|

|||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... John Finerty's Story of the Battle

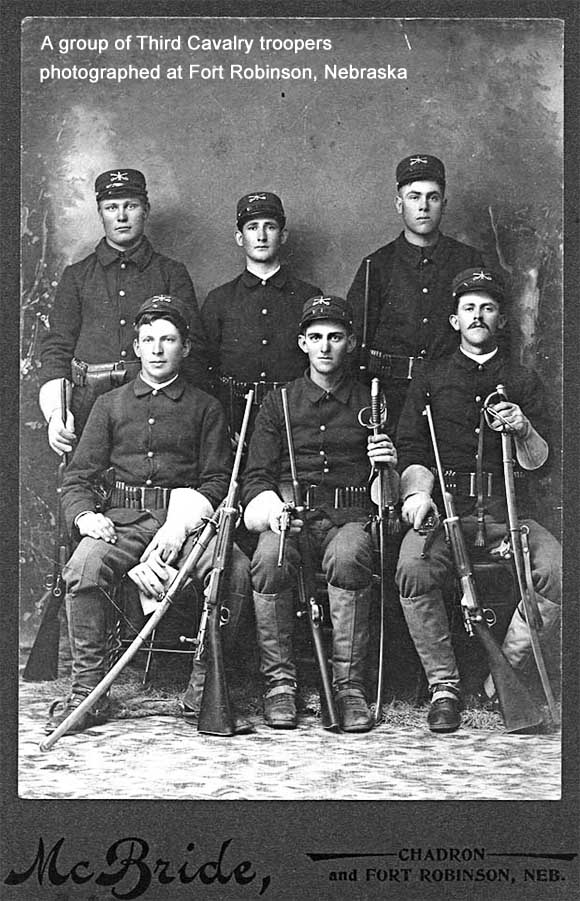

THE BATTLE OF THE ROSEBUD DAWN HAD not yet begun to tinge the horizon above the eastern bluffs, when every man of the expedition was astir. How it came about, I know not, but I suppose each company commander was quietly notified by the headquarters' orderlies to get under arms. Low cooking fires were allowed to be kindled, so that the men might have coffee before moving further down the canon, and every horse and mule was saddled and loaded with military dispatch. The Indians, having digested their buffalo hump banquet of the previous night, were quite alert, but prepared to go on with another feast. The General, however, sent his half-breed scouts to inform them that they must hurry up and go forward. The Snakes, to their credit be it recorded, obeyed with some degree of martial alacrity, but the Crows seemed to act very reluctantly. It was evident that both tribes had a very wholesome respect for Sioux prowess. I noticed, among other things, that the singing had ceased, and it was quite apparent that the gentle savages began to view the coming conflict with feelings the reverse of hilarious. They got their war-horses ready, looked to their arms, and at last in the dim morning light, a large party left camp and speedily disappeared over the crests of the northern bluffs. The soldiers, with their horses and mules saddled up and bridled, awaited the order to move forward with that warlike impatience peculiar to men who prefer to face danger at once, rather than be on the lookout for it everlastingly. They were as cheerful as ever, joked with each other in low tones, and occasionally borrowed or lent a chew of tobacco in order to kill time. A few of the younger men grasping the pommels of their saddles, and leaning their heads against their horses, dropped off into a cat nap. Presently we saw the infantry move out on their mules, and within a few minutes the several cavalry battalions were properly marshaled and all were moving down the valley in the gray dawn, with the regularity of a machine, complicated, but under perfect control. We marched on in this fashion, the cavalry finally outstripping the infantry, halting occasionally, until the sun was well above the horizon. At about 8 o'clock we halted in a valley, very similar in formation to the one in which we had pitched our camp the preceding night. Rosebud Stream, indicated by the thick growth of wild roses, or sweet brier, from which its name is derived, flowed sluggishly through it, dividing it from south to north into two almost equal parts. The hills seemed to to rise on every side, and we were within easy musket shot of those most remote. Our horses were rather tired from the long march of the 16th, and orders came to unsaddle and let them graze. Our battalion (Mills') occupied the right bank of the creek with the 2d Cavalry, while on the left bank were the infantry and Henry's and Van Vliet's battalions of the 3d Cavalry. The pack train was also on that side of the stream, together with such of the Indians as did not move out before daybreak to look for the Sioux, whom they were by no means anxious to find. The young warriors of the two tribes were running races with their ponies, and the soldiers in their vicinity were enjoying the sport hugely. The sun became intensely hot in that close valley, so I threw myself upon the ground, resting my head upon my saddle. Captain Sutorius, with Lieutenant Von Leutwitz, who had been transferred to Company E, sat near me smoking. At 8:30 o'clock, without any warning, we heard a few shots from behind the bluffs to the north. "They are shooting buffalo over there," said the Captain. Very soon we began to know, by the alternate rise and fall of the reports, that the shots were not all fired in one direction. Hardly had we reached this conclusion, when a score or two of our Indian scouts appeared upon the northern crest, and rode down the slopes with incredible speed. "Saddle up, there-saddle up, there, quick!" shouted Colonel Mills, and immediately all the cavalry within sight, without waiting for formal orders, were mounted and ready for action. General Crook, who appreciated the situation, had already ordered the companies of the 4th and 9th Infantry, posted at the foot of the northern slopes, to deploy as skirmishers, leaving their mules with the holders. Hardly had this precaution been taken when the flying Crow and Snake scouts, utterly panic stricken, came into camp shouting at the top of their voices, "Heap Sioux! Heap Sioux!" gesticulating wildly in the direction of the bluffs which they had abandoned in such haste. All looked in that direction and there, sure enough, were the Sioux in goodly numbers and in loose, but formidable, array. The singing of the bullets above our heads speedily convinced us that they had called on business. I looked along the rugged, stalwart line of our company and saw no coward blanching in any of the bronzed faces there. "Why the h--l don't they order us to charge?" asked the brave Von Leutwitz. "Here comes Lemley (the regimental adjutant) now," answered Sutorius. "How do you feel about it, eh?" he inquired, turning to me. "It is the anniversary of Bunker Hill," was my answer. "The day is of good omen." "By Jove, I never thought of that," cried Sutorius, and (loud enough for the soldiers to hear) "It is the anniversary of Bunker Hill, we're in luck." The men waved their carbines, which were right shouldered, but true to the parade etiquette of the American army did not cheer, although they forgot all about the etiquette later on. Up, meanwhile, bound on bound, his gallant horse covered with foam, came Lemley. "The commanding officer's compliments, Colonel Mills!" he yelled. "Your battalion will charge those bluffs on the center." Mills immediately swung his fine battalion, consisting of Troops A, E, I and M, by the right into line, and rising in his stirrups shouted "Charge!" Forward we went at our best pace to reach the crest occupied by the enemy, who, meanwhile, were not idle, for men and horses rolled over pretty rapidly as we began the ascent. Many horses, owing to the rugged nature of the ground, fell upon their riders without receiving a wound. We went like a storm, and the Indians waited for us until we were within fifty paces. We were going too rapidly to use our carbines, but several of the men fired their revolvers, with what effect I could neither then, nor afterward, determine, for all passed like a flash of lightning, or a dream. I remember, though, that our men broke into a mad cheer as the Sioux, unable, to face that impetuous line of the warriors of the superior race, broke and fled with what white men would consider undignified speed. Out of the dust of the tumult, at this distance of time, I remember how well our troops kept their formation, and how gallantly they sat their horses as they galloped fiercely up the rough ascent. We got that line of heights, and were immediately dismounted and formed in open order, as skirmishers, along the rocky crest. While Mills' battalion was executing the movement described, General Crook ordered the 2d Battalion of the 3d Cavalry, under Col. Guy V. Henry, consisting of Troops B, D, F and L, to charge the right of the Sioux array, which was hotly pressing our steady infantry. Henry executed the order with characteristic dash and promptitude, and the Indians were compelled to fall back in great confusion all along the line. General Crook kept the five troops of the 2d Cavalry, under Noyes, in reserve, and ordered Troops C and G of the 3d Cavalry under Captain Van Vliet and Lieutenant Crawford, to occupy the bluffs on our left rear, so as to check any movement that might be made by the wily enemy from that direction. Those bluffs were somewhat loftier than the eminences occupied by the rest of our forces, and Crawford told me, subsequently, that a splendid view of the fight was obtained from them. General Crook divined that the Indian force before him was a strong body -- not less perhaps than 2,500 warriors -- sent out to make a rear guard fight, so as to cover the retreat of their village, which was situated at the other end of the canyon. [Note: Crook and Finerty were both incorrect on this point. There was no village. In fact, Crazy Horse's plan was to destroy Crook in open combat, and if that failed, to retreat so that he trapped Crook's forces in the canyon, as Bourke correctly noted.] He detached Troop I of the 3d Cavalry, Captain Andrews and Lieutenant Foster, from Mills to Henry, after the former had taken the first line of heights. He reinforced our line with the friendly Indians, who seemed to be partially stampeded, and brought up the whole of the 2d Cavalry within supporting distance. The Sioux, having rallied on the second line of heights, became bold and impudent again. They rode up and down rapidly, sometimes wheeling in circles, slapping an indelicate portion of their persons at us and beckoning us to come on. One chief, probably the late lamented Crazy Horse, directed their movements by signals made with a pocket mirror or some other reflector. Under Crook's orders, our whole line remounted, and after another rapid charge we became masters of the second crest. When we got there, another just like it rose on the other side of the valley. There, too, were the savages, as fresh, apparently, as ever. We dismounted accordingly, and the firing began again. It was now evident that the weight of the fighting was shifting from our front, of which Major Evans had general command, to our left where Royall and Henry cheered on their men. Still the enemy were thick enough on the third crest, and Colonel Mills, who had active charge of our operations, wished to dislodge them. The volume of fire, rapid and ever increasing, came from our left. The wind freshened from the west, and we could hear the uproar distinctly. Soon, however, the restless foe came back upon us, apparently reinforced. He made a vigorous push for our center down some rocky ravines, which gave him good cover. Just then a tremendous yell arose behind us, and along through the intervals of our battalions came the tumultuous array of the Crow and Shoshone Indians, rallied and led back to action by Maj. George M. Randall and Lieut. John G. Bourke, of General Crook's staff. Orderly Sergeant John Van Moll of Troop A, Mills' battalion, a brave and gigantic soldier, who was subsequently basely murdered by a drunken mutineer of his company, dashed forward on foot with them. The two bodies of savages, all stripped to the breech-clout, moccasins, and war bonnet, came together in the trough of the valley, the Sioux having descended to meet our allies with right good will. All except Sergeant Van Moll were mounted. Then began a most exciting encounter. The wild foemen, covering themselves with their horses while going at full speed, blazed away rapidly. Our regulars did not fire because it would have been sure death to some of the friendly Indians, who were barely distinguishable by a red badge which they carried. Horses fell dead by the score-they were heaped there when the fight closed -but, strange to relate, the casualties among the warriors, including both sides, did not certainly exceed five and twenty. The whooping was persistent, but the Indian voice is less hoarse than that of the Caucasian, and has a sort of wolfish bark to it, doubtless the result of heredity, because the Indians, for untold ages, have been imitators of the vocal characteristics of the prairie wolf. The absence of very heavy losses in this combat goes far to prove the wisdom of the Indian method of fighting. Finally the Sioux on the right, hearing the yelping and firing of the rival tribes, came up in great numbers, and our Indians, carefully picking up their wounded and making their uninjured horses carry double, began to draw off in good order. Sergeant Van Moll was left alone on foot. A dozen Sioux dashed at him. Major Randall and Lieutenant Bourke, who had probably not noticed him in the general melee, but who, in the crisis, recognized his stature and his danger, turned their horses to rush to his rescue. They called on the Indians to follow them. One small, misshapen Crow warrior, mounted on a fleet pony, outstripped all others. He dashed boldly in among the Sioux, against whom Van Moll was dauntlessly defending himself, seized the big sergeant by the shoulder and motioned him to jump up behind. The Sioux were too astonished to realize what had been done until they saw the long-legged sergeant, mounted behind the little Crow, known as Humpy, dash toward our lines like the wind. Then they opened fire, but we opened also, and compelled them to seek higher ground. The whole line of our battalion cheered Humpy and Van Moll as they passed us on the home-stretch. There were no insects on them, either. In order to check the insolence of the Sioux we were compelled to drive them from the third ridge. Our ground was more favorable for quick movements than that occupied by Royall, who found much difficulty in forcing the savages in his front -- mostly the flower of the brave Cheyenne tribe -- to retire. One portion of his line under Captain Vroom pushed out beyond its supports, deceived by the rugged character of the ground, and suffered quite severely. In fact, the Indians got between it and the main body, and nothing but the coolness of its commander and the skillful management of Colonels Royall and Henry saved Troop L of the 3d Cavalry from annihilation on that day. Lieutenant Morton, one of Colonel Royall's aids, Captain Andrews, and Lieutenant Foster of Troop 1, since dead, particularly distinguished themselves in extricating Vroom from his perilous position. In repelling the audacious charge of the Cheyennes upon his battalion, the undaunted Colonel Henry, one of the most accomplished officers in the army, was struck by a bullet which passed through both cheek bones, broke the bridge of his nose, and destroyed the optic nerve in one eye. His orderly, in attempting to assist him, was also wounded, but temporarily blinded as he was and throwing blood from his mouth by the handful, Henry sat his horse for several minutes in front of the enemy. He finally fell to the ground, and as that portion of our line, discouraged by the fall of so brave a chief, gave ground a little, the Sioux charged over his prostrate body, but were speedily repelled, and he was happily rescued by some soldiers of his command. Several hours later, when returning from the pursuit of the hostiles, I saw Colonel Henry lying on a blanket, his face covered with a bloody cloth, around which the summer flies were buzzing fiercely, and a soldier keeping the wounded man's horse in such a position as to throw the animal's shadow upon the gallant sufferer. There was absolutely no other shade in that neighborhood. When I ventured to condole with the Colonel he merely said, in a low but firm voice, "It is nothing. For this are we soldiers!" and forthwith he did me the honor of advising me to join the army! Colonel Henry's sufferings, when our retrograde movement began, and, in fact, until-after a jolting journey of several hundred miles by mule litter and wagon-he reached Fort Russell, were horrible, as were, indeed, those of all the wounded. As the day advanced, General Crook became tired of the indecisiveness of the action and resolved to bring matters to a crisis. He rode up to where the officers of Mills' battalion were standing or sitting behind their men, who were prone on the skirmish line, and said, in effect, "It is time to stop this skirmishing, Colonel. You must take your battalion and go for their village away down the canon." "All right, sir," replied Mills, and the order to retire and remount was given. The Indians, thinking we were retreating, became audacious and fairly hailed bullets after us, wounding several soldiers. One man, named Harold, received a singular wound. He was in the act of firing, when a bullet from the Indians passed along the barrel of his carbine, glanced around his left shoulder, traversed the neck, under the skin, and finally lodged in the point of his lower jaw. The shock laid him low for a moment but, picking himself up, he had the nerve to reach for his weapon, which had fallen from his hand, and bore it with him off the ground. Our men, under the eyes of the officers, retired in orderly time, and the whistling of the bullets could not induce them to forget that they were American soldiers. Under such conditions, it was easy to understand how steady discipline can conquer mere numbers. Troops A, E, and M of Mills' battalion, having remounted, guided by the scout Grouard, plunged immediately into what is called, on what authority I know not, the Dead Canon of Rosebud Valley. It is a dark, narrow, and winding defile, over a dozen miles in length, and the main Indian village was supposed to be situated in the north end of it. Lieutenant Bourke of Crook's staff accompanied the column. A body of Sioux posted on a bluff which commanded the west side of the mouth of the canon was brilliantly dislodged by a bold charge of Troop E under Captain Sutorius and Lieutenant Von Leutwitz. After this our march began in earnest. The bluffs on both sides of the ravine were thickly covered with rocks and fir trees, thus affording ample protection to an enemy and making it impossible for our cavalry to act as flankers. Colonel Mills ordered the section of the battalion moving on the east side of the cafion to cover their comrades on the west side, if fired upon, and vice versa. This was good advice and good strategy in the position in which we were placed. We began to think our force rather weak for so venturous an enterprise, but Lieutenant Bourke informed the Colonel that the five troops of the 2d Cavalry under Major Noyes were marching behind us. A slight rise in the valley enabled us to see the dust stirred up by the supporting column some distance in the rear. The day had become absolutely perfect, and we all felt elated, exhilarated as we were by our morning's experience. Nevertheless, some of the more thoughtful officers had their misgivings, because the cafion was certainly a most dangerous defile where all the advantage would be on the side of the savages. General Custer, although not marching in a position so dangerous and with a force nearly equal to ours, suffered annihilation at the hands of the same enemy about eighteen miles further westward only eight days afterward. Noyes, marching his battalion rapidly, soon overtook our rear guard, and the whole column increased its pace. Fresh signs of Indians began to appear in all directions, and we began to feel that the sighting of their village must be only a question of a few miles further on. We came to a halt in a kind of cross canon, which had an opening toward the west, and there tightened up our horse girths and got ready for what we believed must be a desperate fight. The keen-eared Grouard pointed toward the occident, and said to Colonel Mills, "I hear firing in that direction, sir." Just then there was a sound of fierce galloping behind us and a horseman dressed in buckskin and wearing a long beard, originally black but turned temporarily gray by the dust, shot by the halted command and dashed up to where Colonel Mills and the other officers were standing. It was Maj. A. H. Nickerson of the General's staff. He has been unfortunate since, but he showed himself a hero on that day at least. He had riden, with a single orderly, through the canyon to overtake us, at the imminent peril of his life. "Mills," he said, "Royall is hard pressed and must be relieved. Henry is badly wounded, and Vroom's troop is all cut up. The General orders that you and Noyes defile by your left flank out of this canon and fall on the rear of the Indians who are pressing Royall." This, then, was the firing that Grouard had heard. Crook's order was instantly obeyed, and we were fortunate enough to find a comparatively easy way out of the elongated trap into which duty had led us. We defiled, as nearly as possible, by the heads of companies in parallel columns so as to carry out the order with greater celerity. We were soon clear of Dead Canyon, although we had to lead our horses carefully over and among the boulders and fallen timber. The crest of the side of the ravine proved to be a sort of plateau, and there we could hear quite plainly the noise of the attack on Royall's front. We got out from among the loose rocks and scraggy trees that fringed the rim of the gulf and found ourselves in quite an open country. "Prepare to mount-mount!" shouted the officers, and we were again in the saddle. Then we urged our animals to their best pace and speedily came in view of the contending parties. The Indians had their ponies, guarded mostly by mere boys, in rear of the low, rocky crest which they occupied. The position held by Royall rose somewhat higher, and both lines could be seen at a glance. There was very heavy firing and the Sioux were evidently preparing to make an attack in force, as they were riding in by the score, especially from the point abandoned by Mills' battalion in its movement down the cafion, and which was partially held thereafter by the friendly Indians, a few infantry, and a body of sturdy mule packers, commanded by the brave Tom Moore, who fought on that day as if he had been a private soldier. Suddenly the Sioux lookouts observed our unexpected approach, and gave the alarm to their friends. We dashed forward at a wild gallop, cheering as we went, and I am sure we were all anxious at that moment to avenge our comrades of Henry's battalion. But the cunning savages did not wait for us. They picked up their wounded, all but thirteen of their dead, and broke away to the northwest on their fleet ponies, leaving us only the thirteen scalps, 150 dead horses and ponies, and a few old blankets and war bonnets as trophies of the fray. Our losses, including the friendly Indians, amounted to about fifty, most of the casualties being in the 3d Cavalry, which bore the brunt of the fight on the Rosebud. Thus ended the engagement which was the prelude to the great tragedy that occurred eight days later in the neighboring valley of the Little Big Horn. The General was dissatisfied with the result of the encounter because the Indians had clearly accomplished the main object of their offensive movement -- the safe retreat of their village. [Note: again, neither Crook nor Finerty had a clue about the significance of what had just happened. In fact, Crazy Horse and the Sioux / Cheyenne force he commanded won a smashing strategic victory at the Battle of the Rosebud, a victory which eliminated Crook from the campaign and set up everything that was to follow with Custer on the Little Bighorn.] Yet he could not justly blame the troops who, both officers and men, did all that could be done under the circumstances. We had driven the Indians about five miles from the point where the fight began and the General decided to return there in order that we might be nearer water. The troops had nearly used up their rations and had fired about 25,000 rounds of ammunition. It often takes an immense amount of lead to send even one Indian to the happy hunting grounds. The obstinacy, or timidity, of the Crow scouts in the morning spoiled General Crook's plans. [Note: scout Frank Grouard says just the opposite: that Crook's Indian Auxiliary's probably saved the American forces from annhilation on Crazy Horse's initial charge.] It was originally his intention to fling his whole force on the Indian village and win or lose all by a single blow. The fall of Guy V. Henry early in the fight on the left had a bad effect upon the soldiers, and Captain Vroom's company became entangled so badly that a temporary success raised the spirits of the Indians and enabled them to keep our left wing in check sufficiently long to allow the savages to effect the safe retreat of their village to the valley of the Little Big Horn. Had Crook's original plan been carried out to the letter, our whole force -- about 1,100 men -- would have been in the hostile village at noon, and in the light of after events it is not improbable that all of us would have settled there permanently. Five thousand able-bodied warriors, well armed, would have given Crook all the trouble he wanted, if he had struck their village. I am bound to add, for the honor of the journalistic profession, that Mr. McMillan, who accompanied our battalion, showed marked gallantry throughout the affair, which lasted from 8 in the morning until 2 in the afternoon, and the officers with the other commands spoke warmly that evening of the courage displayed by Messrs. Strahorn, Wasson, and Davenport. Our wounded were placed on extemporized travois, or mule litters and our dead were carried on the backs of horses to our camp of the morning, where they received honorable burial. Nearly all had turned black from the heat, and one soldier, named Potts, had not less than a dozen Indian arrows sticking in his body. This resulted from the fact that he was killed nearest to the Indian position and the young warriors had time to indulge their barbarity before the corpse was rescued. One young Shoshone Indian, left in the rear to herd the horses of his tribe, was killed by a small party of daring Cheyennes, who during the heat of Royall's fight rode in between that officer's left and the right of Van Vliet. The latter supposed that the adventurous savages were some of our redskins, so natural and unconcerned were all their actions. The Cheyennes slew the poor boy with their tomahawks, took his scalp, leaving not a wrack behind, and drove away a part of his herd. Van Vliet, as the marauders were returning, had his suspicions aroused and ordered Crawford's men to fire upon them. This they did with such good effect that the raiders were glad to drop the captured ponies and make off in a hurry, having lost one man killed (we found the body next day) and several wounded. During the severest portion of the conflict General Crook's black charger was wounded under him. Lieutenant Lemley's horse was also hurt and rendered unfit for further service. Lieutenants Morton and Chase of the 3d Cavalry did good service throughout the conflict, and narrowly escaped death while riding from one point of the line to the other. Lieutenant Lemley came near losing his scalp by riding close up to a party of hostile Indians whom he supposed were Crows. His escape was simply miraculous. In fact, in most cases it was difficult to tell our redskins from those of Sitting Bull. There is a strong family resemblance between all of them. We went into camp at about 4 o'clock and were formed in a circle around our horses and pack train, as on the previous night. The hospital was established under the trees down by the sluggish creek, and there the surgeons exercised their skill with marvelous rapidity. Most of the injured men bore their sufferings stoically enough, but an occasional groan or half-smothered shriek would tell where the knife, or the probe, had struck an exposed nerve. The Indian wounded -- some of them desperate cases -- gave no indication of feeling, but submitted to be operated upon with the grim stolidity of their race. General Crook decided that evening to retire on his base of supplies-the wagon train-with his wounded, in view of the fact that his rations were almost used up and that his ammunition had run pretty low. He was also convinced that all chance of surprising the Sioux camp was over for the present, and perhaps he felt that even if it could be surprised his small force would be unequal to the task of carrying it by storm. The Indians had shown themselves good fighters, and he shrewdly calculated that his men had been opposed to only a part of the wellarmed warriors actually in the field. During the night a melancholy wailing arose from the Snake camp down by the creek. They were waking the young warrior killed by the Cheyennes that morning, and calling upon the Great Spirit for vengeance. I never heard anything equal to the despairing cadence of that wail, so savage and so dismal. It annoyed some of the soldiers, but it had to be endured. The bodies of our slain were quietly buried within the limits of the camp, and every precaution was taken to obliterate the traces of sepulture. The Sioux did not disturb us that night. There was no further need for precaution as to signals, and at 4 o'clock on the morning of Sunday, June 18th, the reveille sounded. All were immediately under arms, except the Snake Indians, who had deferred the burial of their comrade until sunrise. All the relatives appeared in black paint, which gave them a diabolical aspect. I had been led to believe that Indians never yielded to the weakness of tears, but I can assure my readers that the experience of that morning convinced me of my error. The men of middle age alone restrained their grief, but the tears of the young men and of the squaws rolled down their cheeks as copiously as if the mourners had been of the Caucasian race. I afterward learned that the sorrow would not have been so intense if the boy had not been scalped. There is some superstition connected with that process. I think it had reference to the difficulty of the admission of the lad's spirit, under such circumstances, to the happy hunting grounds. A grave was finally dug for the body in the bed of the stream, and at a point where the horses had crossed and re-crossed. After the remains were properly covered, a group of warriors on horseback rode over the site several times, thus making it impossible for the Sioux to find the body. This ceremony ended, our retreat began in earnest. Our battalion was, as nearly as I can remember, pretty well toward the head of the column. Between us and the 2d Cavalry came the wounded, on their travois, and behind them came the mounted infantry. Looking backward occasionally, we could see small parties of Sioux watching us from the bluffs, but they made no offensive movement. As I rode along with Sutorius and Von Leutwitz I observed a crowd of Crow Indians dismounted and standing around some object which lay in the long grass some distance to our right. The Lieutenant and I rode over there and saw the body of a stalwart Sioux warrior, stiff in death, with the mark of a bullet wound in his broad bosom. The Crows set to work at once to dismember him. One scalped the remains. Another cut off the ears of the corpse and put them in his wallet. Von Leutwitz and I remonstrated, but the savages only laughed at us. After cutting off toes, fingers, and nose, they proceeded to indecent mutilation, and this we could not stand. We protested vigorously, and the Captain, seeing that something singular was in progress, rode up with a squad of men and put an end to the butchery. One big, yellow brute of a Crow, as we rode off, took a portion of the dead warrior's person out of his pouch, waved it in the air, and shouted something in broken English which had reference to the grief the Sioux squaws must feel when the news of the unfortunate brave's fate would reach them. And then the whole group of savages burst into a mocking chorus of laughter that might have done honor to the devil and his angels. I lost all respect for the Crow Indians after that episode, I concluded, and I think with justice, that they are mostly braggarts in peace and laggards in war. As we continued our march, having rejoined the head of the column, we heard a great rattling of small arms in the rear and concluded we had been attacked. The whole command halted, and then we saw what the trouble was. A solitary and much frightened antelope had broken from cover far toward the rear, and ran directly along our flank for more than a mile. Although at least five hundred men fired at the nimble creature, it ran the gauntlet in safety and at last found refuge in the thick timber of a small stream which we were obliged to cross. Owing to the condition of the wounded, we were ordered to halt in an excellent camping place several miles from our wagon train. We were all pretty tired, and the whole command, except the pickets, lay down to rest early in the evening. During the night we were disturbed by some shots fired by our sentinels at what they supposed to be prying Sioux, but nothing serious resulted. Next day we were en route very soon after sunrise, and reached our wagon train on Goose Creek in good season. The officers and men left behind were glad to see us, and Major Furey, guessing that we must feel pretty thirsty as well as hungry, did all that a hospitable warrior could be expected to do for his famished comrades. That night, after having refreshed ourselves by a bath in the limpid waters of Goose Creek, we again slept under canvas and felt comparatively happy. We learned during the night that the General had determined to send the wagon train, escorted by most of the infantry, to Fort Fetterman for supplies, and that the wounded would be sent to that post at the same time. He had sent a request for more infantry, as well as cavalry, and did not intend to do more than occasionally reconnoiter the Sioux until the reinforcements arrived. This meant tedious waiting, and Mr. McMillan, whose health had daily grown worse, was advised by the surgeons to take advantage of the movement of the train and proceed to Fetterman also. Mac, thinking there would be no more fighting, finally acquiesced, and, greatly to the regret of the whole outfit, left with the train on the morning of Wednesday, June 21st. We all turned out and gave Colonel Henry and the other wounded three hearty cheers as they moved out of camp. It was the last we were to see of them during that campaign. War-Path and Bivouac by John F. Finerty, University of Nebraska Press, Norman, OK 1961 p 82 - 98

John F. Finerty was a correspondent for the Chicago Times when he witnessed the Battle of the Rosebud. He later went on to a distinguished career in Chicago journalism, and was ultimately elected to Congress. He was a stauch stupporter of Irish independence and a hidebound rascist, as his comments about the "superior" Caucasian race indicate. Here's Lt. John Bourke's description of Finerty accidently discharging his gun while riding into the Rosebud.

|

|||||||||||