine the valley ahead of us. After our horses had been fed and rubbed down, and our simple meal of coffee and hardtack disposed of the men, spreading their piece of shelter tent and blanket on the ground, lay down for a much needed rest.

THE MARCH during the day [Note: June 24, 1876] had been a rather tiresome one for we had halted many times in order to give the scouts an opportunity to thoroughly examine the valley ahead of us. After our horses had been fed and rubbed down, and our simple meal of coffee and hardtack disposed of the men, spreading their piece of shelter tent and blanket on the ground, lay down for a much needed rest. Soon afterwards the Regiment was divided into Battalions, the advance Battalion under

Soon afterwards the Regiment was divided into Battalions, the advance Battalion under  Some of the men began to cheer in reply to the Indians war whoops when Major Reno shouted out, "Stop that noise," and once more there came the command, "Charge!" "Charrrge!" was the way it sounded to me, and it came in such a tone that I turned my head and glanced backward.

Some of the men began to cheer in reply to the Indians war whoops when Major Reno shouted out, "Stop that noise," and once more there came the command, "Charge!" "Charrrge!" was the way it sounded to me, and it came in such a tone that I turned my head and glanced backward. In the "Count Off" that morning I was number four, hence when the Troops were dismounted, to fight on foot, every fourth man had three led horses to care for.

In the "Count Off" that morning I was number four, hence when the Troops were dismounted, to fight on foot, every fourth man had three led horses to care for.

The fire and pursuit by the Indians seemed to cease as soon as we reached the top of the bluffs, this was much to be thankful for although we little dreamed of the cause.

The fire and pursuit by the Indians seemed to cease as soon as we reached the top of the bluffs, this was much to be thankful for although we little dreamed of the cause. I may state right here that another party of our men had also remained in the woods. Unseen and unknown by the party just mentioned, this second party consisted of

I may state right here that another party of our men had also remained in the woods. Unseen and unknown by the party just mentioned, this second party consisted of  With relaxed nerves and tired bodies we stretched ourselves out on the bare ground for the first good, whole night's rest since the 23rd. Sometime during the night four of our missing comrades showed up in two separate parties. Lieutenant DeRudio and Private Tom O'Neil of G Troop came in about twelve o'clock, while Frank Girard, the interpreter, and a half-breed scout named [William "Billy"] Jackson came along at some other hour. They had been left in the bottom like many others when Reno made his retreat and were quite fortunate in finding us, and very happy also. They had been concealed in the woods along the river since two o'clock p.m. of the 25th in close proximity to the Indians who were on their way to and from our beleaguered lines.

With relaxed nerves and tired bodies we stretched ourselves out on the bare ground for the first good, whole night's rest since the 23rd. Sometime during the night four of our missing comrades showed up in two separate parties. Lieutenant DeRudio and Private Tom O'Neil of G Troop came in about twelve o'clock, while Frank Girard, the interpreter, and a half-breed scout named [William "Billy"] Jackson came along at some other hour. They had been left in the bottom like many others when Reno made his retreat and were quite fortunate in finding us, and very happy also. They had been concealed in the woods along the river since two o'clock p.m. of the 25th in close proximity to the Indians who were on their way to and from our beleaguered lines. It was a very difficult matter to identify the body of Captain Tom Custer. He lay some ten or fifteen feet from the General and had been most shockingly mutilated. He had been split down through the center of his body and through the muscles of his arms and thighs, his throat was cut and his head smashed flat. When found he lay on his face. It was not until Sergeant Ryan recalled that when Captain Custer was First Lieutenant of M Troop, in 1873, he had noticed on one arm of the Lieutenant in India ink the letters T.W. C. A careful search was made and although the arm was cut and somewhat blackened, the letters were found, and the body identified. A grave about eighteen inches deep and wide enough for two was dug, and wrapped in some pieces of shelter tents and blankets. The bodies of General Custer and his brother Captain T W Custer were laid therein, a little earth placed on them, a basketlike affair torn from an Indian travois was laid upside down over the grave and some stones laid on the edges in the hopes of keeping the wolves from digging it up, and the burial of General Custer was done."

It was a very difficult matter to identify the body of Captain Tom Custer. He lay some ten or fifteen feet from the General and had been most shockingly mutilated. He had been split down through the center of his body and through the muscles of his arms and thighs, his throat was cut and his head smashed flat. When found he lay on his face. It was not until Sergeant Ryan recalled that when Captain Custer was First Lieutenant of M Troop, in 1873, he had noticed on one arm of the Lieutenant in India ink the letters T.W. C. A careful search was made and although the arm was cut and somewhat blackened, the letters were found, and the body identified. A grave about eighteen inches deep and wide enough for two was dug, and wrapped in some pieces of shelter tents and blankets. The bodies of General Custer and his brother Captain T W Custer were laid therein, a little earth placed on them, a basketlike affair torn from an Indian travois was laid upside down over the grave and some stones laid on the edges in the hopes of keeping the wolves from digging it up, and the burial of General Custer was done."