|

||||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... George Bird Grinnell's

CROOK'S FIGHT ON THE ROSEBUD, 1876 IN 1874, GENERAL CUSTER led an expedition to the Black Hills of Dakota, and prospectors who accompanied him discovered gold. The announcement of this find caused much excitement, and parties of prospectors at once began to lay plans for invading the hills. That region was then one of the few untouched hunting grounds left to the northern Indians, and certain species of game, as deer and bears, were very abundant there. During the year 1875, the Sioux Indians made active objection to the incursions of miners into the Black Hills. Many parties were attacked, and not a few people were killed. The government endeavored to purchase the Black Hills from the Indians, and a number of groups of Sioux agreed to sell, but others refused. In the spring of 1876, the War Department determined to punish and reduce the hostile Indians who were living in Montana, Wyoming, and North Dakota, and Generals Terry and Crook set on foot operations looking to this end. General Terry was to ascend the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers and from some favorable point there to work south, while General Crook was to operate from the south north and to cover the headwaters of the Powder, Tongue, Rosebud, and Big Horn rivers. On May 29, with a strong column of about fifteen troops of cavalry and five companies of infantry, General Crook left Fort Fetterman for Goose Creek. On June 9, on Tongue River, the command was attacked by Indians, and two men were wounded. The Indians, however, were easily driven off. Captain Bourke credits this attack to Crazy Horse, but as a matter of fact, these Indians were Northern Cheyennes from the camp on the Rosebud, at the mouth of the Muddy. Led by Little Hawk, they had rushed over to Tongue River in the hope of driving off a lot of horses. The Cheyennes say that the soldiers met them with a long rain of bullets, and they gave up the attempt and returned to their camp. On June 17, at the bend of the Rosebud, an important engagement took place. It is commonly spoken of as Crook's fight on the Rosebud and was in fact a victory for the Indians. The Record of Engagements declares that Crook had less than one thousand men, and that the Indians were driven several miles in confusion, while a great many were killed and wounded in the retreat. The troops lost nine men killed and eighteen wounded, one of whom was Captain Guy V. Henry, who happily recovered. The official documents state that the scene of the attack was at the mouth of a deep and rocky canyon with steep timbered sides, and it is intimated that this was the reason for General Crook's retiring to his main supply camp to await reinforcements and supplies. I am familiar with the ground and have been over it more than once. The lay of the land scarcely bears out the description the reports give. The fight took place in a wide, more or less level valley, with high bluffs on either side. It is true that two or three miles below the battlefield the river bends sharply to the left and the valley becomes narrower, with high more or less wooded bluffs on either side, but, though varying somewhat, the width of the valley is for the most part a mile or two, and is nowhere, I think, less than half a mile. There is no "dangerous defile" such as is told of. There was no effort by the Indians to lead the troops into a trap. The ground was not suitable. It has long been well understood by those familiar with this fight that General Crook was thoroughly well beaten by the Indians, and that he got away as soon as he could. Considering the number of men engaged, the losses were not heavy on either side. At the same time it was a hard battle. The story as told from the military point of view can be found in the Record of Engagements, in Captain Bourke's On the Border with Crook, and in Finerty's Warpath and Bivouac. In the account given by the Cheyennes who fought in this engagement will be recognized a number of incidents spoken of by Bourke. The Indian narrative comes from several men, well known to me for many years, who took part in it. The man who discovered the presence of the soldiers on the Rosebud was Little Hawk, the son of old Gentle Horse, who sixty or seventy years ago was one of the most famous of Cheyenne warriors. From the fact of this discovery it has been the duty of Little Hawk of late years, whenever the ceremony of the medicine lodge has been held among the Northern Cheyennes, to go out and choose the center pole for the medicine lodge. The Cheyennes were camped on the stream now known as Reno Creek. In the early summer Little Hawk, then a leading warrior, called four young men, Yellow Eagle, Crooked Nose, Little Shield, and White Bird, and said to them: "Let us go out and see if we cannot get some horses from the white people." They started that night, passing through the Wolf Mountains, and then stopping to wait for daylight. When morning came they went on through the hills, and about midday reached the big bend'of the Rosebud. As they went down into the Rosebud they saw a great herd of buffalo bulls, and Little Hawk said: "Now let us kill a bull and stop here and roast some meat." He killed one close to the stream and near by found a nice spring of water. One of them started a fire, and they began to skin the buffalo. Before the meat was cooked, a large herd of cows came in sight. The young men said to Crooked Nose: "You stay here and roast this meat, while we go up to those cows and see if we cannot find a fatter animal." They went toward the cows, and after they had gone part way, one of them happened to look back to where Crooked Nose was cooking and saw that he was making motions to them from side to side, calling to them to come back. They thought no more about killing a fat cow, but turned their horses and rode down to him. When they reached him, Crooked Nose said to them: "On that hill, by those red buttes, I saw two men looking over, and after looking a little while, they rode up in plain sight, each one leading a horse. The rode out of sight coming toward us. I think they are coming in our direction-right toward us." Little Hawk said: "Saddle up quick. I think those men coming are Sioux; now we will have some fun with them"; for he thought that they could creep around and pretend to attack them, and so frighten them. The Sioux were friends and allies. They saddled their horses and rode up a little gulch, and when they had gone a short distance, Little Hawk got off his horse and crept up to the top of the hill and looked over. As he raised his head, it seemed to him as if the whole earth were black with soldiers. He said to his friends: "They are soldiers"; but he said it in a very low voice, for the soldiers were so near to them that he was afraid they would hear him speak. He crept down the hill and got on his horse, and Little Shield said: "The best thing we can do is to go back to where we were roasting meat. There is timber on the creek, and we can make a stand there." Little Shield spoke in a low tone of voice, and Little Hawk did not hear him say this, but started down the gulch as hard as he could go, and the others after him. As he was riding at headlong speed, he lost his field glasses, but he did not stop. He went down to the Rosebud and rode into the brush, and through it, up the stream. He left a good many locks of his hair in the bushes. While they were going up the creek, they did not simply gallop; they just raced their horses as fast as they could go. Keeping on up the Rosebud in the timber and so out of sight of the troops, who had not yet reached the river, they came to a high butte about three miles above the soldiers. They had not yet been discovered. Here they stopped and looked back. They could see the soldiers still coming down the valley. If the Cheyennes had not killed the buffalo, they would have kept on their way and would have ridden right into the soldiers. The buffalo bull saved their lives. When they left this round butte, they rode on over the mountains toward the Little Big Horn River. After, they had crossed the mountains, they passed along the foothills of the Wolf Mountains, and just as day began to break came to the camp, which had moved only a little way down Reno Creek. When they were near the camp, they began to howl like wolves, to notify the people that something had been seen. They reached camp just at good daylight. The people in the camp on Reno Creek had suspected that there were soldiers in the country, and some of the young men of the village had spent the night riding around the camp as if they were guards. Nothing had happened during the night, but now early in the morning they heard someone howling like a wolf, and when they heard this, they knew that some discovery had been made. Young Two Moon-son of Beaver Claws and nephew of the chief Two Moonrode toward the howling as soon as he heard the sound and met the scouts coming in. Little Hawk said to the people: "Near the head of the Rosebud, where it bends to turn down into the hills, we saw soldiers as we were roasting meat. I think there are many Indians with them, too. They may come right down the Rosebud. Get ready all the young men, and let us set out." All the men began to catch their horses and painted themselves, put on their war bonnets, and then paraded about the camp, and then set out to meet the soldiers, going straight through the hills. Little Hawk led a party of men who went straight across through the Wolf Mountains? With young Two Moon's party were about two hundred men-Sioux and Cheyennes-and one woman, the sister of Chief Comes in Sight. When this party reached the mouth of Trail Creek, on the Rosebud, they were stopped by the Cheyenne soldiers, who had formed a line and would not let them go on up the stream, because Little Hawk had expressed the opinion that the soldiers were coming down the Rosebud River. On the west side of the Rosebud, near where William Rowland's place now is, is a high hill which commands a wide view, and to the top of this high hill four Indians, who were serving as scouts for the troops, had gone to look over the country to see if any Indians could be seen. From young Two Moon's party four men, two Sioux and two Cheyennes, were sent forward to this same hill to see if they could discover the troops, and were told if they found them to come back at once. Some time after these four scouts had started, the main party moved on after them. The scouts sent out by the troops reached the top of this hill before the scouts sent by the Indians had passed out of the bottom. They saw the approaching Sioux and Cheyenne scouts, and began to fire at them. When the Sioux and Cheyennes who were farther down the Rosebud heard the shooting, they rushed up the valley, and the scouts from the troops retreated over the high land, while the Indian scouts, having signaled their people that they had seen something, followed them toward the soldiers. The soldiers, hearing the firing, formed in line and prepared to fight. The rifles began to sound more to the right, and the Indians, leaving the bottom, cut across the hills toward the river above. When they reached the top of the hill looking down into the valley of the Rosebud, they could see the soldiers following some Indians back into the hills. The soldiers were pretty strong and were fighting hard. The horses of the Indians were being wounded and falling as they climbed the hill. When the Sioux and Cheyennes saw this, they did not stop long on the high divide, but charged down on the soldiers, who stopped pursuing the other group of Indians and fell back. Little Hawk, with his party, who had been running away, then turned and charged back so that now there was a large body of Indians charging down on the soldiers. The sister of Chief Comes in Sight charged with the men. At first the Sioux and Cheyennes had seen only one body of troops, and supposed that all the soldiers were there together, but later, after the soldiers began to withdraw up the creek, they learned that more troops were up above. The Cheyennes believe that the Indian scouts from the troops intended to lead the pursuing Indians down between the two groups of soldiers, but made a mistake and went down the wrong ridge. These scouts were supposed to be Pawnees and Snakes; really they were Crows and Snakes. They killed a Snake who wore a spotted war bonnet. On the side from which the Indians charged a little ridge ran down toward the stream, and when they reached this ridge, they all dismounted and stopped there out of sight of the troops. Beyond was a smooth, level piece of ground. They did not stay there long, but started on toward the hills. Those who were out on the level ground were obliged to fight there, though there was little cover. After the Indians had got back out of sight of the soldiers, Two Moon looked over the ridge and saw four cavalry horses starting toward a hill. With Black Coyote he set out to capture them, and behind him followed two Cheyennes and then two Sioux. When they came in sight, charging down the hill, the soldiers came to meet them and drive them back. They began to shoot at the Indians and came near overtaking them. They almost caught them, but at last gave up the pursuit and rode back. The six men who had charged, when they saw that they could accomplish nothing, turned to join another body of Indians that was coming in above them. These were chiefly Cheyennes. Here two brave men, White Shield and a Sioux, charged on the troops, and all the Indians followed them. When the charge was made, the troopers were on foot, but as the Indians approached, they all mounted and retreated toward the main body of the troops. They did not run far, but wheeled, fell in line, fired a volley, and then mounted and ran back. Here White Shield killed a man and ran over and counted coup on him. The Sioux did the same. On a little ridge the soldiers again dismounted, trying to hold the Indians back, but the body coming against them was large; an officer was shot, and the troops retreated. Among them was a soldier who could not mount his horse. White Shield rode between him and his horse, to knock the reins out of his hands and free the horse. He did not get the horse, but counted coup on the man, who carried a bugle. When the Indians left the ridge from which the troops had been driven, they had to cross a steep gulch to get on the next flat. On the flat a soldier fell off his horse, perhaps wounded, and lost his horse. A Cheyenne named Scabby Eyelid rode up to the soldier and tried to strike him with his whip. The soldier caught the whip and pulled the Indian off his horse. They struggled together, but separated without serious hurt to either. Now the Indian scouts of the troops made a charge and the Sioux and Cheyennes ran, and retreated over the deep gulch which they had just crossed. After crossing this they wheeled and fired once and then again turned and ran. The number of soldiers behind them was large. The soldiers made a strong charge, but the Indians divided, some going down the ridge and some up. Young Two Moon left the ridge, and when he reached the flat his horse began to get tired, and close behind him and coming fast were the soldiers. Those Cheyennes who were up above could see there alone a person whose horse had given out. Two Moon thought that this was his last day. He was obliged to dismount, leave his horse, and run off on foot. The bullets were flying pretty thick and were knocking up the dust all about him. He saw coming before him a man who was riding on a buckskin horse and thought that he was going to have help, but the bullets flew so thick that the man who was coming turned and rode away. Again he saw a man coming toward him, riding a spotted horse. He recognized the person, Young Black Bird-now White Shield. White Shield rode up to his side and told him to jump on behind. In that way White Shield saved his life that day. They had not gone very far, but farther than he could have gone on foot, when this horse too began to lose its wind and to get tired. Soon they saw another man coming, leading a horse that he had captured from the Indian scouts who were with the troops. It was Contrary Belly. Meantime two Sioux had dashed up to the two men, but when they got close, one of them said: "They are Cheyennes," and they rode away. Then Contrary Belly came up, and Two Moon jumped on the led horse and rode off. When they reached the main body of Indians, the soldiers were still coming up, but there were so many Indians that they could not drive them. Here the fight stopped. The Cheyennes and Sioux remained there for a little while and then went away and left the soldiers. Many men had been wounded and many horses killed and wounded, so that many of the Indians were on foot. They left four men to watch the troops to see what they did. These four men were: Lost Leg, Howling Wolf, and two others. They saw the soldiers gather up the dead and bring them down near the creek not far from their camp. For this fight White Elk was given by his uncle, Mohk sta' ei ai no, his medicine, which was that of the swallow that has a forked taila barn swallow. On his war bonnet, low down on the tail of the bonnet, was tied the skin of a swallow, while the brow piece was painted with many butterflies and dragonflies, and on the side of the tailpiece of the war bonnet were eagle-down feathers four or five inches apart, and between each two feathers a tiny leaden bullet. Among the Cheyennes in this battle was Chief Comes in Sight, a brave man and a good fighter. His sister had followed him out to the battle. At the beginning of the fight he had charged the soldiers many times, and when they were fighting the upper group of soldiers, as he was riding up and down in front of the line, his horse was killed under him. White Elk was also riding up and down the line, but was going in the opposite direction from Chief Comes in Sight, and it was just after they had passed each other that Chief Comes in Sight was dismounted. Suddenly White Elk saw a person riding down from where the Indians were toward the soldiers, pass by Chief Comes in Sight, turn the horse and ride up by him, when Comes in Sight jumped on behind and they rode off. This was the sister of Chief Comes in Sight, Buffalo Calf Road Woman... The Cheyennes have always spoken of this battle by this name: In Cheyenne, it is: Young girl saved his life brother. Comes in Sight is still living in Oklahoma, about sixty-six years old. It was near where Comes in Sight was unhorsed that the Shoshoni with a spotted war bonnet was killed. White Elk expresses the opinion that in this fight there were perhaps ninety Cheyennes. He does not know how many Sioux may have been there. In the place where the hottest fighting occurred there were more Indians than soldiers, but this does not count the troops who were on the other side of the stream-about three troops of cavalry. The account of what White Shield saw and did in this battle is interesting, because it gives so well the Indian point of view and explains to some extent the Cheyenne belief in the help received from animals. White Shield's name at that time was Young Black Bird. He is the son of Spotted Wolf, one of the bravest of the old-time warriors of the Cheyennes, who has been dead for about twenty years. Spotted Wolf, when he heard the news that the soldiers were coming, said to White Shield: "My son, you had better tie up your horse. Do not let him fill himself with grass. If a horse's stomach is not full, he can run a long way; if his stomach is full, he soon gets tired. I wish to see you take the lead on this war trip." His father had been taught by the kingfisher bird and understood it. Spotted Wolf said further: "Son, go out and from one of the springs that come out of the hillside get me some blue clay." After it had been brought to him, he painted on the shoulders and hips of the horse the figure of a kingfisher with its head toward the front. "Now," he said, "your horse will not get out of wind. Take him down to the stream and give him plenty of water; all he will drink." When White Shield brought the horse back, his father said: "When you are ready to start, I will go with you, and before you make the charge, I will put some medicine on you." just before they left camp Spotted Wolf said: "Now, drink plenty of water and let this be your last drink until the fight is over." They started from camp after the sun was down and traveled all night, stopping from time to time. At daylight they were on the Rosebud at the mouth of Trail Creek. Above this they stopped and decided that as they were getting near to the enemy they would dress (paint) themselves here. His father dressed him, painting his whole body with yellow earth paint. Spotted Wolf had a bundle containing the war clothing that he himself was accustomed to wear in fights. From this bundle he took a scalp, and, placing the horse so that it faced toward the south, he tied the scalp to its lower jaw. He then put his own war shirt on White Shield, took his kingfisher (the stuffed skin of a kingfisher), and held it up to the sun and sang a song. "My son," he said, "this is the song sung to me when the spirits took pity on me. If the kingfisher dives into the water for a fish, he never misses his prey. Today I wish you to do the same thing. You shall count the first coup in this fight." After he had finished speaking, he tied the kingfisher to his son's scalp lock. Held in the bill of the kingfisher were some kingfisher's feathers, dyed red. The feathers represented the flash of a gun. Then he hung about his son's neck a whistle made of the bone from an eagle's wing. He said: "If anyone runs up to you to shoot you, make this noise [imitating the cry of the kingfisher] and the bullet will not hurt you." He took in his mouth a little medicine and a little earth and raised the right forefoot of the horse and blew a little of this on the sole of the hoof, and did the same thing on the right hind foot, the left hind foot, and the left forefoot. Then he blew the medicine on the horse between the ears, on the withers, at the end of the mane, and at the root and the end of the tail. "Putting this on the soles of his hoofs," said Spotted Wolf, "will make him carry himself lightly and not fall. When you come within sight of the enemy and are going to charge, put the whistle in your mouth and whistle. That is what the kingfisher does when he catches the fish. You shall catch one of the enemy. When you see the enemy, they may frighten you so that you will lose your mind a little, but I do not think this will happen. You will frighten your enemies before they frighten you. I have dressed you fully for war. There are some women with the party; you must not ride by the side of any of them. Give me your quirt, son." He took some horse medicine and rubbed it over the quirt and said: "If you see anyone ahead of you and whirl your quirt above your head, the man's horse may fall. When you charge, try to keep on the right-hand side of everyone. Take pity on everyone. If you see some man in a hard place, from which he cannot escape, help him if you can. If you yourself get in a bad place, do not get excited, but try to shoot and defend yourself. That is the way to become great. If you should be killed, the enemy when they go back will say that they fought a man who was very brave; that they had a hard time to kill him." Such were the instructions given White Shield by his father. Before this was finished, some of the Cheyennes had already gone forward, and a little later he heard shots-those fired by their own scouts who had met some Crow scouts. When the shots were heard, the Sioux and Cheyennes all charged, riding across the hills to where they heard the shooting, running up one hill and down another. They did not follow the stream valley. When they reached the place, the Indian scouts had retreated to the soldiers, who sat there on their horses. Old Red War Bonnet, Walks Last, Feathered Sun, White Shield, and White Bird were among the first to reach this point. The Sioux and Cheyennes were beginning to come toward the soldiers from all directions. At the top of the hill they stopped about six hundred yards from the soldiers. Suddenly to the right a man appeared charging toward the soldiers. He was followed by a little boy twelve or thirteen years old. They recognized Chief Comes in Sight, and the boy was a little Sioux boy. The five Cheyennes just mentioned charged down, following the two, and about fifty yards behind them. Neither the soldiers nor Indian scouts fired, but they kept moving about. When the Cheyennes were quite near to the soldiers, Chief Comes in Sight turned his horse to the left and the boy to the right. Chief Comes in Sight fired two shots from a pistol, and all the soldiers shouted and fired and charged. They began to overtake Chief Comes in Sight, who now joined the five Cheyennes, and all had to run. The Indian scouts chased the little boy and overtook him, taking him from his horse and killing him. As the six Cheyennes went back to the hill they had been on, the soldiers almost overtook them. When the soldiers were within fifty yards of them, Feathered Sun said: "Let us dismount; they are pushing us too closely." Feathered Sun and White Shield dismounted and the troops stopped, all except one scout, thought to be a Crow. He carried a long lance and, lying down on his horse's back so that he could not be seen, charged straight toward the two. White Shield and the other man were some distance apart and the Crow was coming straight for White Shield. He was obliged to shoot at the horse, aiming at its breast. When he fired, the horse turned a somersault, turning clear over. The Crow dropped his lance and White Shield rushed to his own horse, and as he mounted, it was like a wave of water coming over the hill behind him-the Cheyennes. They seemed to come from all the foothills and now the soldiers fell back. When the Cheyennes and Sioux charged down, they were less than fifty yards from the troops. White Shield turned his horse and rode along in front of the Indian scouts, who were all on foot and shooting. A little off to one side the soldiers were fighting the Cheyennes and Sioux. As he rode along, he saw a man who had been shot and who was wearing a large war bonnet. The Cheyennes tried to count coup on the body, but the scouts fought for it. Here a Sioux had his leg smashed and a Cheyenne's horse was killed. White Shield got to within three or four yards of the body, but he was obliged to turn his horse. As he looked down, he saw a troop of cavalry galloping toward them, but not yet shooting. When they had come pretty near, the soldiers began to fire, and the Cheyennes and Sioux retreated to the hills. The Indian scouts and the soldiers made a strong charge, and were right behind the Cheyennes and Sioux, who were forced to whip their horses on both sides to get away. It was a close race. The soldiers were shooting fast. Some men called out: "Stop, stop, some horses have been killed; let us save these men and stand off the soldiers." They did not stop, but they succeeded in saving all the dismounted men. The troops chased the Indians to a steep ravine which the horses could not cross. Those who reached it first dismounted. When they reached here, two more companies of soldiers came up. Before they came to the ravine, the ground dropped off a little, making a ridge behind which the Sioux and Cheyennes stopped, and all dismounted. This made them feel good, for here was something to fight behind. They were about two hundred men. At this time three separate fights were going on, of which this was the one in the middle. At this place they shot down the horse of one of the scouts, and when this horse fell, the soldiers and scouts turned back, and the Cheyennes and Sioux mounted and charged them. They followed them back to the place where they had fought for the man with the war bonnet. On the way back they overtook a scout on a wounded horse. He was a Shoshoni. He threw himself off his horse and ran ahead on foot. Two Sioux were close behind him and White Shield was off to one side. One Sioux carried a long lance, and as the Shoshoni turned to fire, he struck him with his lance, and afterward with the body of his horse he knocked him down. As the Shoshoni was getting up, the second Sioux ran over him with his horse, and then White Shield came up and shot him, but counted no coup. The soldiers and scouts charged back on them, and followed them back to the place where they had been before, at the edge of the ravine. All this time the firing was heavy on both sides. When the Cheyennes and Sioux had run behind the ridge again, they stood with about half the body exposed, shooting over it. A Cheyenne standing by White Shield was shot through the body, but did not die until they got him to camp. For a long time, on a little flat a quarter of a mile wide, they fought there, each side alternately retreating and advancing. Far off to the right they could hear shooting which sounded as if it were going up into the hills. After a time White Shield left this fight and rode off to one side to get into this other fight. When he rode his horse up on the hill, he could see the fight; one company of soldiers following up some Indians. The soldiers had left their horses and were advancing on foot. Their horses were a quarter of a mile behind them. Riding up and down before the soldiers, he saw a young man whom he at length recognized as Goose Feather, a son of the chief, Dull Knife. White Shield rode on until he met Goose Feather, who had gone behind a little knoll. He said to Goose Feather, "Hold my horse for a moment," and he stepped over the hill in sight. As he did this, all the soldiers threw themselves on the ground and began firing, but he managed to jump behind a rock so as to be out of sight.. Then the soldiers turned their guns and began to shoot in another direction at the Indians on the hill. White Shield shot at the nearest soldier, who was about forty yards off, but shot under him, throwing the dirt over his body. The soldiers now all rose to their feet to go back to their horses, and the nearest soldier, having partly turned, ran, and White Shield shot at him and he fell. White Shield ran back to get his horse, but Goose Feather had let it go so that he might run down and count coup on the soldier. White Shield caught his horse, but Goose Feather reached the soldier first, and counted coup on him with a lance, while White Shield counted the second coup with his whip. The third man to count coup took the soldier's arms and belt. The soldiers kept on running toward their horses. White Shield and Goose Feather went on after the soldiers. Just as the soldiers reached their horses, an officer called out giving an order, and all the soldiers faced about to meet the charge of a great crowd of Cheyennes who were following. White Shield turned off to the right and got behind a little knoll. Every Cheyenne and Sioux dodged behind the knoll, and now both sides were shooting as hard as they could, only about thirty yards apart. All at once the soldiers ceased firing, but the Indians kept on shooting. White Shield crept over the hill to look and see why the soldiers had stopped. The horses were all in line, and the soldiers had one foot in the stirrup. Off to one side a man was seated on a roan horse, who gave an order and then turned to look back. White Shield shot just as he turned his head, and when they found the man, he was shot just over the eyebrow. The soldiers started to retreat, and as they did so, they scattered. A man on foot, holding his horse with one hand and a six-shooter in the other, was trying to mount his horse. White Shield made a charge to count coup on him. The man shot as White Shield was coming up, but the horse pulled him, and he missed his aim. White Shield rode his horse between the man and the horse he was holding, and knocked the man down with his gun. The next man behind White Shield rode over the soldier. White Shield turned his horse and rode back to the officer he had killed, and as he was going, he saw some guns. When he came back, the guns were gone, but the officer still had a six-shooter and a belt full of pistol cartridges. White Shield took the six-shooter. As he looked back, he saw the soldier that he had knocked down creeping about on his hands and knees and went back and killed him. He took his belt and cartridges, but his six-shooter was gone. At this place White Shield stopped and got off his horse and led it up and down. At a distance he could see the people fighting. The soldiers had separated and were split up in twos and threes. Far off he could see a great many soldiers and the scouts. As he kept looking, presently he saw a person riding toward the soldiers, and then he saw his horse fall, catching the man under its body. He seemed to be trying to get out, but the scouts rode up and shot him. After the man was shot, all the Indians ran, and the soldiers followed them back to the place from which the Indians had driven the soldiers, and now the Indians had to scatter out by twos and threes. White Shield did not move from the place where he was until the Indians got up to him. Then he mounted. Some of those who came up to him were riding double-men whose horses had been shot or had given out. Still he waited, thinking he would have a chance to get in some more shots. He fired a shot or two, and then looking down to one side, he saw a man on foot and soldiers following and overtaking him. When he tried to open his gun after firing, he could not open it. He had put in a captured cartridge, too small for the gun, and it had swelled and stuck in the chamber. He was unarmed. By this time the people had all passed and the only man between him and the soldiers was the one on foot. He rode down to this man, and found him almost exhausted. It was young Two Moon. White Shield called out to him: "My friend, come and get on behind me." The remainder of the Indians were a long way ahead of them. He said to Two Moon: "I can no longer shoot; I have a shell fast in my gun." Many Indians ahead of them were now on foot, and many horses were constantly being shot and wounded or were giving out and stopping. Here Feathered Sun's horse was shot, and its rider jumped up and ran along on foot. The soldiers were close behind-only about thirty yards. Another man on foot was running along behind Feathered Sun, and just as he reached Feathered Sun's horse, which had been knocked down, it got up on its feet, and he jumped on it and it ran off as well as ever. It had only been creased. Down the line a man was seen coming, and when he got near, they saw it was Contrary Belly. He was leading a roan horse, and as he overtook them he said: "Here is a horse for you to ride"; and Two Moon took it. As White Shield rode on, he saw in front of him a Sioux on horseback and another Sioux on foot carrying a stick in his hand. He rode up to the man on foot and saw that he was carrying a ramrod, for he had been using a muzzle-loader, and with this ramrod White Shield knocked the shell out of his gun. Meantime, the soldiers and the Indian scouts behind them were seeing how much noise they could make with guns and cries, and the Cheyennes and Sioux in front were running and stopping and firing and running. The Sioux on horseback had on a war bonnet and shield. As he rode, his horse's leg was broken. He would not leave his horse, but stopped to fight, and then turned and ran to some timber. The soldiers and scouts all seemed to follow him and this gave the other Indians a chance to get away. The soldiers killed the Sioux, and then all turned back. The Cheyennes and Sioux watched them a long time from the hills, and then went to their camps. When White Shield's gun was made useless by the shell, he never once thought of the six-shooter he had captured. He might have been killed wearing this without attempting to defend himself. When they got down on the Little Big Horn River, they began to have war dances. They took out the buffalo hat and hung it up and then danced, tying a scalp to it. For four nights of this dance his mother carried the gun that he had used. At the Big Bend of the Rosebud, where the lower group of soldiers was, is now the farm of Thomas Benson. The battleground on the river above his ranch includes the farms of J. L. Davis, A. L. Young, and Charles Young. On a little stream running into the Rosebud below where the fight with the upper group of soldiers took place is Mrs. Colmar's, and on the south prong of the Rosebud lives M. T. Price. Ranches and cultivated fields occupy the ground fought over by the white troops and Indians in 1876. The camp of the soldiers was on land now belonging to Mr. Benson. There the dead were buried. It was on the ground between the Big Bend and the Young places that the fighting took place. It was all on the open prairie above, or in the wide open valley. There was no chance for ambush or approach under cover. In the hot fighting and the fierce charges made, much courage was displayed by Indians and whites alike. The Fighting Cheyennes by George Bird Grinnell, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, NY 1915 p 328 - 344

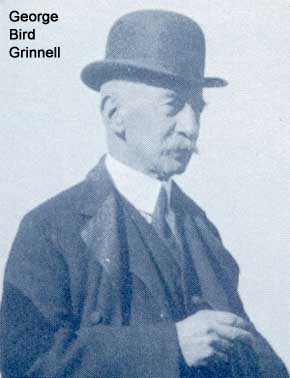

In his long and distinguished career, George Bird Grinnell was a naturalist with George Custer's 1874 Black Hills expedition, founded of the Audubon Society and was the author of The Fighting Cheyenne. Although not a Cheyenne, or an eye-witness to the battle of the Little Bighorn, George Bird Grinnell shares a crucial quality with the other Sioux, Cheyenne and Crow chroniclers included in 100 Voices. Like Ohiyesa, John Stands In Timber, William Bordeaux, Pretty Shield, Bird Horse and David Humphreys Miller, Grinnell had unique access to important particpants in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. What you see in The Fighting Cheyenne is an intelligent, well-informed and sympathetic telling of the Cheyenne story. Here is Grinnell's chapter on the Battle of the Little Bighorn from The Fighting Cheyenne, and here is his account of Little Horse stripping the corpse of an officer, probably Thomas Custer. -- B.B.

|

||||||||||||

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL'S STORY

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL'S STORY