|

||||||||||||

Bruce Brown's 100 Voices... Sitting Bull's Story of the Battle

The bit about Custer laughing at the end is worth the price of admission alone, although as Sitting Bull says, he did not witness it himself. This -- and Seventh Cavalry survivor Peter Thompson's hearsay account of Billy Jackson's encounter with Custer at the beginning of the battle -- are the historical basis of the laughing lunatic Custer at the end of Thomas Berger's Little Big Man. In truth, however, the hysterical Seventh Cavalry officer in question was probably one of the other five officers wearing buckskin that day since the eye-witness record says that Custer was shot and either killed or badly wounded near the outset of the battle, as described by White Cow Bull and Pretty Shield. See Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-Witness Answer for more info. -- Bruce Brown INTERVIEW WITH SITTING BULL SITTING BULL TALKS Valuable Interview with a Herald Correspondent "I AM NO CHIEF." Graphic Description of the Rosebud Fight "HELL -- A THOUSAND DEVILS." "Bullets Were Like Humming Bees Soldiers Shook Like Aspen Leaves." CUSTER NOBLY VINDICATED "A Sheaf of Corn with All the Ears Fallen About Him." HE DIED LAUGHING An Implied Charge Against Major Reno

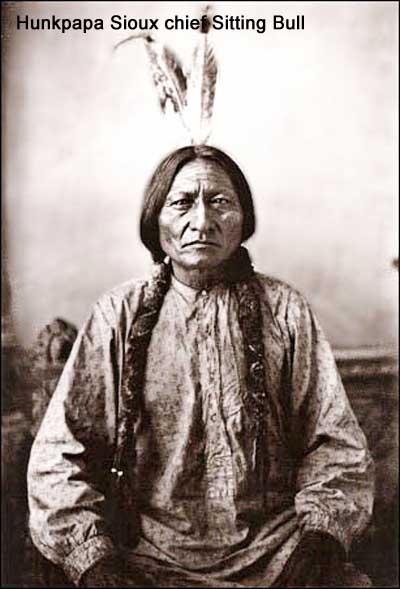

He finally agreed to come, after dark, to the quarters which had been assigned to me, on the condition that nobody should be present except himself, his interlocutor, Major Walsh, two interpreters and the stenographer I had employed for the occasion. At the appointed time, half-past eight, the lamps were lighted, and the most mysterious Indian chieftain who ever flourished in North America was ushered in by Major Walsh, who locked the door behind him. This was the first time that Sitting Bull had condescended, not merely to visit but to address a white man from the United States. During the long years of his domination he had withstood, with his bands, every attempt on the part of the United States government at a compromise of interests. He had refused all proffers, declined any treaty. He had never been beaten in a battle with United States troops: on the contrary, his warriors had been victorious over the pride of our army. Pressed hard, he had retreated, scorning the factions of his bands who accepted the terms offered them with the same bitterness with which he scorned his white enemies. Here he stood, his blanket rolled back, his head upreared, his right moccasin put forward, his right hand thrown across his chest. I arose and approached him, holding out both hands. He grasped them cordially. "How!" said he. "How!" And now let me attempt a better portrait of Sitting Bull than I was able to despatch to you at headlong haste by the telegraph. He is about five feet ten inches high. He was clad in a black and white calico shirt, black cloth leggings, and moccasins, magnificently embroidered with beads and porcupine quills. He held in his left hand a foxskin cap, its brush drooping to his feet. I turned to the interpreter and said:"Explain again to Sitting Bull that he is with a friend." The interpreter explained. "Banee!" said the chief, holding out his hand again and pressing mine. Major Walsh here said: "Sitting Bull is in the best mood now that you could possibly wish. Proceed with your questions and make them as logical as you can. I will assist you and trip you up occasionally if you are likely to irritate him." Then the dialogue went on. I give it literally. "I Am No Chief." "You are a great chief," said I to Sitting Bull, "but you live behind a cloud. Your face is dark; my people do not see it. Tell me, do you hate the Americans very much?" A gleam as of fire shot across his face. "I am no chief." This was precisely what I expected. It will dissipate at once the erroneous idea which has prevailed that Sitting Bull is either a chief or a warrior. "What are you?" "I am," said he, crossing both hands upon his chest, slightly nodding and smiling satirically, "a man." "What does he mean?" I inquired, turning to Major Walsh. "He means," responded the Major, "to keep you in ignorance of his secret if he can. His position among his bands is anomalous. His own tribes, the Uncpapas, are not all in fealty to him. Parts of nearly twenty different tribes of Sioux, besides a remnant of the Uncpapas, abide with him. So far as I have learned he rules over these fragments of tribes, which compose his camp of 2,500, including between 800 and 900 warriors, by sheer compelling force of intellect and will. I believe that he understands nothing particularly of war or military tactics, at least not enough to give him the skill or the right to command warriors in battle. He is supposed to have guided the fortunes of several battles, including the fight in which Custer fell. That supposition, as you will presently find, is partially erroneous. His word was always potent in the camp or in the field, but he has usually left to the war chiefs the duties appertaining to engagements. When the crisis came he gave his opinion, which was accepted as law." [Note: this is what made Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse (the military mujahadin) so effective when they combined forces, as they did at Arrow Creek in 1872 and at the Little Bighorn in 1876.] "What was he, then?" I inquired, continuing this momentary dialogue with Major Walsh. "Was he, is he, a mere medicine man?" "Don't for the world," replied the Major, "intimate to him, in the questions you are about to ask him, that you have derived the idea from me, or from any one, that he is a mere medicine man. He would deem that to be a profound insult. In point of fact he is a medicine man, but a far greater, more influential medicine man than any savage I have ever known. He speaks. They listen and they obey. Now let us hear what his explanation will be." A Savage Companion "You say you are no chief?" "No!" with considerable hauteur, "Are you a head soldier?" "I am nothing-neither a chief nor a soldier." "What? Nothing?" "Nothing." "What, then, makes the warriors of your camp, the great chiefs who are here along with you, look up to you so? Why do they think so much of you?" Sitting Bull's lips curled with a proud smile. "Oh, I used to be a kind of a chief, but the Americans made me go away from my father's hunting ground." "You do not love the Americans?" You should have seen this savage's lips. "I saw today that all the warriors around you clapped their hands and cried out when you spoke. What you said appeared to please them. They liked you. They seemed to think that what you said was right for them to say. If you are not a great chief, why do these men think so much of you?" At this Sitting Bull, who had in the meantime been leaning back against the wall, assumed a posture of mingled toleration and disdain. "Your people look up to men because they are rich; because they have much land, many lodges, many squaws?" "Yes." "Well, I suppose my people look up to me because I am poor. That is the difference." In this answer was concentrated all the evasiveness natural to an Indian. "What is your feeling toward the Americans now?" He did not even deign an answer. He touched his hip where his knife was. I asked the interpreter to insist on an answer. "Listen," said Sitting Bull, not changing his posture but putting his right hand out upon my knee. "I told them today what my notions were -- that I did not want to go back there. Every time that I had any difficulty with them they struck me first. I want to live in peace." "Have you an implacable enmity to the Americans? Would you live with them in peace if they allowed you to do so; or do you think that you can only obtain peace here?" "I Bought Them." "The White Mother is good." "Better than the Great Father?" "Howgh!" And then, after a pause, Sitting Bull continued: "They asked me today to give them my horses. I bought my horses, and they are mine. I bought them from men who came up the Missouri in macinaws. They do not belong to the government; neither do the rifles. The rifles are also mine. I bought them; I paid for them. Why I should give them up I do not know. I will not give them up." "Do you really think, do your people believe, that it is wise to reject the proffers that have been made to you by the United States Commissioners? Do not some of you feel as if you were destined to lose your old hunting grounds? Don't you see that you will probably have the same difficulty in Canada that you have had in the United States?" "The White Mother does not lie." "Do you expect to live here by hunting? Are there buffaloes enough? Can your people subsist on the game here?" "I don't know; I hope so." "If not, are any part of your people disposed to take up agriculture? Would any of them raise steers and go to farming?" "I don't know." "What will they do, then?" "As long as there are buffaloes that is the way we will live." "But the time will come when there will be no more buffaloes." "Those are the words of an American." "How long do you think the buffaloes will last?" Sitting Bull arose. "We know," said he, extending his right hand with an impressive gesture, "that on the other side the buffaloes will not last very long. Why? Because the country there is poisoned with blood -- a poison that kills all the buffaloes or drives them away. It is strange," he continued, with his peculiar smile, "that the Americans should complain that the Indians kill buffaloes. We kill buffaloes, as we kill other animals, for food and clothing, and to make our lodges warm. They kill buffaloes -- for what? Go through your country. See the thousands of carcasses rotting on the Plains. Your young men shoot for pleasure. All they take from dead buffalo is his tail, or his head, or his horns, perhaps, to show they have killed a buffalo. What is this? Is it robbery? You call us savages. What are they? The buffaloes have come North. We have come North to find them, and to get away from a place where people tell lies." To gain time and not to dwell importunately on a single point, I asked Sitting Bull to tell me something of his early life. In the first place, where he was born? "I was born on the Missouri River; at least I recollect that somebody told me so -- I don't know who told me or where I was told of it." "Of what tribe are you?" "I am an Uncpapa." "Of the Sioux?" "Yes; of the great Sioux Nation." "Who was your father?" "My father is dead." "Is your mother living?" "My mother lives with me in my lodge." "Great lies are told about you. White men say that you lived among them when you were young; that you went to school; that you learned to write and read from books; that you speak English; that you know how to talk French?" "It is a lie." "You are an Indian?" (Proudly) "I am a Sioux." Then, suddenly relaxing from his hauteur, Sitting Bull began to laugh. "I have heard," he said, "of some of these stories. They are all strange lies. What I am I am," and here he leaned back and resumed his attitude and expression of barbaric grandeur. "I am a man. I see. I know. I began to see when I was not yet born; when I was not in my mother's arms, but inside of my mother's belly. It was there that I began to study about my people." Here I touched Sitting Bull on the arm. "Do not interrupt him," said Major Walsh. "He is beginning to talk about his medicine." "I was," repeated Sitting Bull, "still in my mother's insides when I began to study all about my people. God (waving his hand to express a great protecting Genius) gave me the power to see out of the womb. I studied there, in the womb, about many things. I studied about the smallpox, that was killing my people -- the great sickness that was killing the women and children. I was so interested that I turned over on my side. The God Almighty must have told me at that time (and here Sitting Bull unconsciously revealed his secret) that I would be the man to be the judge of all the other Indians -- a big man, to decide for them in all their ways." "And you have since decided for them?" "I speak. It is enough." "Could not your people, whom you love so well, get on with the Americans?" "No!" "Why?" "I never taught my people to trust Americans. I have told them the truth -- that the Americans are great liars. I have never dealt with the Americans. Why should I? The land belonged to my people. I say never dealt with them-I mean I never treated with them in a way to surrender my people's rights. I traded with them, but I always gave full value for what I got. I never asked the United States government to make me presents of blankets or cloth or anything of that kind. The most I did was to ask them to send me an honest trader that I could trade with and I proposed to give him buffalo robes and elk skins and other hides in exchange for what we wanted. I told every trader who came to our camps that I did not want any favors from him that I wanted to trade with him fairly and equally, giving him full value for what I gotbut the traders wanted me to trade with them on no such terms. They wanted to give little and get much. They told me that if I did not accept what they would give me in trade they would get the government to fight me. I told them I did not want to fight." "But you fought." "At last, yes; but not until after I had tried hard to prevent a fight. At first my young men, when they began to talk bad, stole five American horses. I took the horses away from them and gave them back to the Americans. It did no good. By and by we had to fight." The Great Custer Battle Explained It was at this juncture that I began to question the great savage before me in regard to the most disastrous, most mysterious Indian battle of the century -- Custer's encounter with the Sioux on the Bighorn -- the Thermopylae of the Plains. Sitting Bull, the chief genius of his bands, has been supposed to have commanded the Sioux forces when Custer fell. That the reader may understand Sitting Bull's statements, it will be necessary for him to scan the map of the illustrious battle ground, which is herewith presented, and to read the following preliminary sketch. It should be understood, moreover, that, inasmuch as every white man with Custer perished, and no other white man, save one or two scouts, had conferred lately with Sitting Bull or any of his chiefs since the awful day, this is the first authentic story of the conflict which can possibly have appeared out of the lips of a survivor. It has the more historical value since it comes from the chief among Custer's and Reno's foes. The Indian village, consisting of camps of Cheyennes, Ogalallas, Minneconjous and Uncpapas, was nearly three miles long. The accompanying map will show its exact situation, also the routes pursued by Reno's and Custer's forces. It is seen from this map that Reno crossed the Little Bighorn, formed his first line just south of the crossing and charged. He says: "I deployed, and, with the Ree scouts on my left, charged down the valley with great ease for about two and a half miles." Reno, instead of holding the ground thus gained, retreated, being hard pressed. The map shows the timber in which he made a temporary stand, and it shows, too, his line of retreat back over the valley, and across the Little Bighorn and up the bluffs, on the summit of which he intrenched himself late in the afternoon. The map expresses the fact that Custer's march to the ford where he attempted to cross the Little Bighorn and attack the Indians in their rear was much longer than Reno's march, consequently Custer's assault was not made until after Reno's. The testimony of Sitting Bull, which I am about to give, is the more convincing and important from the very fact of the one erroneous impression he derived as to the identity of the officer in command of the forces which assailed his camp. He confounds Reno with Custer. He supposes that one and the same general crossed the Little Bighorn where Reno crossed, charged as Reno charged, retreated as Reno retreated back over the river and then pursued the line of Custer's march, attacked as Custer attacked and fell as Custer fell. "Did you know the Long Haired Chief?" I asked Sitting Bull. "No." "What! Had you never seen him?" "No. Many of the chiefs knew him." "What did they think of him?" "He was a great warrior." "Was he brave?" "He was a mighty chief." "Now, tell me. Here is something that I wish to know. Big lies are told about the fight in which the Long Haired Chief was killed. He was my friend. No one has come back to tell the truth about him, or about that fight. You were there; you know. Your chiefs know. I want to hear something that forked tongues do not tell the truth." "It is well." Here I drew forth the map of the battle field and spread it out across Sitting Bull's knees and explained to him the names and situations as represented on it, and he smiled. "We thought we were whipped," he said. "Ah! Did you think the soldiers were too many for you?" "Not at first; but by-and-by, yes. Afterwards, no." "Tell me about the battle. Where was the Indian camp first attacked?" "Here" (pointing to Reno's crossing on the map). "About what time in the day was that?" "It was some two hours past the time when the sun is in the centre of the sky." Custer Commanded. "What white chief was it who came over there against your warriors?" "The Long Hair." "Are you sure?" "But you did not see him?" "I have said that I never saw him." "Did any of the chiefs see him?" "Not here, but there," pointing to the place where Custer charged and was repulsed on the north bank of the Little Bighorn. "Why do you think it was the Long Hair who crossed first and charged you here at the right side of the map?" "A chief leads his warriors." "Was there a good fight here, on the right side of the map? Explain it to me." "It was so," said Sitting Bull, raising his hands. "I was lying in my lodge. Some young men ran into me and said: `The Long Hair is in the camp. Get up. They are firing into the camp.' I said, all right. I jumped up and stepped out of my lodge." "Where was your lodge?" "Here, with my people," answered Sitting Bull, pointing to the group of Uncpapa lodges, designated as "abandoned lodges" on the map. "So the first attack was made then, on the right side of the map, and upon the lodges of the Uncpapas?" "Yes." "Here the lodges are said to have been deserted?" "The old men, the squaws and the children were hurried away." "Toward the other end of the camp?" "Yes. Some of the Minneconjou women and children also left their lodges when the attack began." "Did you retreat at first?" "Do you mean the warriors?" "Yes, the fighting men." Mistaking Reno for Custer "Oh, we fell back, but it was not what warriors call a retreat; it was to gain time. It was the Long Hair who retreated. My people fought him here in the brush (designating the timber behind which the Indians pressed Reno) and he fell back across here (placing his finger on the line of Reno's retreat to the northern bluffs). "So you think that was the Long Hair whom your people fought in that timber and who fell back afterward to those heights?" "Of course." "What afterward occurred? Was there any heavy fighting after the retreat of the soldiers to the bluffs? " "Not then; not there." "Where, then?" "Why, down here;" and Sitting Bull indicated with his finger the place where Custer approached and touched the river. "That," said he, "was where the big fight was fought, a little later. After the Long Hair was driven back to the bluffs he took this route (tracing with his finger the line of Custer's march on the map), and went down to see if he could not beat us there." [Here the reader should pause to discern the extent of Sitting Bull's error, and to anticipate what will presently appear to be Reno's misconception or mistake. Sitting Bull, not identifying Reno in the whole of this engagement, makes it seem that it was Custer who attacked, when Reno attacked in the first place and afterward moved down to resume the assault from a new position. He thus involuntarily testified to the fact that Reno's assault was a brief, ineffectual one before his retreat to the bluffs, and that Reno, after his retreat, ceased on the bluffs from aggressive fighting.] Bull's Description of Hell "When the fight commenced here," I asked, pointing to the spot where Custer advanced beyond the Little Bighorn, "what happened?" "Hell!" "You mean, I suppose, a fierce battle?" "I mean a thousand devils." "The village was by this time thoroughly aroused? " "The squaws were like flying birds; the bullets were like humming bees." "You say that when the first attack was made, up here on the right of the map, the old men and the squaws and children ran down the valley toward the left. What did they do when this second attack came from up here toward the left?" "They ran back again to the right, here and here," answered Sitting Bull, placing his swarthy finger on the place where the words "Abandoned Lodges" are. "And where did the warriors run?" "They ran to the fight -- the big fight." "So that, in the afternoon, after the fight, on the right hand side of the map was over, and after the big fight toward the left hand side began, you say that the squaws and children all returned to the right hand side, and that the warriors, the fighting men of all the Indian camps, ran to the place where the big fight was going on?" "Yes." "Why was that? Were not some of the warriors left in front of these intrenchments on the bluffs, near the right side of the map? Did not you think it necessary -- did not your war chiefs think it necessary -- to keep some of your young men there to fight the troops who had retreated to those intrenchments?" "No." "Why?" "You have forgotten." "How?" A Charge Against Reno "You forget that only a few soldiers were left by the Long Hair on those bluffs. He took the main body of his soldiers with him to make the big fight down here on the left." "So there were no soldiers to make a fight left in the intrenchments on the right hand bluffs?" "I have spoken. It is enough. The squaws could deal with them. There were none but squaws and pappooses in front of them that afternoon." "Well then," I inquired of Sitting Bull, "Did the cavalry, who came down and made the big fight, fight?" Again Sitting Bull smiled. "They fought. Many young men are missing from our lodges. But is there an American squaw who has her husband left? Were there any Americans left to tell the story of that day? No." "How did they come on to the attack?" "I have heard that there are trees which. tremble." "Do you mean the trees with trembling leaves?" "Yes." "They call them in some parts of the western country Quaking Aspens; in the eastern part of the country they call them Silver Aspens." "Hah! A great white chief, whom I met once, spoke these words `Silver Aspens,' trees that shake; these were the Long Hair's soldiers." "You do not mean that they trembled before your people because they were afraid?" "They were brave men. They were tired. They were too tired." "How did they act? How did they behave themselves?" At this Sitting Bull again arose. I also arose from my seat, as did the other persons in the room, except the stenographer. As Good Men As Ever Fought "Your people," said Sitting Bull, extending his right hand, "were killed. I tell no lies about deadmen. These men who came with the Long Hair were as good men as ever fought. When they rode up their horses were tired and they were tired. When they got off from their horses they could not stand firmly on their feet. They swayed to and fro -- so my young men have told me -- like the limbs of cypresses in a great wind. Some of them staggered under the weight of their guns. But they began to fight at once; but by this time, as I have said, our camps were aroused, and there were plenty of warriors to meet them. They fired with needle guns. We replied with magazine guns -- repeating rifles. It was so (and here Sitting Bull illustrated by patting his palms together with the rapidity of a fusilade). Our young men rained lead across the river and drove the white braves back." "And then?" "And then, they rushed across themselves." "And then?" "And then they found that they had a good deal to do." [Note: a marvelous example of Sitting Bull's dry humor.] "Was there at that time some doubt about the issue of the battle, whether you would whip the Long Hair or not?" "There was so much doubt about it that I started down there (here again pointing to the map) to tell the squaws to pack up the lodges and get ready to move away." "You were on that expedition, then, after the big fight had fairly begun?" "Yes." "You did not personally witness the rest of the big fight? You were not engaged in it?" "No. I have heard of it from the warriors." How Custer Was Surrounded "When the great crowds of your young men crossed the river in front of the Long Hair what did they do? Did they attempt to assault him directly in his front?" "At first they did, but afterward they found it better to try and get around him. They formed themselves on all sides of him except just at his back." "How long did it take them to put themselves around his flanks?" "As long as it takes the sun to travel from here to here" (indicating some marks upon his arm with which apparently he is used to gauge the progress of the shadow of his lodge across his arm, and probably meaning half an hour. An Indian has no more definite way than this to express the lapse of time). "The trouble was with the soldiers," he continued; "they were so exhausted and their horses bothered them so much that they could not take good aim. [Note: here is an Arikara scout's account of a Seventh Cavelry trooper kicking his exhausted, downed horse. And here's straggler (and hence survivor) Peter Thompson's account of falling behind because his horse was too tired to keep up with the rest of Custer's command.] Some of their horses broke away from them and left them to stand and drop and die. When the Long Hair, the General, found that he was so outnumbered and threatened on his flanks, he took the best course he could have taken. The bugle blew. It was an order to fall back. All the men fell back fighting and dropping. They could not fire fast enough, though. But from our side it was so," said Sitting Bull, and here he clapped his hands rapidly twice a second to express with what quickness and continuance the balls flew from the Henry and Winchester rifles wielded by the Indians. "They could not stand up under such a fire," he added. "Were any military tactics shown? Did the Long Haired Chief make any disposition of his soldiers, or did it seem as though they retreated all together, helter skelter, fighting for their lives?" No Cowards on Either Side "They kept in pretty good order. Some great chief must have commanded them all the while. They would fall back across a coulee and make a fresh stand beyond on higher ground. The map is pretty nearly right. It shows where the white men stopped and fought before they were all killed. I think that is right -- down there to the left, just above the Little Bighorn. There was one part driven out there, away from the rest, and there a great many men were killed. The places marked on the map are pretty nearly the places where all were killed." "Did the whole command keep on fighting until the last?" "Every man, so far as my people could see. There were no cowards on either side." Duration of the Fight I inquired of Sitting Bull: "How long did this big fight continue?" "The sun was there," he answered, pointing to within two hours from the western horizon. "You cannot certainly depend," here observed Major Walsh, "upon Sitting Bull's or any other Indian's statement in regard to time or numbers. But his answer, indeed all his answers, exactly correspond with the replies to similar questions of my own. If you will proceed you will obtain from him in a few moments some important testimony." I went on to interrogate Sitting Bull: "This big fight, then, extended through three hours?" "Through most of the going forward of the sun." "Where was the Long Hair the most of the time?" "I have talked with my people; I cannot find one who saw the Long Hair until just before he died. He did not wear his long hair as he used to wear it. His hair was like yours," said Sitting Bull, playfully touching my forehead with his taper fingers. "It was short, but it was of the color of the grass when the frost comes." "Did you hear from your people how he died? Did he die on horseback?" "No. None of them died on horseback." "All were dismounted?" "Yes." "And Custer, the Long Hair?" The Last to Die "Well, I have understood that there were a great many brave men in that fight, and that from time to time, while it was going on, they were shot down like pigs. They could not help themselves. One by one the officers fell. I believe the Long Hair rode across once from this place down here (meaning the place where Tom Custer's and Smith's companies were killed) to this place up here (indicating the spot on the map where Custer fell), but I am not sure about this. Any way it was said that up there where the last fight took place, where the last stand was made, the Long Hair stood like a sheaf of corn with all the ears fallen around him." "Not wounded?" "No." "How many stood by him?" "A few." "When did he [Col. George A. Custer] fall?" "He killed a man when he fell. He laughed." "You mean he cried out." "No, he laughed; he had fired his last shot." "From a carbine?" "No, a pistol." "Did he stand up after he first fell?" "He rose up on his hands and tried another shot, but his pistol would not go off." "Was any one else standing up when he fell down?" "One man was kneeling; that was all. But he died before the Long Hair. All this was far up on the bluffs, far away from the Sioux encampments. I did not see it. It is told to me. But it is true." Not Scalped "The Long Hair was not scalped?" "No. My people did not want his scalp." "Why?" "I have said; he was a great chief." "Did you at any time," I persisted, "during the progress of the fight believe that your people would get the worst of it?" "At one time, as I have told you, I started down to tell the squaws to strike the lodges. I was then on my way up to the right end of the camp, where the first attack was made on us. But before I reached that end of the camp where the Minneconjou and Uncpapa squaws and children were and where some of the other squaws -- Cheyennes and Ogalallas -- had gone, I was overtaken by one of the young warriors, who had just come down from the fight. He called out to me. He said:"'No use to leave camp; every white man is killed. So I stopped and went no further. I turned back, and by and by I met the warriors returning." "But in the meantime," I asked, "Were there no warriors occupied up here at the right end of the camp? Was nobody left, except the squaws and the children and the old men, to take care of that end of the camp? Was nobody ready to defend it against the soldiers in those intrenchments up there?" "Oh," replied Sitting Bull again, "there was no need to waste warriors in that direction. There were only a few soldiers there in those intrenchments, and we knew they wouldn't dare to come out." A Hero's Death "While the big fight was going on," I asked Sitting Bull, "could the sound of the firing have been heard as far as those intrenchments on the right? " "The squaws who were gathered down in the valley of the river heard them. The guns could have been heard three miles and more." Adieu King Bull As Sitting Bull rose to go I asked him whether he had the stomach for any more battles with the Americans. He answered: "I do not want any fight." "You mean not now?" He laughed quite heartily. "No; not this winter." "Are your young braves willing to fight?" "You will see." "When?" "I cannot say." "I have not seen your people. Would I be welcome at your camp?" After gazing at the ceiling for a few moments Sitting Bull responded: "I will not be pleased. The young men would not be pleased. You came with this party (alluding to the United States Commissioners) and you can go back with them. I have said enough." With this Sitting Bull wrapped his blanket around him and, after gracefully shaking hands, strode to the door. Then he placed his fox-skin cap upon his head and I bade him adieu. The Custer Myth: A Source Book of Custerania, written and compiled by Colonel W.A. Graham, The Stackpole Co., Harrisburg, PA 1953, p 85 - 96

Sitting Bull was the single most powerful figure among the free Sioux and Cheyenne. When he learned of the Americans' unprovoked Sunday afternoon attack on June 25, 1876, his first move was to order One Bull to ride and ask for parley with the Americans. By his own word and the testimony of others like Thunder Bear, Kill Eagle and Lazy White Bull, Sitting Bull served in the roles of leader and medicine man in the battle that followed. Although he commanded his warriors in the Custer fight, he was still recuperating from the self-inflicted wounds he suffered at the Great Sun Dance on the Rosebud two weeks before, when he prophesied a great Indian victory over the American invaders. Three of his step sons fought and survived the battle: One Bull, Lazy White Bull and Little Solder. -- B.B.

|

|

|||||||||||

Fort Walsh, Northwest Territory, October 17, 1877 -- THE conference between Sitting Bull and the United States Commissioners was not, as will presently be seen, the most interesting conference of the day. Sitting Bull and his chiefs so hated the "Americans," especially the American officers, that they had nothing for them but the disdain evinced in the speeches I have reported to you. After the talk with Generals Terry and Lawrence the Indians retired to their quarters. But through the intercession of Major Walsh, Sitting Bull was persuaded at nightfall to hold a special conference with me. It was explained to him that I was not his enemy, but that I was his good friend. He was told by Major Walsh that I was a great paper chief who talked with a million tongues to all the people in the world. Said the Major: "This man is a man of wonderful medicine; he speaks and the people on this side and across the great water open their ears and hear him. He tells the truth; he does not lie. He wishes to make the world know what a great tribe is encamped here on the land owned by the White Mother. He wants it to be understood that her guests are mighty warriors. The Long Haired Chief (alluding to

Fort Walsh, Northwest Territory, October 17, 1877 -- THE conference between Sitting Bull and the United States Commissioners was not, as will presently be seen, the most interesting conference of the day. Sitting Bull and his chiefs so hated the "Americans," especially the American officers, that they had nothing for them but the disdain evinced in the speeches I have reported to you. After the talk with Generals Terry and Lawrence the Indians retired to their quarters. But through the intercession of Major Walsh, Sitting Bull was persuaded at nightfall to hold a special conference with me. It was explained to him that I was not his enemy, but that I was his good friend. He was told by Major Walsh that I was a great paper chief who talked with a million tongues to all the people in the world. Said the Major: "This man is a man of wonderful medicine; he speaks and the people on this side and across the great water open their ears and hear him. He tells the truth; he does not lie. He wishes to make the world know what a great tribe is encamped here on the land owned by the White Mother. He wants it to be understood that her guests are mighty warriors. The Long Haired Chief (alluding to